Articles

The Complete Works of Hans Rookmaaker, edited by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker (Piquant).

Vol 1: Art, Artists and Gauguin, 441 pp hdbk, ISBN 1-903689-06-6

Vol 2: New Orleans Jazz, Mahalia Jackson and the Philosophy of Art, 404 pp hdbk,

ISBN 1-903689-07-4.

Peter Smith - The Complete Works 1 and 2

The Complete Works of Hans Rookmaaker Vols 1 & 2: Review Article

by Peter S. Smith

The Complete Works of Hans Rookmaaker, edited by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker (Piquant).

Vol 1: Art, Artists and Gauguin, 441 pp hdbk, ISBN 1-903689-06-6

Vol 2: New Orleans Jazz, Mahalia Jackson and the Philosophy of Art, 404 pp hdbk,

ISBN 1-903689-07-4.

I have known about the plan to publish H R Rookmaaker’s complete works for some time. Over the years I have read what I could find in English but knew there was a wealth of material in Dutch. We now have the first two volumes in print with the next two to follow soon. Any anxieties one might have had about ‘raised hopes being dashed’ have been dispelled. When I started to read I could ‘hear’ the familiar voice from the lectures in the text. I was immediately reminded of tapes I had made of four of Rookmaaker’s lectures. They took place over a weekend in December 1974 at the old ACG headquarters off Kensington High Street. I had finished my formal education in 1970, and then returned to Birmingham where I had studied Fine Art. A weekend in London to hear Rookmaaker, meet old friends, exchange ideas and news and see some galleries was one of the gifts ACG had to offer non-Londoners. As I listen to the tapes the incidental sounds bring it to life. The faint sound of carol singers in the High Street, the muffled noises of a good friend’s daughter, just beginning to crawl, bumping into the mike. Some of us had just moved from the student world into the world of work and our own families. At the end of the tape the clear youthful voices of ACG members can be heard asking questions. Those who remain are now older than Rookmaaker was at his death.

So much for a glimpse of ACG history and nostalgia. The publication of these works has nothing to do with nostalgia. I once heard Rookmaaker say something like, ‘When we stop talking about Rubens, Rubens dies.’ Since his death there has been constant talk, in certain circles, about Rookmaaker and his work. For those people he is certainly still ‘alive’. These volumes are bound to increase that circle and continue the conversation.

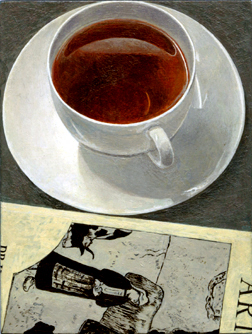

Peter Smith: Black Tea: for Hans Rookmaaker, 1977

It is no secret that, like many others, I came across Rookmaaker at a crucial time in my life. The list of those who are still active in the fields of the arts in the broadest sense, let alone other disciplines, and would admit to some kind of debt to Rookmaaker is too long for this review. Rookmaaker’s biblical and reformational thinking about the arts re-located many of us in a fuller and richer world with the freedom and responsibility to serve Christ beyond the confines of pietism. Even those who found themselves disagreeing still had to think about the relationship between the arts and faith. Whether you think you know Rookmaaker well or are new to his work, these volumes will hold fascinating surprises for you.

Dr Graham Birtwistle, Associate Professor of Art History at the Free University Amsterdam, has written an excellent introduction: ‘H. R. Rookmaaker: the shaping of his thought’. In the mid 1960s, at the start of his own art-historical career in England, Birtwistle met Rookmaaker and many of the art students who attended Rookmaaker’s lectures. He then moved to Amsterdam to study under Rookmaaker at the Free University and to teach Art History there. This combination of an Englishman, immersed in Dutch culture and art history, while working very closely with Rookmaaker, places him in an ideal position to write as he does. Dr Birtwistle is now a respected art historian in his own right with published research giving new insights into his specialist areas of Primitivism in twentieth-century art, and especially the Cobra movement. His introduction really helps us to contextualise these collected works. It is no hagiography but a truthful and honest account of the development of Rookmaaker’s thinking. It is especially clear as it places him in the post-war years (1945 onwards) with some pertinent observations about his contribution to Christian thinking.

