“The greatest factor in beauty is mathematical order.” This concept arose in antiquity, received a theological basis from Augustine and impacted the aesthetics of the Middle Ages before decreasing in influence during the epochs that followed. There are however, even in recent times, objects that have resulted from precisely this fundamental idea. Our example is the art of the Shakers.

Who were the Shakers?

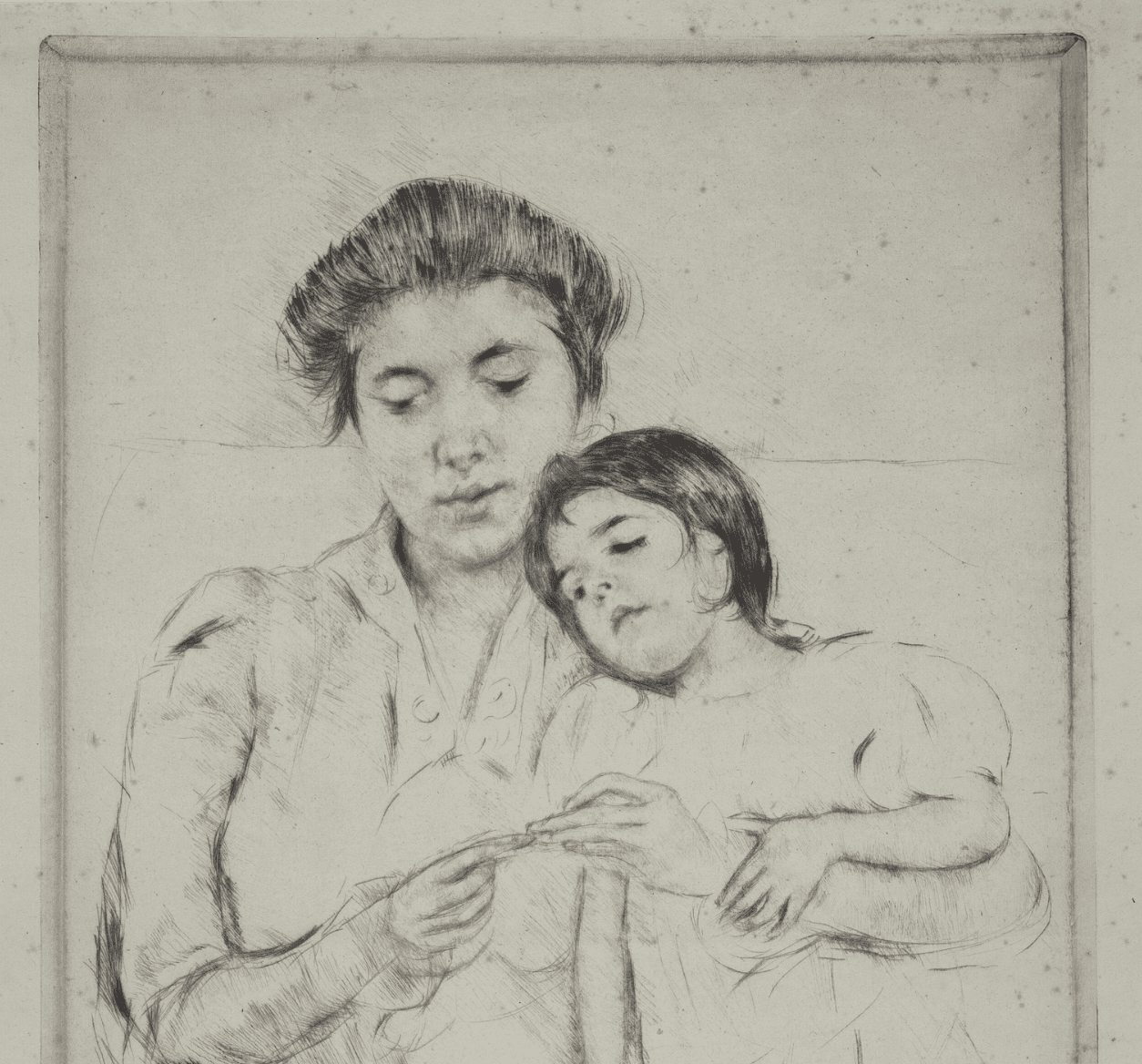

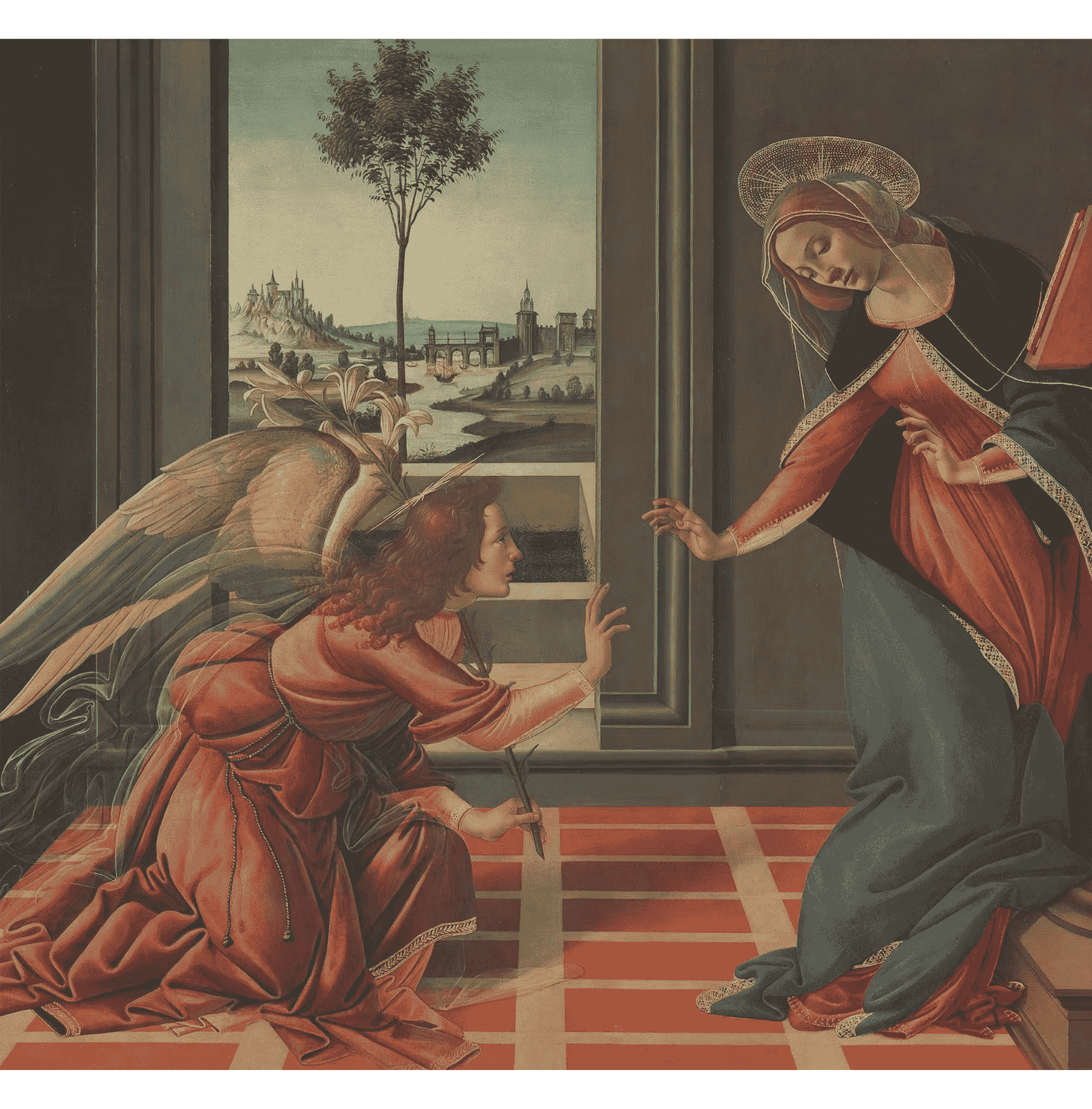

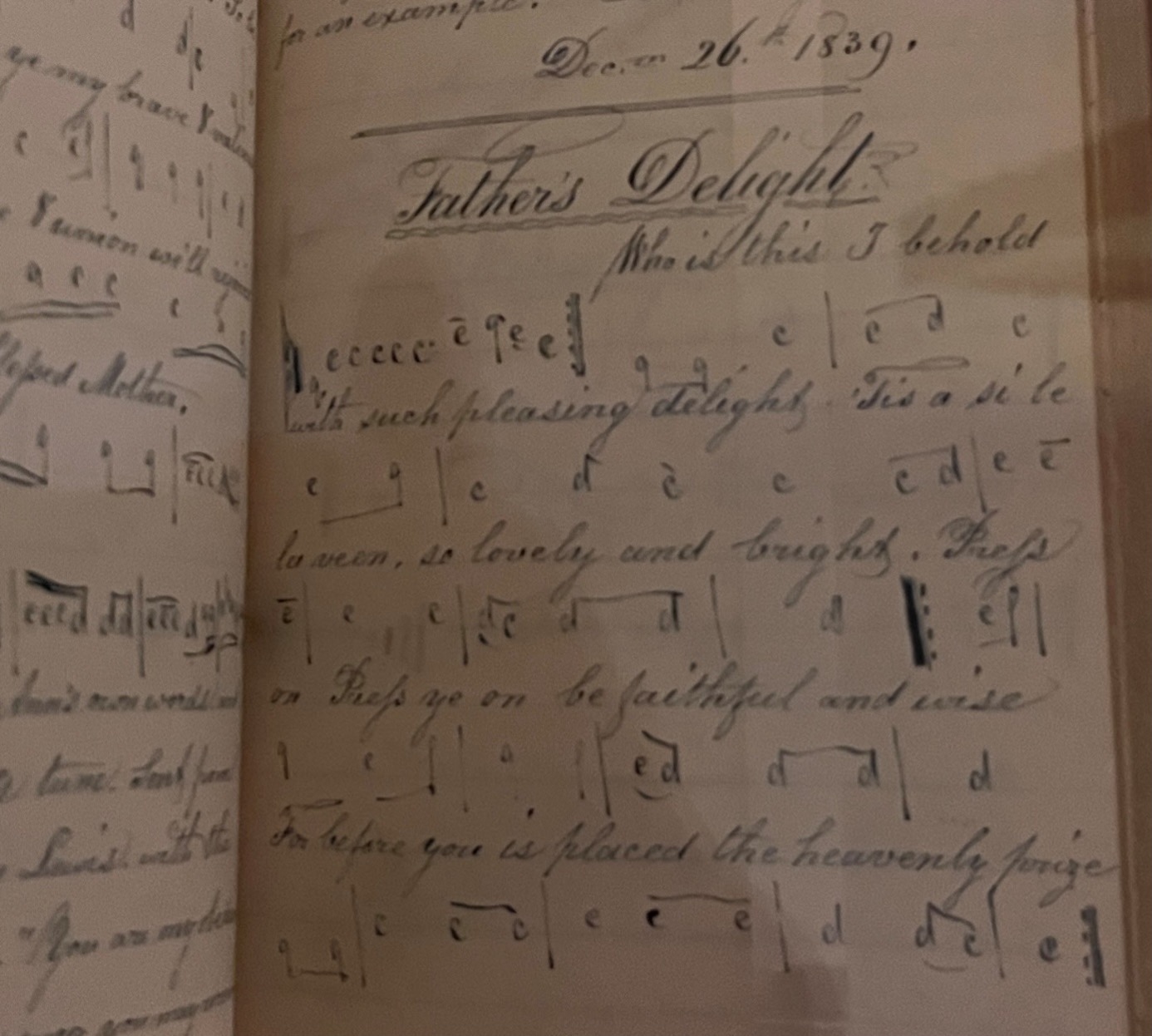

Actually, the question should be: Who are the Shakers? For in 2025 there were still at least two of them alive. After emigrating from England to America in 1774, their believers formed the “United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing” as the basis for their own settlements. Their goal was to establish a religious community based on principles of shared property, equality of sexes, pacifism, and charity. And the reason why they called themselves Shakers or “Shaking Quakers” was that in their – initially at least – ecstatic gatherings there were powerful manifestations of the Holy Spirit, including prophecy, speaking in tongues and convulsions. Leadership in the community was often in the hands of women. Through their missionary