.jpeg)

Out of the Ashes

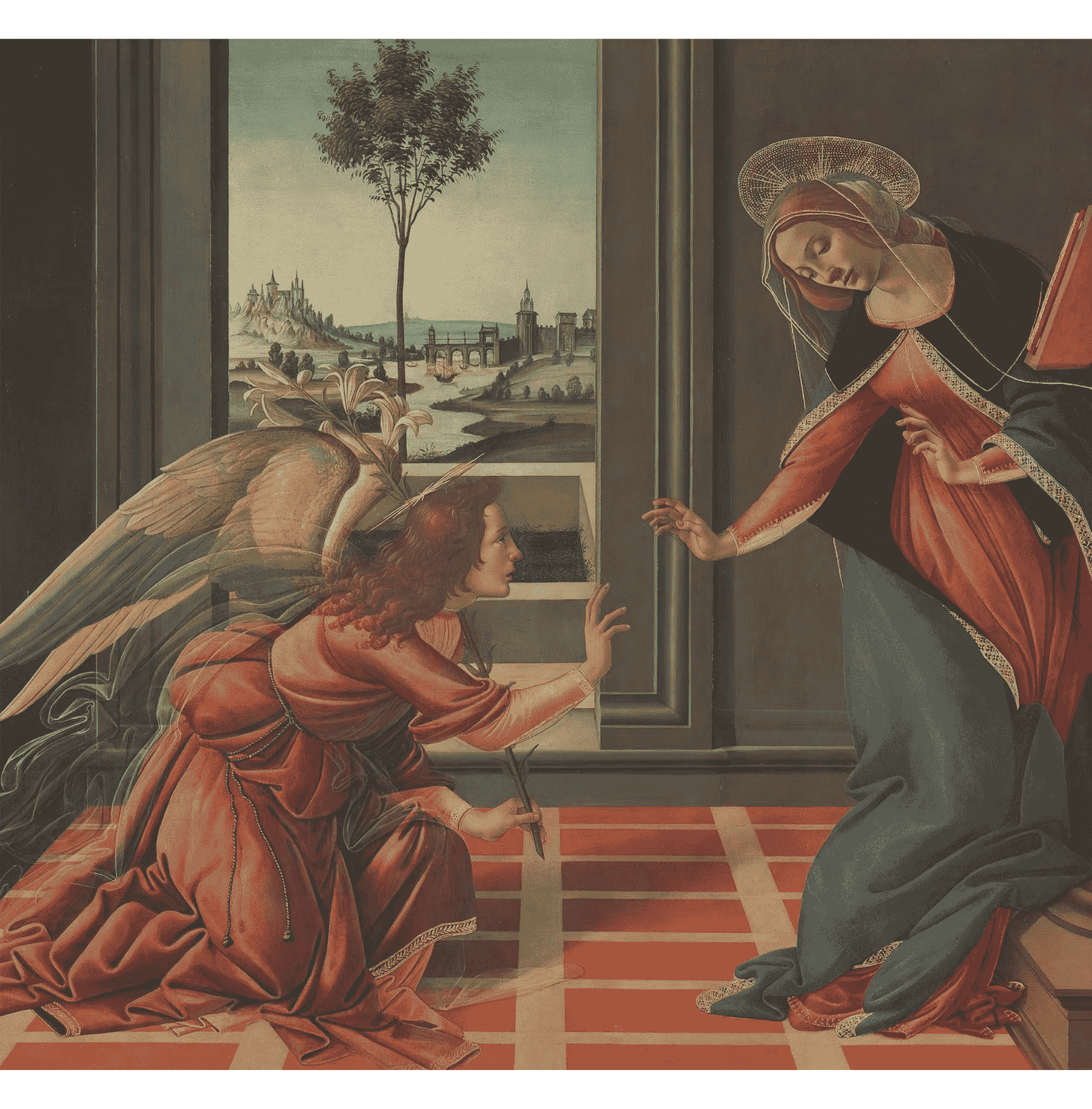

The 1940 bombing of the Anglican Coventry Cathedral provided the first major opportunity in England to combine modern religious art and architecture. Architect Basil Spence, whose designs were chosen from among the 219 submitted, called for the new structure to be built beside (not over) the ruins of the old one. “I saw the old Cathedral as standing clearly for the Sacrifice, one side of the Christian faith,” he wrote, “and I knew my task was to design a new one which should stand for the Triumph of the Resurrection.”

