Liberation in Luke’s Gospel: An Artistic Appreciation and a Theological Analysis

Introduction

Liberation in Luke’s Gospel is one of the books of Pulidindi Solomon Raj with his art and poetry. It may be considered the magnum opus of Solomon Raj, on par with his seminal work, ‘A Christian Folk Religion in India: A Study of the Small Church Movement in Andhra Pradesh’. Though it is not voluminous (actually it contains 40 pages), it has been widely known globally, being published in German (1991), Dutch, English (1996), and Telugu (2010) languages. As the subtitle in the English edition shows, this book is a conspicuous combination of ‘Image and Word’ emerging from the paintbrush and the pen of Solomon Raj. The artist has done these color woodblock prints during 1987-88, as part of his research study at Selly Oak Colleges, England, where he was a professor of cross-cultural communications.[#1][1][#1] The purpose for which this publication was made, in author’s words, was “for meditation, Bible study and prayer in groups”.

The present paper has a three-fold purpose: It traces a brief historical development of these works, presents an artistic appreciation, and brings out a theological analysis of the themes embedded in these works. For the sake of readers who are new to the art of Solomon Raj, and to refresh the memory of those who knew this series, reproductions of the twelve wood block prints, dealing with the theme of this essay, are given in the body of the text.

Historical Development

In the author’s Introduction to the book in English, we find how Solomon Raj was impressed by the ‘liberation motif’ found in the most familiar texts of Luke’s narrative, and how he was inspired to produce all these 12 wood block pictures on a single theme, namely, the hand of God at liberation. He chronicles the origins of this work in a simple, yet significant manner:

I was reading the gospel according to St. Luke in the Bible searching for passages related to freedom, liberation or what may be called redemption. Humanity, nay the whole creation needs liberation, a liberation from many kinds of bondage. So I made these pictures to bring out the idea of liberation or freedom. With each picture I have written short meditations … the outcome of my quick reflection on each text.[#2][2][#2]

According to Fr. Ubelmesser S.J., the Mission Office in Nuremberg dedicated Christmas issues of their magazine each year to a special subject on inculturation, presenting the work of a particular artist each time. Their magazine for Christmas 1984 contained eight works of Solomon Raj. “They are embedded in photos of dalits and tribals, as well as in texts of dalit literature; and this at a time, when the struggle for dalit liberation was still fresh and new, even in India.”[#3][3][#3] When Dalit Liberation Theology was taking shape in Bangalore, South India with the reflective views of A. P. Nirmal, and was emerging as a movement to reckon with in early 1980’s, Solomon has taken this message, almost simultaneously, beyond the borders of India through his art and reflective verse. In 1988, the Nuremberg Mission Office published The Living Flame and the Springing Fountain by Solomon Raj with 30 pictures of his batiks, which is out of sale (just a few copies left in the archives). The Indian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (ISPCK), Delhi published the English text edition of this book in India. The Christmas issue of Nuremberg Mission’s magazine in 1991 was again entirely dedicated to the works of Solomon Raj, this time on Liberation in Luke’s Gospel.

The art in this book has been used in Chicago in recent years and this accounts for its continued impact on the successive generations. The Lutheran Church of St. Luke of Itasca, Illinois has thoughtfully used these twelve woodcuts as basis for their ‘Meditations for the12 Days of Christmas’, commemorating their centennial. Solomon was very appreciative of this work and the commentary involved in the project: This is the kind of response I always welcome. My artwork is not prescriptive or restrictive in any sense, but it aims at being evocative. That means that the viewers are welcome to bring their own experience and perception into play when they see the works and express their own ideas.[#4][4][#4]

Artistic Appreciation

In his Foreword to this book, Bishop Sam Amirtham extols the liberation motif in the Bible, which was artistically portrayed by Solomon Raj as follows:

Our God is a God of liberation. We know this from the history of the Hebrew tribes who, by God’s hand of deliverance, successfully escaped from the bondage in Egypt. This Exodus paradigm is repeated over and over again throughout the books of the Bible, even unto our present times. God’s liberation has been experienced again and again by different peoples throughout history. It is a historic reality … The birth, the life and the ministry of Jesus Christ constitute the supreme act of God’s liberation for the whole world. St. Luke, the physician, researcher and evangelist, put in a lot of historical research in painting his Gospel narrative of the liberation stories of our Lord. The physician chose a particular and unique perspective to present the Gospel as he saw it: the liberation in Christ Jesus.[#5][5][#5]

Amirtham further appreciates Solomon Raj and his contribution in this significant book:

