Spackman, Betty: A Profound Weakness

Book Review

Betty Spackman: A Profound Weakness. Christians and Kitsch, Piquant Editions – Carlisle, 2005.

by William Collen

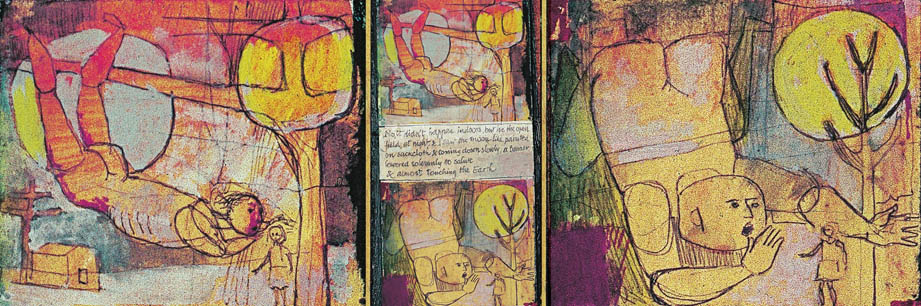

Betty Spackman’s 2005 book A Profound Weakness: Christians and Kitsch is a remarkable study of the breadth and scope of physical artifacts of contemporary Christianity. Spackman has a keen eye, noting the nuances and inflections of meaning present in even the most trivial figurines and ephemera of religious expression, and her analysis is stringent while also being extremely humble and charitable—she obviously cares for the artists who make this art, and she never forgets the human side, the motivations which undergird the art she criticizes. Her book is also lavishly illustrated with her own projects as well as with examples of found art and objects from her collection; it is a feast for the eyes, as well as a splendidly rigorous work of Christian art criticism.

Her thesis is that Christians need to be aware of what they are doing when they make physical manifestations of their faith. Because these physical manifestations are imagistic, they are open to interpretation; can we be sure that these interpretations are in accord with revealed truth? There is a serious danger here; as she puts it, “The meanings of religious symbols shift over time and in different contexts, and have to be constantly restated and renewed to maintain their impact and significance.” If we become used to seeing a particular religious symbol, we might become desensitized to the reality that symbol represents. If we see pictures of the empty tomb enough times, we might forget the utter strangeness of the resurrection.

What is kitsch, anyway? It is a very hard category to pin down, in part because any definition is so value-loaded. It strikes at the heart of the dichotomy between high and low culture. Sometimes it seems like “kitsch” is just the label art critics use to talk about a cultural attitude towards images that they themselves didn’t think up. Kitsch bleeds into folk art, naïve art, and sentimental or disposable art in ways that the cultural elites have a hard time accepting as valuable or good.

The kitsch that Betty Spackman talks about, however, is of a different kind. When she considers the visual and corporeal productions of modern, consumer-culture Christianity, she sees honest attempts by the average believer to come to terms with their faith—sometimes with questionable or suboptimal results. She says (in somewhat purple prose) that “When Mercy appears, to teach us to be still and know the Silence so that we can learn the Song, we cover the Face (too wonderful to look upon) with the materials we have stored in the chambers of our imagery.” We feel a terrifying awe in the presence of God, so we try to bowdlerize and de-mystify that experience by creating visual and tactile substitutes for that encounter. Of course, this endeavor will always fail; something will always be lost in the attempt to convey religious truth through our limited creaturely means. “Why is such profound meaning visualized in such feeble ways?” she asks.

Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that, sometimes, coming close to the presence is too much. “Such knowledge is too wonderful for me” declares king David (Psalm 139:6). It can be overwhelming; we would much rather have a tamer and more approachable version of the faith. Perhaps also, the answer lies in people’s need for immediate religious experience. Maybe these things are important to people precisely because they are so easily apprehended. I’ve heard people say that going to the Rothko Chapel is a profoundly moving religious experience, but they also say they had to stare at Mark Rothko’s black paintings for hours to get the effect. What if I need spiritual solace right now? Can’t I just look at a cheap plastic crucifix or read a sentimental poem?

Is it good to have such emotional reactions to art? What is the difference between an appropriate response to art, and a rudderless sentimentality? James Elkins wrote a whole book about instances where paintings have incited viewers to come to tears. Much of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot centers around emotional reactions to Hans Holbein’s painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb; when Dostoevsky himself viewed the painting in Dresden, his wife had to drag him away from it lest he fall into an epileptic fit. He later said that a person could lose their faith from looking at it.