As part of this task, Spence invited Graham Sutherland to design an enormous tapestry (larger than a tennis court) on the subject of Christ in Glory to serve as the dominant feature of the interior.

Over the several years he spent working out a design, Sutherland made hundreds of sketches. An undated letter he wrote gives us a glimpse of his approach:

I am making experiments in the most difficult of all the questions—the Christ. The figure must look real—in the sense that it is not a rehash of the past. It must look vital; non sentimental, non-ecclesiastical; of the moment: yet for all time.

After seeing Sutherland’s first cartoon, Provost Richard Howard wrote to him saying,

The face of Christ is going to be your greatest work and I am sure you will succeed. Victory, serenity, and compassion will be a great challenge to combine. Just as the Italians boldly conceived an Italian face for Christ and the Spanish a Spanish face, it may come to you to conceive of an English face, universal at the same time.

.jpeg)

In a conversation with Andrew Révai shortly after the tapestry’s completion, Sutherland further described his intentions:

I felt that it must contain, together with the humanity of Christ, a sense of the power of Christ, in so far as Christ is also God. I did not want a Jehovah by any means, but on the other hand I wanted the look of the figure at least to have in its lineaments something of the power of lightning and thunder, of rocks, of the mystery of creation generally—a being who could have caused these things, not only just a specially wise human figure. My idea, then, was to make a figure which was a presence.

The end result is a frontal, short-bearded Christ with arms bent up at the elbows, wearing a priest-like robe and encircled by a mandorla. The Holy Spirit hovers over him, and the glory of the Father shines down and about. Between his feet is a life-size human figure, giving a sense of scale. Below that is a dragon in a chalice—a reference to Satan being “conquered . . . by the blood of the lamb” (Revelation 12:11).

.jpeg)

Sutherland’s Christ is surrounded by four winged creatures—symbols of the four evangelists—connected to one another by golden bands. Creating asymmetry on the right side is the cathedral’s namesake, St. Michael, defeating the dragon of Revelation (12:7–8).

While the Christ in Glory portion of the tapestry forms a reredos to the cathedral’s high altar, the Crucifixion scene at the bottom forms a reredos to the Lady Chapel. To the right and left of the crucified Christ the sun and moon cover their faces and weep. A purple veil behind his body—probably an allusion to the temple veil—emphasizes his paleness, and behind him a bier with a cloth draped over it lies ready to receive him.

.jpeg)

The weaving of the tapestry was carried out by the firm of Pinton Frères in Felletin, France—near Aubusson—under the artistic direction of Madame Marie Cuttoli. (As it was decided that the tapestry would be woven in one piece, Pinton Frères was one of the few workshops worldwide to possess a loom large enough.) It was a feat indeed, one that took four years and twelve weavers to complete.

Sutherland’s Coventry Tapestry pulsates with energy, from the flapping of wings to the tumbling of bodies to the Trinitarian rings of light, yet centers on the still, steady, loving presence of Christ Almighty. In the shadow of his cross and the glory of his resurrection, we have life; we, like Coventry itself, rise victorious from the ash.

**********

SOURCES:

Basil Spence, Phoenix at Coventry: The Building of a Cathedral (New York: Harper & Row, 1962).

Louise Campbell, Coventry Cathedral: Art and Architecture in Post-War Britain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996).

Andrew Révai, ed., Christ in Glory in the Tetramorph: The Genesis of the Great Tapestry in Coventry Cathedral (London: The Pallas Gallery Ltd., 1964).

*******

Graham Sutherland: Christ in Glory in the Tetramorph, 1962. Tapestry, 75 × 38 ft. Coventry Cathedral, Coventry, UK.

