J Romaine ed: Christ in African American Art

Book Review: Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art, ed. James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill

by Victoria Emily Jones

Typically when scholars interpret African American art, they do so through the primary lens of racial identity, often glossing over overt Christian themes, expressions of religious identity. Beholding Christ and Christianity in African American Art (Penn State University, 2017), edited by James Romaine and Phoebe Wolfskill, seeks to redress that dearth by examining the Christian content, including theological significance, of works by fourteen African American artists who came to maturity between the Civil War and the civil rights era: Mary Edmonia Lewis, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Aaron Douglas, Malvin Gray Johnson, Archibald Motley Jr., William H. Johnson, James Richmond Barthé, Allan Rohan Crite, Sister Gertrude Morgan, William Edmondson, Horace Pippin, James VanDerZee, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence. Many of these artists were themselves devout Christians, working out of internalized religious convictions and not merely outward tradition or market expectations.

The essayists certainly take race into account as a factor in the works discussed, but not the only factor; political, socioeconomic, and biographical circumstances are also considered. Christianity, however, as the title suggests, is given pride of place in the selection and examination of the fifty-five images reproduced in the book.

One of the hallmarks of Beholding Christ is the diversity of styles, media, and denominational affiliations represented. As the book shows, African American art is no monolith, and neither is African American Christianity. While there is so-called primitive art and visionary art created by self-taught individuals with crayons, cardboard, or salvaged limestone, there is also neo-classical sculpture, as well as other academically informed works that tend toward impressionism or expressionism. Among the pages are rough-hewn stone sculptures, abstract watercolors, naturalistic oil paintings, and portrait photographs. While there are many depictions of Christ as black, there are also, per tradition, white Christs, and even a Middle Eastern one. What was most surprising to me was to see examples of art by African Americans from high-church traditions, like Catholicism and Anglicanism, who distinguish themselves from low-church Baptists, Pentecostals, and Holiness Christians. The editors are to the applauded for resisting the urge to perpetuate a narrow vision of “Negro art” in line with what the artists’ contemporary critics and viewers principally sought.

Another hallmark of the book is the rigorous formal evaluation and content analysis of specific artworks that make up the bulk of almost every essay, encouraging readers to look deeply. Biographical information about the artists is well integrated and does not overwhelm the focus on the works themselves. Given this image-forward approach, I must say, I’m disappointed that a handful of works, for which color photographs should be available, are reproduced in black and white—for example, Motley’s Tongues (Holy Rollers), Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom, and Lawrence’s Sermon II and Sermon VII. Luckily these can be found online, but as the entire book is printed in full color with glossy pages, I wonder why color photographs of these were not sought or obtained.

Lastly, I really appreciate the connections between artists made possible by the bringing together of these essays—some made explicitly by the authors, others implied. Douglas and Lawrence both dignified the art of black preaching by visualizing sermons. Crite and Johnson visualized the spirituals, but used very different approaches. Edmondson and Morgan were both motivated by a belief that they were divinely ordained to create by supernatural visions. Episcopal Crite and Catholic Motley intertwined class and religion in their works.

This book is essential reading for anyone in the fields of Christianity and the arts or African American studies. As one belonging to the former category, I see these artworks as part of not only art history but Christian history, and as worthy of being studied by Christians as any theological treatise, written scripture commentary, saint’s biography, or church trend. These artworks teach theology; they encapsulate hopes and fears; they comment on public issues; they expose sin; they lead us in celebration and in lament; they help us to remember the works of Christ, and invite us into communion with him; they tell us who we are and from whence we’ve come; they cast a biblically grounded vision for the future.

What follows is a brief summary of each chapter.

In chapter 1, Kirsten Pai Buick traces the network of patronage that supported Catholic sculptor Mary Edmonia Lewis, as well as the multiple geographic moves she made to further her career: from Boston to Rome (1865), Rome to Paris (1893), and Paris to London (1901). Because many of Lewis’s religious works have been lost, little attention is given in this chapter to the art itself; the only art illustration is her conventional-looking Bust of Christ (1870), mentioned cursorily in the text.