activity many people came to faith. In the course of history, the fire of revival often broke out – as in the first half of the 19th century, when numerous songs and pictures (inspired “gift drawings”) were created.

Mount Lebanon

One important settlement was Mount Lebanon, NY. The architecture which sprang up there set the style for other settlements. They followed the English colonial style, at the same time developing it further. The equal social rank of the members led to a standardisation and seriality of the buildings. The size of the community forced them to provide space by building with multiple stories. And, to make sure the community had enough space for church services and above all for liturgical dance, it was necessary to build huge meeting houses. In addition, there was a strict separation of the sexes, which required a doubling of entrances and staircases.

"It’s a gift to be simple, a gift to be pure!"

One of the community’s songs (the composer Aaron Copland and the choreograph Martha Graham drew on it in 1944 in “Appalachian Spring”) praises the simple and pure life. They had renounced the world, since the return of the Lord was imminent. This is also the reason why they lived in celibacy, although they did adopt orphaned children. Because perfect geometrical order is waiting for us in the New Jerusalem, the aesthetics of the faithful even now should be “simple and pure”. Apart from in the architecture, this is also reflected in the order of the liturgical dances and in the simplicity of the furniture and utility objects, which soon became the trademark and top-selling products of the skilful Shakers.

From broom to Scandinavian design

“There is no dirt in heaven”, stated the founder Mother Ann Lee (1736-1784). It is therefore no coincidence that the flat broom was invented by Shakers in 1798 and was soon sold throughout the world.

In 1927, the father of modern Danish design, Kaare Klint (1888-1954) discovered a Shaker chair and drew inspiration from it. Quite generally, even the Shaker objects originating from the 18th century have a very modern feel about them. One could almost speak of a “Christian aesthetic principle” which gave rise to an entire style.

Are Shaker objects, in their simplicity, of captivating beauty? Or are they (like the social life of the Shakers, so strongly determined by their imminent expectations) too puristic? Do they come across as too mathematical? Too functional? A matter of taste…

Whatever the case, we can certainly learn one thing from the Shakers: faith can become incarnate in art.

%20(1).png)