Dr. Solomon Raj, resting in St. Luke’s tradition, uses pictures, poetry and prose to articulate this liberating messages [sic] of Jesus Christ in this gospel according to Solomon Raj. It is an original contribution of the Indian church to the whole Oikumene.[#6][6][#6]

Having a close association with the artist, Fr. Ubelmesser extols the work of Solomon Raj and the ethos of such religious art, from a first- hand experience:

His paintings, batiks, woodcuts and his verses are in all their Indian garb a beautiful expression of our common faith in Jesus Christ and his gospel. After all he has spent most of his life just doing this: integrating our faith with brush and word.[#7][7][#7]

The wood block printing technique had its superb expression in the hands of Solomon Raj in the cut and the colour of each work. In fact, each work is a masterpiece by itself with beautiful imagery and rich indigenous symbolism. In the Telugu text edition of this work, Solomon presents a brief description of the Signs and Symbols used in these works. They are familiar to the Church across the past 2000 years as they emerged from the imagination and portrayal by artists. K. Sam Mathew made an interesting study of Solomon’s symbolism when he submitted his dissertation for Master of Theology to the Senate of Serampore College,[#8][8][#8] though this study was limited to indigenous symbols in selected Batiks of Solomon. The signs and symbols are like ‘mini parables’ with a voice of their own and a meaning.[#9][9][#9] A mention is made of the symbolism in each of these works with their particular meaning and message as we move through the following analyses.

A Theological Analysis

The titles of the works in the book, and the distinct types of liberation they envisage may be listed as follows:

1. The Handmaid of God - Liberation from Social Prejudices

2. Darkness and Sin - Liberation from Darkness

3. Oppressors and the Oppressed - Liberation from Oppression

4. The Lord Remembers the Hunger - Liberation from Hunger

5. We and They - Liberation from Barriers

6. More Love and More Forgiveness - Liberation from Guilt

7. The Fourfold Bondage - Liberation from Bondages

8. Demons and Devils - Liberation from Demonic Powers

9. Needle in the Haystack - Liberation from Too Many Cares

10. Body and Soul - Liberation from Bodily Concerns

11. Burdens of this World - Liberation from Burdens

12. Gentle Brother Death - Liberation from Fear of Death

An analysis of these12 works is in order at this juncture. This analysis will be two-fold: a general treatment with artistic significance and a theological analysis with their specific message. Since the primary focus of all these works is liberation, the order of the sub-titles is used in the following analysis, instead of the ‘imaginative titles’ given by the artist to each of these works.

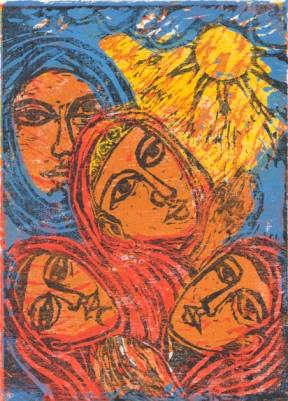

1) Liberation from Social Prejudices

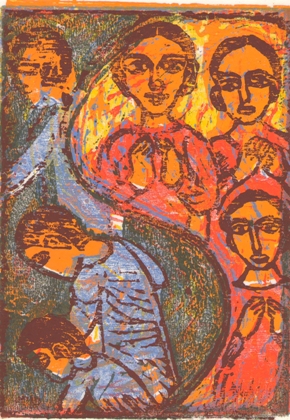

The first work, entitled ‘The Handmaid of God’ is based on Luke 1:48, which reads, “For he has looked on the humble estate of his servant. For behold, from now on all generations will call me blessed”. This is from the Magnificat, ‘blessed’ Mary’s Song of Praise, which extols the theme of the bonded becoming the blessed, and this reminds us of ‘gender liberation’.

The prejudice for women in the Jewish society needs no mention for anyone who knows the Jewish Prayer: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our G_D, King of the universe, Who hast not made me a woman”. And also the prayer to be said by a Jewish man everyday: “Thank God for not making me a Gentile, a woman or a slave” (from Jewish Talmud). And the prejudice for a place is also obvious in the way the town of Nazareth, from where Mary hailed, was belittled: “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” (John1:46). Whether women are spoken high, or treated low, the artist could see the divine perspective that leaves no room for ‘social prejudice’ in the last stanza of his meditative reflection:

For all that we know

when God decided to become incarnate

He chose to enter

the womb of a woman.