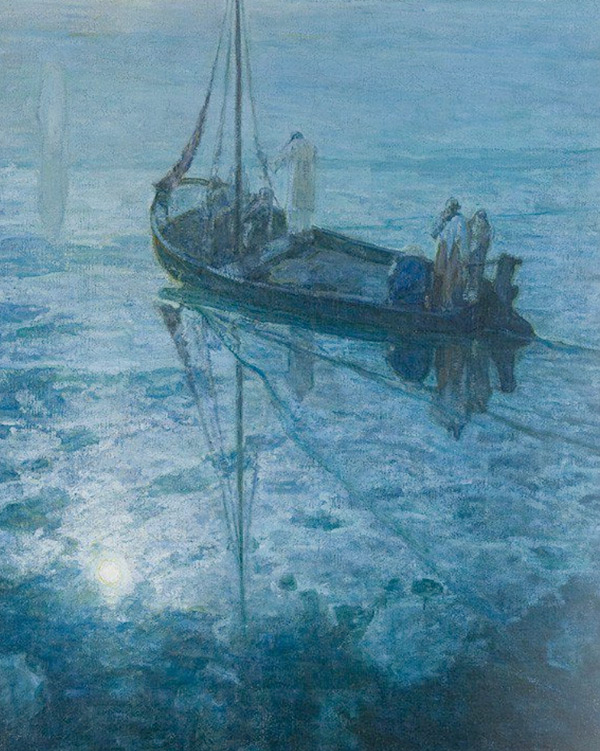

In chapter 2, James Romaine demonstrates the shift in Henry Ossawa Tanner’s paintings from the visual clarity favored by nineteenth-century academic art to a mood of personalized spiritual mystery favored by the twentieth-century symbolists. He examines four paintings as representative of this move—The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896), Nicodemus (1899), The Two Disciples at the Tomb (ca. 1906), and The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water (ca. 1907)—revealing how each explores the complex exchange between vision and belief.

Henry Ossawa Tanner: The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water

In chapter 3, Caroline Goeser examines the seven gouaches Aaron Douglas made in response to James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. These images align biblical narrative with modern black experience to tell socially resonant stories. In its attention to the African Simon of Cyrene, for example, The Crucifixion (1927) promotes an “Ethiopianist” narrative, influenced by the late nineteenth-century biblical scholar Edward W. Blyden. Simon looms large as the most prominent figure, heaving Christ’s heavy cross over his shoulders, heroized by his vigorous stride and his active gaze toward God’s light above. Bearing similarities to that of the trudging African American migrant in Douglas’s On de No’thern Road (1926), this pose subtly associates the Great Migration north with the burdensome road to Calvary.

Aaron Douglas: The Crucifixion

In chapter 4, Jacqueline Francis examines the dozen or so paintings Malvin Gray Johnson created between 1927 and 1934, the final years of his life, as visual interpretations of Negro spirituals. Modernist in style, these paintings, she says, united old and new and high and popular expressions, helping to revive and elevate this genre of black folk music that saw diminishing audiences during the Great Depression. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot (1928), a night scene painted in thick, dark hues and mounted in a gold lunette frame reminiscent of medieval icons, received the most critical attention in Johnson’s time, eliciting comparisons to Albert Pinkham Ryder. The artist said,

I have tried to show the escape of emotion which the plantation slaves felt after being held down all day by the grind of labor and the consciousness of being bound out. Set free from their tasks by the end of the day and the darkness, they have gone from their cabin to the river’s edge and are calling upon their God for the freedom for which they long. (qtd. 56)

In chapter 5, Phoebe Wolfskill demonstrates how Archibald J. Motley Jr.’s paintings represent a middle-class bias and a subtle derision of the behaviors of the “emotional” black masses, from whom he, a Catholic, sought to separate himself. When he was young Motley moved with his family into a white Chicago neighborhood decades before the Great Migration brought working-class African Americans up north, and he studied at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago. His membership in the Catholic Church, a large, established institution, further signaled his social standing. Wolfskill contrasts Motley’s less than empathetic treatment of demonstrative religiosity in the genre paintings Tongues (Holy Rollers) (1929), Gettin’ Religion (1936), and Getting Religion (1948) with the respectable, constrained practices of Catholic devotion suggested in his portraits Mending Socks (1924) and Self Portrait (Myself at Work) (1933).

In chapter 6, Amy K. Hamlin analyzes the formal qualities of William H. Johnson’s Jesus and the Three Marys (ca. 1939–40) and discusses the artistic and historical-cultural influences behind it. Influenced by the German expressionism Johnson encountered during his time in Europe and through his artist brother-in-law Christoph Voll, this painting holds naturalism in tension with abstraction—flattened space, an inscrutable middle form, among other elements. Hamlin suggests that Johnson chose the subject of the dead Christ in response to the increase of lynchings in the United States during the interwar period, pointing out its visual correlations to Johnson’s Lynch Mob Victim (not reproduced), which also features three female mourners.

In chapter 7, James Smalls considers the black male nude sculptures that constituted a primary focus of Richmond Barthé’s oeuvre. Such figures are rare in African American art, considered forbidden territory because of “what the exposed black body has come to signify for many African Americans—that is, a vulnerable body often exploited as a site of pain, trauma, and sexual violation—and never a body of ‘true’ agency and/or liberation” (88).

