Between the Shadow & the Light - R. Hostetter

Winter Flowers

Lessons from South Africa Between the Shadow & the Light

by Rachel Hostetter Smith

Winter Flowers ZA by Joseph Cory

It is January—winter in my part of the world. The earth is frozen, covered with a thick blanket of white, the temperature has dropped to well below zero, and those who are able remain safely ensconced in their homes just out of reach of the elements that threaten to consume us. The pines bow deeply under the weight of the snow that rests heavily on their outstretched branches, those green boughs the one small sign of life in an otherwise inhospitable landscape.

It seems fitting that in the northern hemisphere Christ’s birth came to be celebrated in conjunction with the Winter Solstice when pagan Romans celebrated the “birth of the unconquered Sun” to mark the start of Spring as the light slowly began to increase little by little each day. With the appropriation of this holiday for the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ, Christians also adopted and adapted some of the symbols like evergreens to serve as a reminder of the new life that lay dormant unseen until the time was right for it to burst into full flower.

In a very real sense, there are seasons of life that are like winter when we hunker down in a defensive posture unable to do more than just weather the storm and hope to survive. From a theological perspective, we live in a world, as was literally the case in C. S. Lewis’ Narnia, that is in a state of perpetual winter where warm sunshine and the verdant life it nurtures is such a distant memory that it has been relegated to the realm of myth by all but a faithful few.

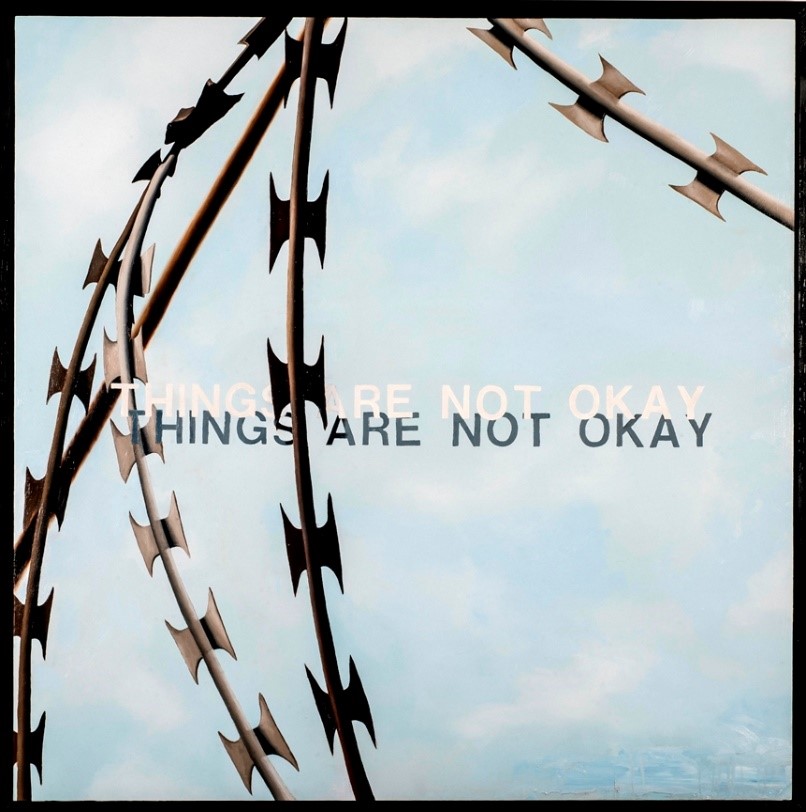

Barriers Still by Larry Thompson

“Things are not Okay”

In June 2013, a group of twenty North American and African artists from six African countries met in South Africa for two weeks of intensive engagement with South Africa—its’ unsettling and frequently disturbing history, its’ vibrant mix of cultures, and its’ increasingly tenuous contemporary situation. But in actuality, the point of their gathering was not really to learn about South Africa but to learn from her. We recognized that the issues encountered in South Africa have application everywhere and that South African art signaled fresh ways of addressing the complex realities of the past, the present, and hope for the future, particularly for people of Christian faith. The works this group of artists produced in response to their experience became the traveling exhibit, Between the Shadow & the Light: An Exhibition Out of South Africa.

