Taylor + Worley ed: Contemporary Art + the Church

BOOK REVIEW

W. David O. Taylor and Taylor Worley (ed.), Contemporary Art and The Church: A Conversation Between Two Worlds. Westmont, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2017.

by William Collen

Is religion the enemy of contemporary art? It certainly seems so sometimes—witness the uproar from religious spaces that happens over artworks such as Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ. Contemporary artists are stereotypically seen as only interested in the provocative, the transgressive, and even the offensive—and the church doesn’t want any of that sort of thing, right? Christians are supposed to be interested in moral behavior and objective truth; how does that pursuit coexist with artists’ search for subjective and unfettered self-expression?

Contemporary Art and The Church: A Conversation Between Two Worlds makes the case that there is, in fact, common ground between these two seemingly opposed ideologies. Twenty-two writers and thinkers contribute to this book; the editors, W. David O. Taylor and Taylor Worley, are members of Christians In The Visual Arts, a group that, since 1979, has been trying to serve the needs of both artists and Christians, and especially Christian artists, as they navigate the sometimes fraught space that lies between these camps.

It’s important to remember that the two worlds of contemporary art and the church have some very important similarities. Both deal in the transcendent, interpreting reality in a way that might not be readily noticed, and providing new ways of seeing the world. The church is a place of worship, a surrendering of one’s self to God; art demands a similar surrender (yet, perhaps, one that is not so comprehensive). For many Christians, artistic treatments of religious themes enable them to more fully comprehend and emotionally engage with the teachings of scripture; for many artists, religious ideas give their art a philosophical and ideological center. Even the sometimes bizarre activities and theatrics that contemporary artists often engage in have a scriptural antecedent; in the book’s first chapter Wayne Roosa points out that the prophet Isaiah, who was commanded by God to walk around naked for three years to highlight the Egyptian people’s imminent punishment, has a counterpart in artists such as Yayoi Kusama, whose troupe of dancers performed naked in front of the New York Stock Exchange to protest the Vietnam war. These similarities give the book’s contributors hope that a meaningful and mutually worthwhile relationship can be achieved between the art world and the church.

The church could serve the cause of contemporary artists in a very significant way, argues Jonathan A. Anderson in his chapter. He identifies a key omission in the current critical discourse surrounding the contemporary art scene: established critics are giving very little acknowledgement to the religious themes which frequently pop up in current artists’ work. Anderson cites a long list of artists from the past half-century whose work deals with theological concepts; one, who he doesn’t mention, and who comes to my mind right away, is Damien Hirst. His by-now-infamous The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living serves to remind me that death is real, and we all must come to terms with that reality, even if it doesn’t seem to be real to us who are alive—an idea which can be found all over the Bible.

Damien Hirst’s notorious stuffed shark. It’s not scary anymore when it’s stuffed and under glass, and death isn’t scary when we aren’t thinking about it.

Thinkers from the church have something to say to Hirst, and Hirst has something to say to religion, in this sculpture. But the world of contemporary art criticism doesn’t often discuss this sort of thing, Anderson asserts. He goes on to say that the church has the necessary resources to engage deeply with the theological concerns of some contemporary artists, but that these resources are almost always hidden away in seminaries, being used to conduct the church’s ongoing and very detailed discussion of the Bible. But if some of these resources are not also used to engage with artists, it will be hard for a conversation between art and the church to continue.

Conversely, art can serve the church by showing the church that art does not have to only be didactic. Ben Quash points out that art speaks many dialects, and so does the church—but church art is commonly only “trying to lecture an apostate world on the way things really are and what to do about it.” If the church would let its art speak in the subjunctive (“what if?”), interrogative (“why?”), or optative (“if only . . .”) moods, instead of only the indicative (“this is”) or imperative (“you must”), the church might grow and enrich its ability to communicate through visual means.

But maybe the two sides are, in fact, in opposition? This idea is the elephant in the room, that the book’s authors would rather not have to acknowledge. But Katie Kresser, in her chapter “Contemporary Art and Corporate Worship”, has this to say:

Early modern theorists like Tristan Tzara and Viktor Shklovsky strove with all their might, sinew, and bone against social impulses that would bring us the World Wars and the Holocaust. According to Tzara, the best way to destroy the groupthink that led to these atrocities was to “destroy the drawers of the brain”, to shock the senses, to “defamiliarize” a perversely organized reality, and to assert one’s inimitable individuality in the face of regimes that enforced conformity. The church, conversely, could be accused of perpetuating a kind of groupthink. in its effort to make everyone feel welcomed and loved, it certainly didn’t indulge in shock tactics. Needless to say, in a paradigm of heroic individualism and politically savvy transgressiveness, the church was a natural enemy.