Richmond Barthé: The Mother

Smalls’s central assertion is that Catholic Barthé’s love of classical sculpture was just a pretext for indulging his homosexual desires, and that he tried to deflect his sculptures’ erotic impact by presenting their subjects in religious terms (91). This claim is, I feel, an overreach. None of the four illustrations in the chapter—Tortured Negro (1928), The Mother (1935), Birth of the Spirituals (Singing Slave) (ca. 1941), Come unto Me (1944–47)—strike me as erotic, and Smalls offers little to no support for his reading of them as such. The second, for example, shows, in Barthé’s words, a Negro mother receiving into her arms at the foot of a tree the body of her lynched son (you can see visible rope marks around his neck), in a pose that recalls the Pietà of church tradition, and yet Smalls insists it “promote[s] erotic desire” (91). He says the haggardness, the earthboundedness, of the Christ figure in this and other similar sculptures by Barthé distances it from its prototype, whereas I would counter that these very qualities mark Christ not just in scripture and creed but in centuries worth of passion imagery that reminds us of Christ’s suffering in the flesh (visible indicators of divinity or transcendence were not always present). And as for the exposed genitalia, Renaissance artists often used this device in paintings of the infant Christ as a way of asserting his full humanity. While I find Smalls’s thesis unconvincing, I nevertheless appreciate the attention he sheds on this artist who was new to me.

In chapter 8, Julie Levin Caro shows how Allan Rohan Crite’s serial drawings of Negro spirituals “refute the stereotypical tropes of the spirituals as the embodiment of a southern, black folk sensibility or the atavistic religious practices of slaves” (104), instead showing them enacted by contemporary, well-to-do, black Episcopalians in Boston, of which Crite was one. He wanted to reclaim the spirituals as religious “hymns,” part of the canons of Western liturgical music and concert music, and in his attempt to portray them as sophisticated, in his drawing captions (comprising lyric excerpts) he purged the vernacular English and wrote in a Gothic-inspired font. “Crite’s particular contribution to the history of American religious art challenges a bias within the discourse on racial identity in art that privileges an essentialized conception of black religious identity centered upon the ‘folk,’ or working- and lower-class African Americans, and a southern-based evangelical or fundamental style of worship” (111); here, instead, is the black middle class engaged in liturgical worship in the North.

In chapter 9, Elaine Y. Yau examines the visionary art of Sister Gertrude Morgan, who in 1957 was, by her own account, crowned the bride of Christ. At a time when interracial marriages were frowned upon, she represented herself, through numerous crayon drawings with scribbled text, standing in a white wedding dress alongside a white Jesus.

In chapter 10, Edward M. Puchner sheds light on the salvaged limestone sculptures of Nashville stone carver William Edmondson, who started sculpting in response to a command he received from God in a vision, filling his backyard with Crucifixions, angels, animals, preachers, and public figures. Museum of Modern Art director Alfred Barr’s interest in Edmondson’s work, which he classified as “modern primitive,” led to a solo exhibition at the MoMA in 1937 (he was the first African American to receive that honor). Until his death, Edmondson maintained a tombstone carving business and a modernist sculpture studio, fulfilling the needs of two separate audiences. Puchner focuses on the artist’s personal religious convictions, often overlooked in scholarship, as a key to understanding his art, and spends the most time on his Crucifixion.

In chapter 11, Richard J. Powell discusses Horace Pippin’s ten biblical paintings, most notably his Holy Mountain series inspired by Edward Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom paintings.

In chapter 12, Carla Williams discusses James VanDerZee’s photographs of churches as service and social organizations within the Harlem community, and of black religious leaders. She contrasts his double-exposed Daddy Grace (1938), a flamboyant celebrity preacher of the prosperity gospel depicted on a stage before throngs of worshippers, with Barefoot Prophet (Elder Clayhorn Martin) (1929), a modest and unassuming follower of God who is depicted alone, deep in prayer before an open Bible and a crucifix.

In chapter 13, Kymberly N. Pinder examines key works from Romare Bearden’s 1945 Passion of Christ series, questioning whether abstraction is a fitting vehicle for religious themes. The essay contains several quotes from the artist and places him in a larger context of twentieth-century religious painting. It’s frustrating that of the three Bearden paintings reproduced in the chapter—Madonna and Child (1945), The Visitation (1941) and He Is Arisen (1945), though all compelling in their own right—none are from his Passion series, the essay’s main subject.

In chapter 14, Kristin Schwain looks at how Jacob Lawrence, when commissioned to illustrate the first chapters of Genesis, chose to visualize a black preacher’s evocation of the narrative for his parishioners (that is, its oral performance) rather than the written text itself. The sermonic invocation conjures biblical imagery of the different stages of creation in the four arcade windows in the background. These eight gouaches were inspired by Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the senior pastor of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, where Lawrence attended. Each contains the same five elements—a preacher at the pulpit, a congregation in the pews, a set of windows, a box of carpentry tools, and a flower vase—but through creative variation, the composition avoids repetitiveness. (see the first one, In the beginning, all was void, on the book cover above)