Birtwistle helps us to understand what Rookmaaker faced as he wrote these various pieces. He prevents us from reading back into history, so making it possible for us to see what is of lasting and current value. In 1949, when Rookmaaker was 27 years old, he reviewed a Cobra exhibition of experimental art at the Stedelijk Museum. Karel Appel, the Cobra painter, whose work was in the exhibition, was 28 years old. We have the interesting situation of two young men who have both recently experienced the devastation of World War Two. On the one hand, the artists are proposing a revolutionary future and would do away with all those values which would seem to have contributed to the recent horrors. On the other, the art critic wants the same things but knows, from his Christian perspective, that this kind of revolution and destruction of all norms is no solution either. Birtwistle quotes a passage from Rookmaaker’s review which contains this critique of Cobra: ‘Experimentalism is the most consistent kind of nihilism … Civilisation, conventions, norms, morality, beauty, these are obsolete concepts to be rid of.’ (i 341-2). Rookmaaker adds, The (psycho-somatic) life, which houses the true inner self, must express itself directly, unrestrained and unfettered by the detestable mind. Well, when we hear talk like that, we know well where it will end. He then exhorts his reader not to mock these works or dismiss them but take them seriously. Birtwistle adds that as a result of his own researches into Cobra he ‘cannot agree that this was a nihilistic movement without norms and values’. He goes on: ‘Of course, it is one thing to write about Cobra at a safe distance of several decades and quite another to have faced these developments when they were new and provocative’ (i xxii). Rookmaaker viewed scholarship as an on going discussion aimed at truthfulness not certainty. I heard him say that he looked forward to the day when his books would be replaced by newer, better ones. He would have approved of the continued appraisal of Cobra by Dr Birtwistle and would, no doubt, have enjoyed discussing it until the early hours.

The content of the six volumes has been arranged part chronologically and part thematically. This seems to work well, especially where shorter works of a later date fit better in the context of a theme instead of being stuck on their own in strict date order. The first two volumes include material from before 1960 – in other words, prior to the mid-1960s to 1970s, by which time Rookmaaker was well known as a popular speaker. I was a student in the late 1960. The major Rookmaaker work we had in English was his doctoral thesis on Gauguin and his circle, Synthetist Art Theories. This is the central work in volume one. The book has been re-proof-read with all the artists’ quotes in English. In the original version most of these quotes were in the artist’s own language. This new version makes for easier reading for those not fluent in French.

My own copy of the original book falls open at the section, ‘The Iconic - the real achievement of synthetist art theory.’ This, as much as Rookmaaker’s lectures, really influenced my own student painting. Rookmaaker’s deep interest in the renewal of visual language in the twentieth century pointed to an optimistic way forward and a way to deal with the visual experience of the world free from the limitations of nineteenth-century Realism/Naturalism. As a student it is always easier if the world is starkly black and white in every way. I knew Rookmaaker was critical of Cubism, and in one student conversation I was dismissive of them myself, trying to reinforce my own prejudice. His response was to tell me to go and try it out – ‘Cubism is only a visual language, after all.’ I learned a good lesson. One might have serious questions about the underlying philosophy of some works but it is a mistake to think it all negative. The new visual language may well have possibilities in another context.

This first volume ends with Rookmaaker’s art criticism for the Dutch daily newspaper Trouw between 1949 and 1956, all translated from Dutch for the first time. They were written as he was studying and, no doubt, sometimes in haste to meet deadlines. They give us a good idea of the range of his interest and the kinds of works he was looking at. It was around this time that he met Francis Schaeffer. By the time I heard Rookmaaker again, in 1968, he was speaking alongside Schaeffer at a L’Abri conference at Ashburnham Place in southern England. I did find Schaeffer really helpful at the time but it would be true to say that, as a visual artist, I had more ‘faith’ in Rookmaaker’s opinions. Schaeffer tended to go for the very broad brushstrokes while Rookmaaker, because of his specialist interest, kept things more open. There is a passage in one of Rookmaaker’s exhibition reviews that makes an interesting comparison with a similar passage in Schaeffer’s The God Who is There and makes the difference in approach clear. Schaeffer refers to a ‘De Stijl’ exhibition he has seen at the Stedelijk Museum in 1951. In describing Mondrian’s attempt to build a universal truth in his painting he suggests that, because the paintings conflict with the room, a new room had to be built with new furniture to return the space to the balance Mondrian required. However, he concludes that it fails because, ‘If a man came into the room there would be no place for him. It is a room for abstract balance, but not for man.’

