Maritain, Rouault, Chagall, Arcabas - D. Jeffrey

Jacques and Raïssa Maritain among the Artists

by David Lyle Jeffrey

In a time of intense nihilistic impulses and a general loss of a sense of meaning in culture, it is tempting to think that artists must inevitably reflect if not herald the abandonment of future hope. Certainly the early twentieth century in France offers many instances of avant-garde figures who descended into abject nihilism. Such was the state of mind of many intellectuals who did commit suicide in this period, as well as of others like Jacques (1882-1973) and Raïssa Maritain (1883-1960) who made a joint suicide pact and stepped back only because at the last minute they recovered faith in transcendent Being.

The Maritains were friends of important artists and Jacques Maritain’s essays were an influence on others who eventually bucked the trend. With varying degrees of personal suffering and sacrifice, yet a persistent will to choose for life, George Rouault, Marc Chagall, and Jean-Pierre Mirot, better known as Arcabas, also looked into the dark abyss, rejected it, and then resolved to look beyond the ashes of exhausted modernism. Respectively, each were drawn toward an existential affirmation of transcendental truth; each therefore became a religious artist in a modern yet paradoxically also traditional sense, using their exceptional artistic gifts to acknowledge the True (Rouault), the Good (Chagall), and the Beautiful (Arcabas) as ultimate realities, bearing within them the gifts of life and future hope.

Having long ceased to be Christo-centric, French art in the first decades of the twentieth century now rejected homo-centricity. Picasso’s cubism is only one of many artistic expressions of the loss of humanist confidence. For Jacques Maritain, an intimate of artists as well as philosophers, the consequences were obvious: “If there is no man, there is no artist: in devouring the human, art has destroyed itself.” The eager participation of the Surrealists, from Breton to Dali, in “devouring the human” had proved to be self-destructive. The obverse of Breton’s sociopathic Surrealist act – wandering into a crowd and firing a revolver at random as long as possible – is a form of self-annihilation.

Georges Rouault

Georges Rouault (1871-1958), a lapsed Protestant, had a religious conversion in 1904, apparently as a result of reading the Bible. This experience seems to have produced a sudden insight followed by maturing contemplation over a period of several months. He said,

When I was about thirty, I felt a stroke of lightning, or of grace, depending on one’s perspective. The face of the world changed for me. I saw everything I had seen before, but in a different form and a different harmony.

From his conversion through the next decade Rouault strove to paint the human person, but with spiritual rather than corporeal realism, eschewing what most obviously appears to the eye, especially in any form of flattering light or perspective, in order to evoke the actual emotional state of his subjects. At the same time he became a friend of the Maritains, especially Jacques, and their conversations enriched Maritain’s thinking about art-making as a virtue.

Maritain was among the first to see that Rouault’s empathy with the emotional suffering of his contemporaries was the key to his abandoning of his earlier mode of “realism” and his post-conversion choice to make his art evocative rather of inward truth: “What he sees and knows with a strange pity,” says Maritain, “is the miserable affliction and lamentable meanness of our times, not just the affliction of the body, but the affliction of the soul, the bestiality and self-disguised vainglory of the rich and the worldly, the crushing reality of the poor, the frailty of us all.”

To be empathetic means literally to “suffer with,” to identify with the sorrows and even sins of others. For Maritain Rouault’s Miserere series of 58 black and white engravings (1917-27), many of which are re-workings of his paintings, were a kind of summary expression of the artist’s concern for inward and ultimate truth. Rouault actually gave Maritain a complete set of the etchings and their friendship, according to Raïssa Maritain, significantly influenced Maritain’s Art and Scholasticism (1920). The question at bottom for both artist and philosopher is as old as Plato: in what sense is art able to give us Truth?

