Joy and Heartache

Luke is the only gospel writer to give particular attention to the ‘visitation’, when Mary visits Elizabeth before their babies are born. In his diligent research (Luke 1:3), presumably mostly carried out during the two years he spent in Palestine while Paul was in prison (Acts 24:27), he will have had opportunities for conversation with Mary about Jesus’ early history. This episode must have struck him as significant.

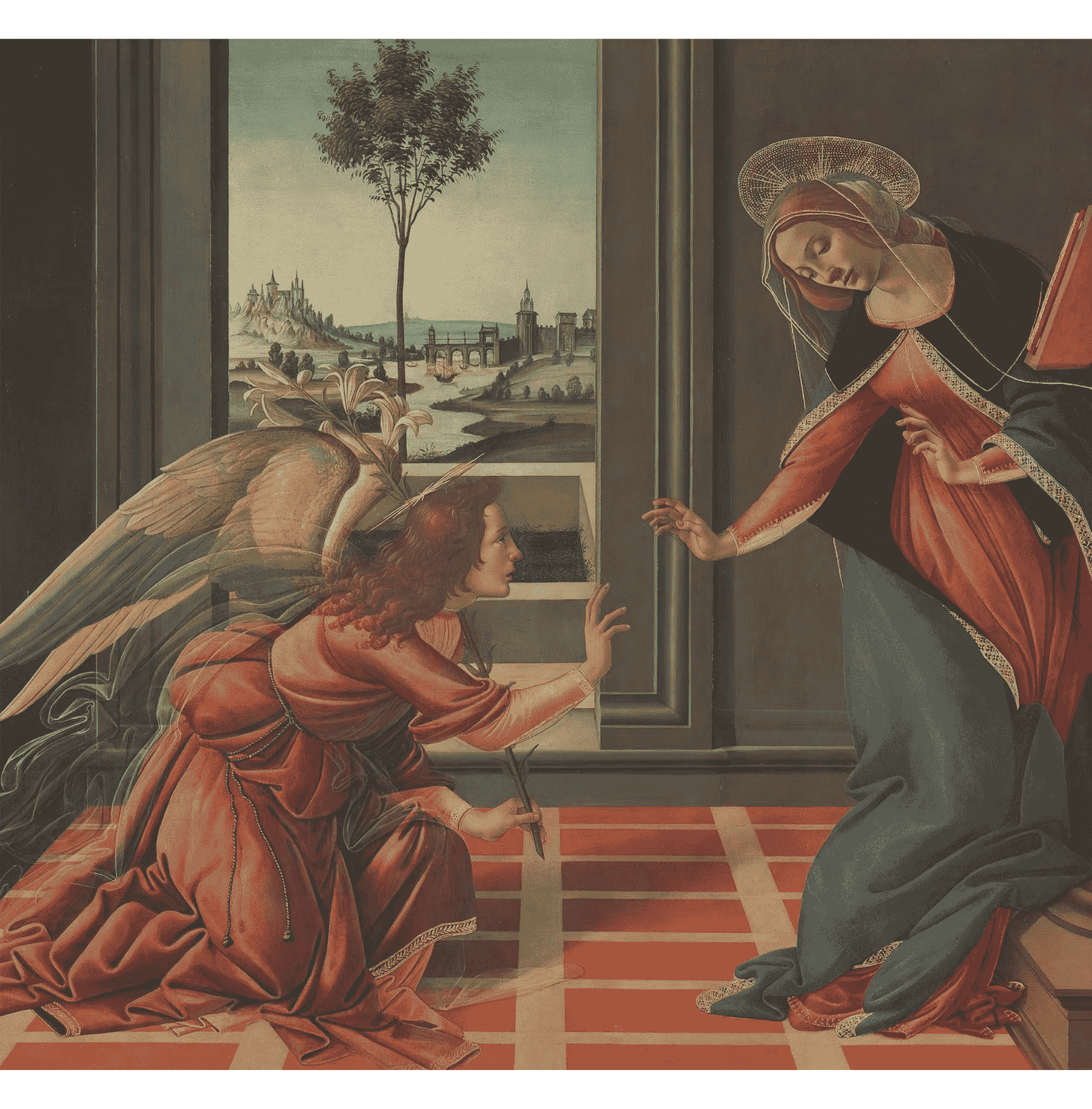

The incident is the first public recognition of Jesus, when John the Baptist – whose job it is to witness to Jesus as the Messiah (Luke 1:17; John 1:8, 29) – responds to Jesus even while in the womb. Pontormo is perhaps suggesting this by making the two ‘bumps’ bump. Luke wants his readers to ‘know the certainty’ of the gospel and here, right at the start, we see the evidence accumulating that Jesus really is the Messiah.