I think we know what Schaeffer trying to say, especially since much of the International architectural style has a dehumanising aspect, but listen to Rookmaaker’s review of the same exhibition: For this movement [De Stijl], whether we concur with its theories and slogans or not, provided healthy ideas in the realm of style and art, particularly where people applied these to architecture, furniture and the applied arts. And indeed, with the work of architects like Oud and Reitveld proceeding in close contact with the work of painters of this movement, a new art and style arose that had a profound and wholesome influence on our architecture and interiors in general. (i 319)

Central to volume two is another book, first published in 1960, Jazz, Blues and Spirituals, also now in English for the first time. Rookmaaker’s interest in jazz goes back to his own boyhood before the Second World War. Birtwistle points out that there was a time when Rookmaaker might have followed a career in musicology rather than art history. My own musical education is limited to popular music and some jazz with great gaps elsewhere. I found Rookmaaker’s account, with its friendly chronological story and unabated enthusiasm for this music, very informative. Behind it can also be found a great empathy for the trials of Black Americans and a desire to get their contribution to music down in print. Some of the obituaries written at the time of Rookmaaker’s death were penned by jazz enthusiasts who knew Rookmaaker through his music writing rather than his art history.

The articles about music that accompany Jazz, Blues and Spirituals are full of the same enthusiasm. Writing from New York in 1961, he says, ‘Len [Kunstadt] made sure that I was introduced to everyone and so, a few hours after seeing the Manhattan skyline for the first time, there I was among musicians.’ He describes his meeting with Lonnie Johnson, guitarist and singer from the 1930s: ‘These sorts of encounters are curious. Up till then Lonnie had been to me a sort of mythical figure that could be heard on a number of rare recordings from a colourful though very distant past. And then, suddenly, one is standing to the very man, chatting away.’ (ii 356)

I rarely heard Rookmaaker speak of his links with the Dutch Christian philosophical group that included Dooyeweerd and Vollenhoven, although I did know there was a strong connection. In discussion, in 1974, I heard him say something like, ‘Read Dooyeweerd but then throw it away – it’s not the Bible.’ While he was happy to use these ideas he was wary of any system which people were tempted to place above a direct encounter with the Bible.

This brings us to the final collection in volume two: Rookmaaker’s articles from this period on philosophy and aesthetics. Perhaps one of the most interesting and maybe difficult ones was written when he was 24 years old and called, ‘Sketch for an Aesthetic Theory based on the Philosophy of the Cosmonomic Idea.’ Birtwistle explains that this was early Rookmaaker exploring these ideas and establishing his Dooyeweerdian credentials. It is also a demonstration of how he applied what he had learned to his own specialism. However he chose not to write in quite this way again, preferring to see these ideas translated into ‘ordinary’ language. This desire to be understood, because these matters of art are so vital, was to characterise the rest of Rookmaaker’s work. Nevertheless there are glimpses of the later Rookmaaker.

Some of this work is historical in interest. Most of it is more than that. If we think of the cave paintings at Lascaux as a long time ago, then Rembrandt was last month and Rookmaaker yesterday. This is the same culture we are immersed in. He still talks about our culture. The ACG asked me to mentor some young artists. I still hear the same questions being asked. Parts of the institutional church still want to control the visual arts, whether it be pinning them down in a ‘theology’ of the arts or shackling them to narrow views of ‘worship and evangelism’. Some are still confused about inspiration. Others still try to baptise pseudo-spiritual gnostic ideas with their rejection of the created world. Many of the old familiar problems survive alongside the new ones.

Finally, how do we come to have these volumes in our hands? I have always thought that it would be a good idea to collect these works together; but if left to people like me it would remain just ‘a good idea’. This project has involved a great deal of hard work and commitment. The Church and wider circles too will forever be in debt to Rookmaaker’s daughter, Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker, along with her team of translators and helpers, for making this possible. To me this is as much an act of love as it is scholarship. The work of Pieter and Elria Kwant at Piquant have ensured that it is presented in an attractive and well designed form. I know that this has not been a simple commercial venture for them but equally an act of great generosity. While the set is not expensive for what it is, it is still a large investment for most individuals. One can only hope that it sells well in institutions around the world. Every library should have one. Any Christian interested in the arts should make every effort to get a sight of this.

Peter S Smith is retired Head of School: Art, Design and Media at Kingston College. He is a Further Education representative on the Council of the National Society for Education in Art and Design (NSEAD). Last year he joined the Board of the European Academy of Culture and the Arts as UK representative. The Academy is an initiative of the CNV-Kunstenbond in the Netherlands. In 1974, at Rookmaaker’s invitation, Peter organised an exhibition at the Free University of Amsterdam of young artists Rookmaaker had befriended while visiting Birmingham School of Art and Design in 1968. Peter Smith’s Black Tea: for Hans Rookmaaker was exhibited in the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1977, the year of Rookmaaker’s death.

Review of Hengelaar-Rookmaaker (ed.): H.R. Rookmaaker: The Complete Works volume 1 and 2, Piquant – Carlisle in ARTSMEDIA JOURNAL 3 (2002).