Despite the tremendous advances South Africa has made toward achieving Nelson Mandela’s vision of a rainbow nation—a remarkable constitution, a level of healing for some individuals and society, open elections, freedom of movement and economic opportunities that did not exist for the majority only a couple of decades ago—problems remain and new challenges threaten the health of the democracy and the well-being of the people and the state. Limited educational resources for a growing population, the devastation of a whole generation and certain populations by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, unemployment estimated to be between 30 and 50 percent, and corruption undermine the efficacy of nearly every aspect of society and government. As Johan Horn, Executive Head of ALICT (African Leadership Institute for Community Transformation) has said, “Things are not okay.”

Larry Thompson’s provocative painting Barriers Still has Johan’s words emblazoned on a bright blue sky, as arcs of razor wire slice across it, destroying the apparent tranquility. The razor wire proffers both protection and threat, a barrier designed “to keep something in and keep something out” as Larry explains. Johan was right. Things are far from okay—in South Africa, or anywhere else. The evidence is everywhere we look.

Constructing Hope by Magdel van Rooyen

“Colour the Wind”

Some years ago, in the former township of Gugulethu on the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa, the J. L. Zwane Church established a program called “Colour the Wind.” In essence, the church will paint a room in the home of someone in the community who is dealing with some sort of loss, hardship or distress. The residents choose the color—any color. When asked why the church didn’t just paint the entire house, the program organizers said the objective of “colouring the wind” was to incite a fresh breeze to blow through the household by interjecting a small but nevertheless tangible change. They didn’t paint the entire house because they knew that the existential change they sought to inspire required the residents to take up the responsibility for carrying that change throughout the rest of the house. If a mere change of the color of the walls of one’s house can inspire hope and the will to act, what more might works of art be able to do? Our world is in a continuous cycle of decay and construction where forces of every kind act to break down the infrastructures that sustain our lives and very being.

South African artist Magdel van Rooyen captures this reality in her work Constructing Hope in profound ways. On a piece of warped salvaged metal, she paints a road with a ribbon of concrete construction barriers and bright orange plastic safety fencing snaking around an intersection making it all but impassable. As with Gustave Courbet’s monumental painting Burial at Ornans (1849), the viewer stands at the edge of a dark hole that drops away in the foreground. Broken chunks of asphalt and dislocated stones threaten to tumble into the abyss. Constructing Hope presents us with the sometimes overwhelming piles of rubble that need to be cleared away before restoration or something new can be built in its place, and the necessity of holding firm to the hope that it will one day be made new again.

Beauty’s Vineyard by Kimberly Vrudny

“Winter Flowers”

When it is summer in the northern hemisphere, it is winter in South Africa, just as some of us enjoy seasons of peace and well-being while others experience the depths of distress and destruction. The national flower of South Africa is the protea. Protea is a genus of flower indigenous to South Africa. It is among the oldest families of flowers on earth. They are winter flowers that bloom when the rest of nature lies dormant. Like the evergreen, the protea is a visible reminder of the new life that is coming as the earth warms and the seeds that have been planted germinate and begin to grow. It takes its name from Proteus, the son of the Greek god Poseidon, who had the power to know all things past, present and future, and could change his shape at will. With more than 1400 varieties, the protea embodies great diversity and a multiplicity of possibilities within a single genus, symbolizing the possibility, however latent, for human and societal flourishing in South Africa and the whole world that just requires cultivation.