But surely it can’t be true that exaggerated emotion is always kitsch. We ought to involve our emotions in worship—an attitude of intellectual detachment isn’t particularly healthy. Besides, the history of art is full of works which portray strong emotion. No one dismisses Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, the angels in Giotto’s Lamentation, or Picasso’s The Weeping Woman by calling them kitschy. What, then, is the difference?

When Thomas Kinkade described his paintings as an attempt “to portray a world without the fall,” and then proceeded to paint everything as if it were set in the English Cotswolds, the problem seems to be that his Anglocentric vision of paradise is expected to be normative. Who are we to say that paradise will have anything at all in common with one particular historico-spacial concept of what the good life should be? Similarly, Betty Spackman discusses a “Peace on Earth” greeting card with a very prominently displayed American flag on it. Why did the makers of this card equate American the political entity with global peace?

This is the real danger of kitsch—it short-circuits our critical faculties and tells us a lie about what to believe. Remember, images aren’t propositions, but they really want you to believe they are. In the face of lying images, we must be careful what we find ourselves believing.

In the book’s preface James Romaine states that “Faith yearns to find form.” But should it? It seems to me that if faith requires physical object to focus on, then it is no longer faith. “Faith is the evidence of things not seen” says the apostle (Hebrews 11:1); what becomes of faith if it can be seen? Do we still keep our faith in the truths of scripture, or have we substituted a faith in the symbols of our religion?

Yet there is a place for physical objects in the service of faith. Churches are physical objects; the sacrament of communion is a very material reality; the words of scripture are met by us as words printed on a physical page or displayed on a physical screen. How these are decorated is certainly significant. Spackman relates this story:

An artist approached me after a lecture I had given. In a near whisper, she “confessed”: “I used to use a lot of religious kitsch in my work. One of the objects was a glow-in-the-dark praying hands with the words ‘Remember to Pray’ on it. I used to keep it in my bedroom and of course when I turned the lights off I . . . Well, I . . .”

She hesitated and blushed.

“You’d pray?” I asked.

“Yes!” she exclaimed in an embarrassed voice.

And really, who has a right to argue with that? If a piece of religious art—even a cheap and ugly plastic trinket—can push us closer to the God who is of infinite and inestimable value, is there anything wrong with that?

This is the tightrope that Spackman walks in A Profound Weakness, and she is always aware of the danger of falling off either side into a denunciation of all sentimentalized religious art, or an unthinking embrace of the same. Her approach is also one of great humility in the face of the authentic expressions of religious feeling she sees in much art labeled kitsch by the cognoscenti; she is unwilling to take a stance of “throw all this cheap stuff out” because it obviously fills such an important need among the people who make it. A Profound Weakness is a record of one artist’s extended exploration of that need, and she clearly and cogently details her thoughts along the way. Reading her book is like bouncing ideas off a good friend; there are many places where her observations caused me to stop and reflect on my own beliefs and opinions about the use of religious art. I would recommend her book to anyone who struggles with these ideas in their own life.

***

William Collen is an art writer and researcher from Omaha, Nebraska, USA. His writings can be found at www.ruins.blog.

Betty Spackman is a Canadian multimedia installation artist and painter with a background in theatre, animation, performance art and video art. She has exhibited internationally and taught studio art at various universities and community arts programs for over 20 years. She has written, illustrated and published art related books and has collaborated, taught and spoken at conferences and galleries in Canada, Europe, the US and Mexico. A Profound Weakness: Christians and Kitsch, Spackman’s 500p illustrated book published in 2005 by Piquant Editions, UK is a personal journal and commentary about images of faith in popular culture. Spackman is also a mentor and community arts educator and has developed The Open Studio Program, an alternative community education model for emerging artists used in Yellowknife, NWT, Medicine Hat, AB, and Langley, BC. Her work has focused on cultural objects and the stories connected to them with a more recent focus on issues of animal/human relations. FOUND WANTING, a Multimedia Installation Regarding Grief and Gratitude (2010-2014) was a 3000 square feet installation project built around a large collection of animal bones and addressed issues of the killing and commodification of animals. Her most recent book and installation project is A Creature Chronicle. Considering Creation: Faith and Fable, Fact and Fiction (2019/2020).