Kresser raises a good point. If artists like Tristan Tzara (one of the founders of Dada, perhaps the art movement that most fully embraced the pursuit of the irrational and bizarre) have a prior commitment to an agenda of anti-collectivist thinking and radical self-expression, what common ground do they have with organized Christian religion, whose followers are committed to conforming in all ways possible with the life and work of Jesus Christ? This dilemma seems irreconcilable. If we choose to follow Jesus, we by definition can’t follow our own heart. What is to be done?

It seems to me that the unspoken problem is that the church is unwilling to concede anything to the contemporary art world; at the same time, the contemporary art world has a lot to lose if it allies itself with the church. The relationship is rather lopsided, and I don’t know of any way around that.

Of course, it’s important to remember the distinction between Christians and the church. Perhaps some aspects of contemporary art are, indeed, not appropriate in the space of corporate, public, formal worship. This might be where the difficulty lies: artists might be feeling pushback from the church, and interpreting it as pushback from Christians. But the church has a very specific and circumscribed role to play in society, and contemporary art sometimes simply does not assist in that role. The problem is defined very succinctly by Wayne Roosa in the book’s first chapter:

Art and church are different spheres with different roles, even though they intersect profoundly. I want my church to be a community of faith, worship, and service. I want it to respect and value art, but I do not want it to be an art community. Its constituencies and jobs are too diverse. In turn, I want my art community to respect and value the spiritual and theological, but I do not want it to be a surrogate church or a worship of aesthetics.

In other words, the church does not want to be colonized by the arts, and the arts do not want to be colonized by the church. This is legitimate. Perhaps, though, there needs to be a dedicated, involved group of Christian art lovers who are willing to take the effort to learn from and dialogue with the contemporary art world, and to pass on what they have learned to the Christian community at large. Kresser calls these people “cultural diplomats”, and the title is very fitting: a Christian cultural diplomat would represent the art world to their fellow religionists, and encourage them to explore and get involved as they themselves have done.

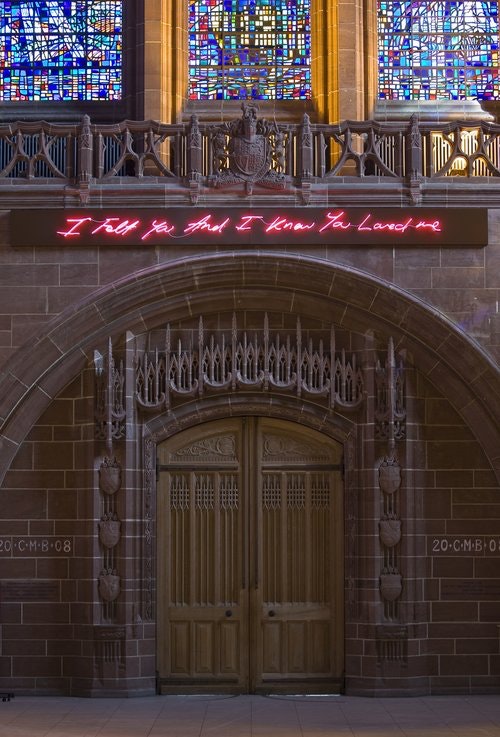

This tension, this holding together of two very different yet complementary spheres of human activity, can be extremely difficult to achieve. But Contemporary Art and The Church is written in the hope that the balancing act can be accomplished successfully. It will take hard work, to be sure, and broken relationships will have to be mended, and trust will have to be built. Ben Quash’s chapter “Can Contemporary Art Be Devotional Art?” details some instances of this, the most surprising certainly being how Tracey Emin (!) was commissioned to furnish a piece for the Liverpool Anglican Cathedral’s west doorway.

Tracey Emin, For You. 2008

If even someone like Emin can find acceptance for her work in an ecclesiastical setting, and if the church is comfortable giving her a space for her work, anything is possible. Contemporary Art and the Church is written in that spirit, that anything is possible if these two worlds take the time and effort to learn from and relate to each other. Of course such an undertaking will be difficult. But the book’s authors are willing to do that work.

***

William Collen is an art writer and researcher from Omaha, Nebraska. His writings can be found at www.ruins.blog