Solomon Raj emerges as a Champion of Women Liberation, deliberately or otherwise. In the Telugu edition of this work, the author concluded each reflection with some profound sayings – expressed in couplets and stanzas. The saying at the end of this first work reads like this:

He has gone and seen the depths of divine will Who desires the progress of womankind. (stree jaati pragatini aasinchuvaadu daiva sankalpaambudhini digi choochinaadu).[#10][10][#10]

The symbol of star in gold color at the right upper corner, which the author mentions, is a sign for heaven and for divine revelation. Viewing it as sun, it is commented that as the sun “brings the light that frees all humanity from darkness”, “Humankind, represented hereby the four women, waits for the coming of the Light of the World in a spiritual sense”.[#11][11][#11] It is interesting to know that Solomon has produced a similar series of 12 wood cuts, on ‘Jesus with the Women’.[#12][12][#12]The artist upholds the place of women through these twelve portraits of women. The book with these woodcut prints by Solomon, with matching devotions by Jorg Dantscher, S.J. was published in German a decade ago.

2) Liberation from Darkness

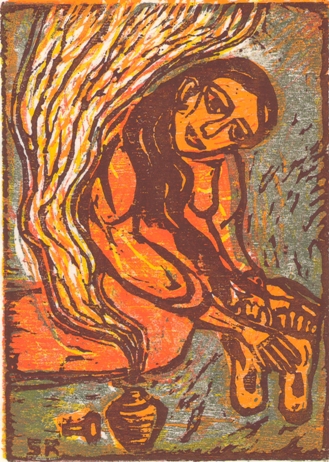

The second work entitled ‘Darkness and Sin’ is based on Luke 2:30-32 containing Simeon’s song: “For my eyes have seen your salvation that you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to your people Israel.”

Jesus is portrayed here as ‘a light for revelation’ granting ‘liberation from darkness’. The author reminds us of how the Indian sages had prayed from times immemorial: ‘Tamas’oma Jyothirgamaya’ (the meaning of this Sanskrit sloka being –‘Lead me from Darkness into Light’), and he hastens to declare:

Light is knowledge

Light is wisdom

Light is a sign of immeasurable holiness.

When God made the dance of creation

Light was born first.

The adjective that qualifies ‘holiness’ is very profound: ‘immeasurable’ since it is infinite; ‘holiness’ is not something relative but is an absolute, as it is one of the essential and eternal characteristics of God; the holiness of God, which is infinite and immutable!

The author was aware of the beliefs of other faiths and makes an allusion to the image of ‘dance of creation’ as he talks about creation by God. According to Hindu mythology, Shiva ‘tandava’ is “a vigorous dance that is the source of the cycle of creation, preservation and dissolution”.[#13][13][#13] Though the author may not adhere to this belief, he adapts this imagery when he talks about the creation of light by God at the very outset, as in the Biblical narrative. And a genuine prayer is penned in the closing stanza for personal enlightenment as well as for universal awakening:

So give me the gift of Light

let darkness be cast behind

and let the universe be awakened

into that glorious morning

which shall not be darkened

by another night.

Light is acknowledged as a ‘gift’ from God, and as such it cannot be attained but only be received. And the recipient of this ‘gift of Light’ experiences liberation from darkness, as darkness is ‘cast behind’ by a power higher than one self, even God Himself coming to the rescue of helpless mankind. Peoples are shown in the picture to be drawn from all over to the light for revelation. Gerald A. Danzer reflects and comments about the figures in the picture as follows:

The golden light emanating from the four figures in the background, angels or perhaps the four gospel writers, shatters the darkness. Four corresponding figures at the base, perhaps representing the church today, seem to join Simeon in singing the Nunc Dimittis. As Martin Luther paraphrased Simeon’s message: ‘Christ is the hope and saving light of those in blindness. He guides and comforts those in night by his kindness’.[#14][14][#14]

A slight reference may be seen here to the fatal fall of man when Satan tempted, and consequently the universe, as well as the heart of man, was darkened. The concluding reflection in the Telugu edition conveys the following meaning:

The mind of the wicked that loves darkness cannot see there is such thing as Light; Those who desire the state of darkness cannot smell the Heavenly Light.[#15][15][#15]

The author anticipates with prophetic hope, ‘that glorious morning which shall not be darkened by another night.’