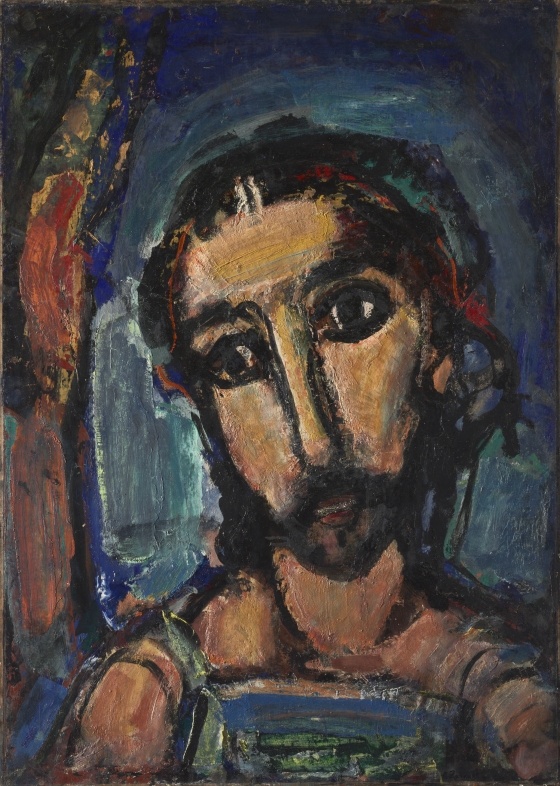

Rouault’s specifically religious paintings, a major group of which he produced in the 1930s, are on a continuum with his early paintings and his etchings for his Miserere. It is the Passion of Christ, his vicarious suffering, which dominated this period. Rouault’s Christ is preeminently the Suffering Servant announced in Isaiah: “Wounded for our transgressions and bruised for our iniquities.” Nor is it by accident that the Miserere series ends with the Veronica image of Christ’s face bearing the words, “It is by his wounds that we are healed” (Isa. 53:5) (Plate 58). His images of Christ, inflected by quotations from Isaiah, the gospels and St. Paul (e.g. Phil. 2:8), emphasize God’s identification with human suffering. They are executed in the manner of his earlier work – heavy outlines as if the units of an image were separated by the leaded glass of a cathedral window – but with a tenderness that elevates the corporeal, and a radiance that sometimes lights the whole composition yet seems to come through the image from behind, as in stained glass painting.

[Fig. 1. Rouault, Head of Christ, oil on paper, pasted on canvas, 41 ¾” x 29 ½”, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1937]

The intellectual collaboration of Rouault and Maritain helps answer to the question, “What is Christian art?” Maritain answers in his Art and Scholasticism: it is the “art of humanity redeemed,” a theme that strongly linked Fra Angelico and George Rouault in the philosopher’s mind. Foregrounding the human in a spiritual way led Rouault naturally back to iconic Christocentric images, painting which is not merely religious but iconic. He was fascinated with the vera-icon, the “true icon” of Christ, associated in Christian tradition with Veronica and the image impressed upon a cloth she is said to have used to wipe away his bloody sweat en route to Golgotha. This legendary incident, kept in Christian memory through the Franciscan-inspired “Stations of the Cross,” is explicitly recalled in Rouault’s image of Veronica herself (1945) and a representation of her imprinted cloth, The Holy Countenance, produced the following year.

A Christian icon represents not so much historical reality as present and eternal metaphysical Reality. Maritain gets at this when he says Rouault’s painting “clings… to the secret substance of visible reality” in such a way that its “realism” refers to the “spiritual significance of what exists (and moves, and suffers, and loves, and kills).” These are the qualities that for Maritain make Rouault’s work transformative, not in the sense that all his darkness (so essential to his truthfulness) gives way in the end to light, but transformative in that the ordinary truths of existence, our own and those experienced by Jesus, are allowed to find their ultimate meaning in transcendent Truth.

Marc Chagall

The Maritains were friends also to the Jewish painter, Marc Chagall (1887-1985), though Raïssa, herself born in a Hasidic community in the same area as Chagall, was here the chief agent of the couple’s influence. That members of the Hasidic Jewish community were, as Raïssa Maritain puts it, inclined largely to ignore the secular world and to be “bathed each day in the living waters of the Scriptures” is well known; that the range of their response to Scripture extended into the arts has received less attention than it deserves.

As a refugee in Paris Chagall was attuned to nihilistic revolutionary ideas in their European context, yet his friendship with the Maritains, as Raïssa’s book about him suggests, may have given him sufficient antibodies to the virus that his own exuberant joyfulness and gratitude was unhindered. They encouraged and influenced his reading of the New Testament. As one of his own poems in Yiddish (1938) suggests, his artistic identification with Jesus’ passion was by then to some degree becoming personal:

I carry my cross every day,

I am led by the hand and driven on,

Night darkens around me.

Have you abandoned me, my God? Why?

Chagall’s biblical knowledge is here revealed as a knowledge of both Hebrew (Ps. 22) and Christian Scriptures (Luke 9:23), and the force of the combined allusions suggests that for Chagall Jesus was an example he felt called in some way to follow as an artist.