Pontormo’s imagining of this scene is both fascinating and disturbing. He is one of the first of the so-called ‘mannerist’ painters, a term of abuse applied by later generations who saw the strangeness of his works – and those of Rosso, Tintoretto, Parmigianino and others – with their distorted perspective, bright colours and unusual compositional forms. They were seen as works painted merely in the ‘manner’ of the Renaissance, but not very well.

However, the Mannerists’ distortion of Renaissance space and harmony was undoubtedly deliberate. It is suggested that it reflects the dramatic political upheavals of the period, from the schism of Christendom at the Reformation to the traumatic sack of Rome in 1527 by German peasant soldiers, followed two years later by a terrible siege of Florence, which ended with their short-lived republic being overthrown by the Medicis.

Pontormo’s Visitation is painted in Florence just before or during the siege. John the Baptist is the patron saint of Florence and perhaps the painting is a pious call for help. But the sense of strangeness is everywhere. The figures fill the frame in a quadrilateral form. The action is all in the top third. The centre of the picture is empty – except, hidden away, unpainted, Jesus is actually in the middle! The perspective is confusing: compare the steep slope on the left, leading to the tiny figures in the distance, with the steps on the right, leading presumably into the home of Elizabeth and Zechariah.

Unlike Renaissance images of the Visitation which always showed Elizabeth bowing to Mary in keeping with her exalted status in Roman-Catholic theology, Pontormo, reflecting a widespread sympathy for Lutheranism in republican Florence, shows the encounter as a greeting of equals. See how tenderly they take hold of each other and how sympathetically Elizabeth looks into Mary’s eyes. Elizabeth, in her pregnancy, has been given what she had always wanted, a son, and had been freed from her feeling of disgrace (Luke 1:25). Mary, however, has been given a child she did not ask for and faces a future coloured with disgrace in the eyes of her family and villagers for conceiving outside wedlock. Both are caught up in God’s plans, which brings both joy and heartache. You get the feeling that Elizabeth feels great sympathy for Mary for the road that lies ahead. Mary seems to return her gaze with quiet determination.

And yet it is unimaginably exciting too: God is clearly on the move. Mary has been told that she will give birth to the Messiah. Elizabeth and Zechariah know their child will be the one to announce the new Messiah. And as signs that God is on the move Elizabeth has miraculously been able to conceive despite her advanced years and Mary has miraculously been able to conceive while still a virgin.

But what is really disconcerting in the painting is the deadpan stare of the two women in the background. In the age of the Renaissance it would be improper for a woman of good character to be unaccompanied in the street. So, as the Visitation is staged outside the house, the presence of companions was normal. However, these two figures seem to be the alter-egos of the two main characters. The figure on the left looks like Mary, has the same red hair, and is wearing the same colours, but in inverse proportions. The older woman in the background has the same facial features as Elizabeth, wears an identical head-covering, but seems slightly younger, less wrinkled.

Quite what role these figures play has never been determined, but Pontormo obviously wanted us to take them seriously. They stare straight out at us, as is common with many Mannerist paintings. They bring a gravity and engagement to the scene, refusing to let the viewer be a neutral, disinterested spectator. At the very least they ask us: ‘What do you think? What is going on here? What does it mean for the world, for you?’

If we see them as alter-egos, they might in the spirit of Lectio Divina invite us to enter imaginatively into the inner experience of Mary and Elizabeth. How do they feel, two ordinary women caught up in momentous events beyond their control? How would you feel if you were caught up in God’s plans?

And by the way, you are!

**********

Jacopo Pontormo: The Visitation, 1528-30, oil on panel; 202 × 156 cm; Propositura dei Santi Michele e Francesco, Carmignano, near Florence)

Jacopo Pontormo (born Jacopo Carucci, 1494–1557) was among the earliest exponents of Italian Mannerism. Influenced by Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea del Sarto, he worked for the Medici, Borgherini and other patrons of Renaissance art in Florence, making his initial reputation with fresco works at the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano. Like other Mannerist artists Pontormo's compositional design took precedence over naturalism and perspective. Thus, where High Renaissance painters sought harmony, Pontormo looked for drama and special effect. His angular style of cinquecento draughtsmanship owed a great deal to works by Michelangelo and Albrecht Dürer, although his sense of colour was entirely his own. Pontormo is famous for two outstanding works: The Deposition (1526-8), painted for the altarpiece of S. Felicita and a cycle of frescoes in the Church of S. Lorenzo (1546-56).

Nigel Halliday is a freelance teacher and writer in the history of art and a Bible teacher at Hope Church in Greatham and Petersfield, in the UK. See www.nigelhalliday.org.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 15 December 2019

%20(1).png)