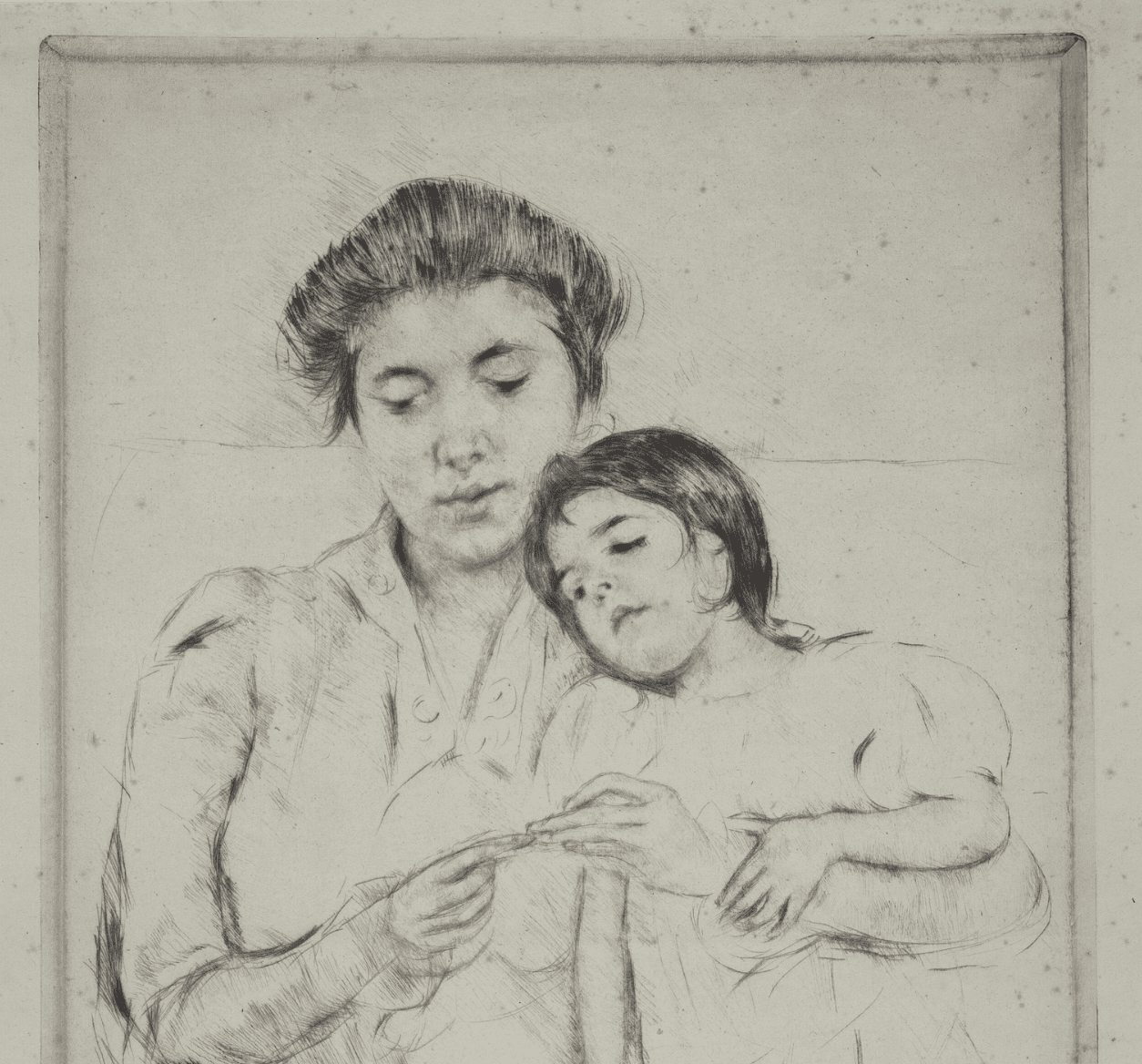

Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) studied engraving at Goldsmiths College in London from 1920 to 1925. He turned to painting in the 1930s and quickly gained an international reputation. During World War II he was named an official war artist for Britain, an experience that shaped the remainder of his career. A convert to Roman Catholicism, he painted his first religious scenes in the late 1940s—images of Christ’s passion informed by and commenting on the horrors of the Holocaust. In the 1950s he found his strength in portrait painting. Labeled a Neo-Romantic, Sutherland belonged to no school but was regarded as a master in his own right. He participated in many exhibitions that confirm his international reputation, including the Documenta in Kassel in 1955, 1959, and 1964. He had an enormous impact on the next generation of artists in England.

Victoria Emily Jones lives in the Baltimore area of the United States, where she works as an editorial freelancer and blogs at ArtandTheology.org. Her educational background is in journalism, English literature, and music, but her current research focuses on ways in which the visual arts can stimulate renewed theological engagement with the Bible. She is in the process of developing an online biblical art gallery, a selective collection of artworks from all eras that engage with specific texts of scripture. Follow her on Twitter @artandtheology.

ArtWay Visual Meditation October 2, 2016

%20(1).png)