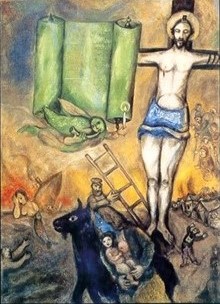

[Fig. 2. Chagall, The Yellow Crucifixion, oil on canvas, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, 1943]

While like Chagall, Raïssa Maritain was raised in a Polish-Lithuanian Hasidic community, unlike him, she converted to Christianity – at the same time as her husband, Jacques (1906). Her newly embraced Catholic perspective may possibly be thought to have over-determined her relationship with Chagall, but that she retained a close friendship with him through her life suggests otherwise. As a Jewish convert she had informed sympathies extending to both traditions, and her account of the theological element in their conversation is instructive. In her Marc Chagall ou l’orage enchanté (Genève et Paris: Éditions des Trois Collines, 1948), a slight expansion of the first edition with more illustrations of works by Chagall as well as some of Chagall’s poems and some of her own, she comments that The White Crucifixion (1938) radiates a terrible beauty distinctive in Chagall’s oeuvre. It seems likely, as she suggests in her comments on the crucifixion-motif paintings that anticipate it, that the use of the ladder motif in these paintings alludes less to Jacob’s ladder than it reflects traditional Christian renderings of the Descent from the Cross. Yellow Crucifixion (1943) is another reclamation of the Jewishness of Jesus, a recognition of the continuity and confluence of Jewish and Christian history. We may reasonably imagine that, like Rouault, Chagall’s keen awareness in the Suffering Servant as portrayed by Isaiah (Isa. 52:13-53) could be understood to apply to both the Jews collectively and to Jesus representatively. The claim of Raïssa Maritain in this regard, namely that Chagall is “un artiste selon Isaie” is entirely justified. All the evil in the world notwithstanding Chagall proclaims the enduring Good.

Arcabas

Jean-Marie Pirot, aka Arcabas (1926-2018), was born into a nominal Catholic family. Like Rouault he experienced an adult conversion. As with Rouault something decisive happened when he began reading the Bible. “Faith fell upon me like a bucket of water,” he later reported. He became more than a casual reader:

I am a Bible and New Testament enthusiast. I bury myself in it many times per week. I have an ancient edition of Luther’s vernacular Bible, written in the gothic style. I also have a Chouraqui version of the Bible, which takes extraordinary shortcuts due to its direct translation from the Hebrew, as well as the Jerusalem Bible. Whenever I have a painting to paint, I draw from these Bibles the paragraph that inspires me…. I read a passage and am engrossed. It is an awe-inspiring book. One understands [in this way] how 2000 years later it still appears as a remarkable novelty. When I read the Bible, it seems like it all happened just yesterday, so much is its text present in my spirit.

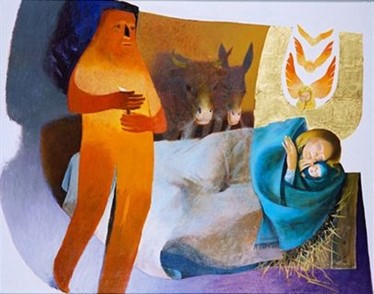

Arcabas is an unusually literate painter. His remarks reveal familiarity not only with the Bible (Luke’s gospel is his primary text), but with classic works of Christian spirituality such as Augustine’s Confessions, the novels of Georges Bernanos, many of the philosophical essays of Jacques Maritain, and the encyclicals of Pope John Paul II. Although the influence of Maritain is entirely through his writings, especially those about art, Arcabas counts as another artist on whom the philosopher’s thought has worked for good. In an interview with theologian Christophe Batailh he spoke of the obligation of a Christian artist who recognizes in himself a calling to “speak the truth, reflect the goodness of things, and the beauty of the face of God.” Clearly he agreed with Maritain, that “the moment one touches a transcendental, one touches Being itself, a likeness of God, an absolute, that which ennobles and delights our life; one enters in[to] the domain of the Spirit.”

[Fig. 3. Arcabas, La Nativité, oil on jute, Archepiscopal Palace, Malines, Brussels, 2002]

While for each of these artists a direct and intensive reading of the Bible was central to the formation of their spirituality and hence their imagery, each was influenced by Jacques Maritain’s philosophy of art, and Rouault and Chagall even more directly by personal friendship with the Maritains. All three created art for places of worship, each designed stained glass windows for reverential space, each returned to the human person that meaning which comes from being made imago dei, made in the image of God—a central emphasis in the writing and conversation chez Maritain. Their collaboration returned to modern French art the beauty of the human face.

****

David Lyle Jeffrey is Distinguished Professor of Literature and the Humanities at Baylor University and Guest Professor of Peking University. His most recent publications have featured the painting of Marc Chagall and Ding Fang, and his book In the Beauty of Holiness: Art and the Bible in Western Culture (Eerdmans) came out in 2017.