Kimberly Vrudny’s work Beauty’s Vineyard reminds us that restoration and renewal depend on addressing the evil that ensues all around us. The title, Beauty’s Vineyard, suggests the nature of the task. A vineyard requires careful tending: selection and preparation of the soil, planting of the root stock, grafting and pruning, monitoring the weather to adjust for slight shifts in temperature or rain. Perhaps most essential of all, a vineyard requires watching and waiting patiently as the vines grow before they bear fruit and the grapes can be pressed to make wine. A single disaster could seem to undo it—heavy rains that cause mold, drought, fire or an unexpected freeze. It is an arduous undertaking; the threats innumerable.

As American artist Joseph Cory writes about his series of drawings titled Winter Flowers ZA, “I liked the metaphor of a flower that blooms in the winter, typically experienced as a time of death and germination in the colder climate of North America.” The phrases scrawled on several of the works are drawn from encounters in South Africa: “Sometimes you have to carry and sometimes you have to be carried” (Dumile Feni on his sculpture History), “We have made a road by walking” (Zenzile Khoisan in his poem Fare Thee Well), and “the struggle continues,” a phrase encountered everywhere.

Working to bring about a better world is no different. It takes hard work and resilience. It takes faith and hope seen in the vibrant protea flower situated at the center of Beauty’s Vineyard as a sign of the new world that God is bringing into being. We may be living in winter, but spring is surely on its way. The signs are everywhere.

Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,” for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away… I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” Revelation 21: 1-5 (New International Version)

*******

1. Winter Flowers ZA by Joseph Cory, 2013, oil pastel, india ink and acrylic on paper, each 11” x 15”.

2. Barriers Still by Larry Thompson, 2013, oil on wood, 48" x 48" (50" x 50" framed).

3. Constructing Hope by Magdel van Rooyen, 2013, oil on metal plate, 54” x 31 1/2” x 1 2/3”.

4. Beauty’s Vineyard by Kimberly Vrudny, 2013, construction of photographs printed on aluminum, 16 ½” x 16 ½”.

Joseph Cory is Associate Professor of art at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. Prior to joining the faculty at Samford in 2014, he taught art and served as chair of the Art Department at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois. He received his M.F.A. from the University of Chicago, and a B.F.A. from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He is the recipient of numerous grants and awards and has participated in a variety of competitive workshops. His artwork has been exhibited widely and he is currently working on a project on the theme of immigration.

Magdel van Rooyen is based in Pretoria, South Africa. She completed her Masters in Fine Arts at the University of Pretoria in 2012. Van Rooyen is a part time lecturer at the University of Pretoria since 2007. Her curated exhibitions include 168 Hours, 2013, and Eyetunes, 2014 exhibited during Aardklop Arts Festival. In 2012 van Rooyen was selected to take part in the Art-St-Urban residency with sculptor and entrepreneur Heinz Aeschlimann based in Switzerland. Van Rooyen is currently owner of Blokhuiz Studio Collective, a studio where she produces her own art as well as teaching painting and drawing.

Larry Thompson serves as Professor and Associate Dean of Art and Design at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama. Prior to his tenure at Samford Thompson taught in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. A native of El Paso, Texas, Larry received his B.F.A. in art and design from the University of Texas at San Antonio, and his M.F.A. in painting from the University of North Texas. Larry’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. His recent work, The Infanttree Project, was partially funded through a grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation.

Kimberly Vrudny is Associate Professor of systematic theology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. She is the author or editor of several works in theology and the arts including Beauty's Vineyard: A Theological Aesthetic of Anguish and Anticipation, and is the senior editor of the journal, ARTS: The Arts in Religious and Theological Studies. Her photography exhibit 30 Years/30 Lives: Documenting a Pandemic commemorates the lives of thirty people around the world affected by HIV/AIDS.

Rachel Hostetter Smith is Gilkison Distinguished Professor of Art History at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana. Her work has been published in many books and journals including Explorations in Renaissance Culture, Christian Scholar’s Review, Image, and ARTS. Smith is a founding member of the Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art (ASCHA). She was Curator and Project Director of the international exhibition projects Charis: Boundary Crossings, and Between the Shadow & the Light: An Exhibition Out of South Africa. She is currently working on another project in China.