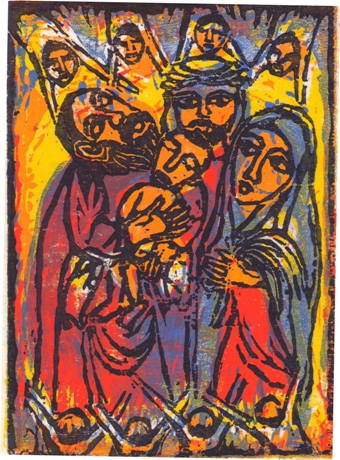

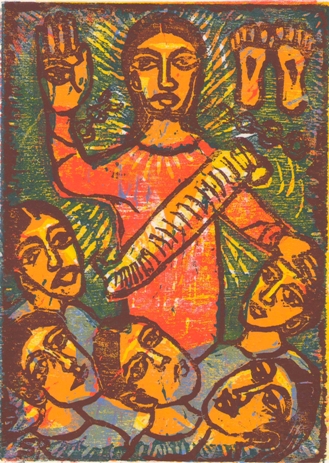

3) Liberation from Oppression

The third work, ‘Oppressors and the Oppressed’ is based on Luke 1:52-53, which reads: “He has brought down the mighty from their thrones and exalted those of humble estate; he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty.” This again is taken from the Magnificat. The curse of sin upon mankind necessitated the Incarnation! Here is a beautiful imagery of a tree –‘the tree of sin’ bearing the fruits of ‘classes and castes’, and ‘unjust structures’ heaping oppression and injustice upon mankind.

The outcome of the ‘unjust structures made by man’ is graphically described:

Some get rich at the cost of the poor

some get fat

from the perspiration of the week.

Classes and castes not only perpetuate the existence of the oppressed and the oppressors, but they serve their contradicting destinies as ‘rungs for the high’ and ‘crushing berths for the poor’. There is rich symbolism in this work. The wheel in the center is a sign of divine fullness and perfection. The Lord’s wounded hand is within the circle. Here we see the thumb and the pointing finger joined, which symbolize the unity of Christ’s divine and human natures. Danzer with intent reflection makes a lucid comment:

The hand of Jesus, bearing the scar of the crucifixion, is raised in blessing. The artist explains: ‘The thumb and the first finger is the Byzantine symbol of Christ blessing and teaching. This is a well-known symbol from Eastern Orthodox iconography connecting the two natures of Christ, the human and the divine … I have used this symbol many times to indicate the two natures of Christ.’ The six followers that Solomon Raj places around the circle of blessing have looked and have seen. They seem to come away from the blessing in a variety of moods. One lifts up his arms in a sign of victory; others look like they have resolved to follow a certain course of action. And still others are singing hymns or reciting psalms. All show individual expressions on their faces, but their arms and hands seem to converge in fellowship. The circle of the believers is where the hungry are filled with good things, where the celebration is held.[#16][16][#16]

As the scriptural foundation spells above, God the Equalizer ensures ‘Justice for All’ by His two-fold intervention: bringing down the mighty from their thrones and exalting the humble; and filling the hungry with good things and sending away the rich empty. The author longs for the advent such a redeemer and the redemption He grants:

The redeemer will bring justice to the poor one day

taking his place

with those who are oppressed.

The Redeemer identifies with the oppressed, as “He was oppressed and afflicted” (Isaiah 53:7) and ultimately takes his place with them when he took their sorrow and suffering, and died on the cross.

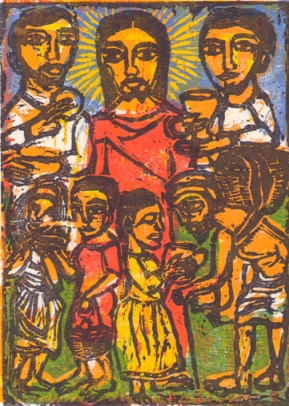

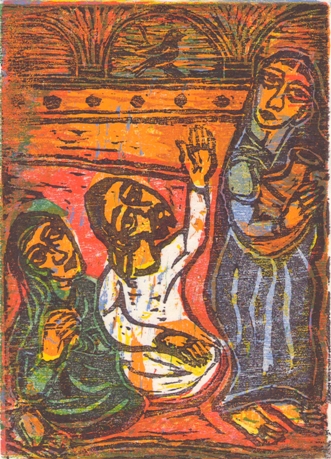

4) Liberation from Hunger

The fourth work entitled ‘The Lord Remembers the Hungry’ is based on Luke 22:19 which reads: “And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’”

Using this passage related to the ‘Last Supper’ Solomon Raj communicates the truth that the Lord remembers the hungry and ensures liberation from hunger for all such people. The Lord’s body given for others not only satisfies the spiritual hunger of people, but also challenges and enables them to feed the hungry. Thus the author encourages the reader to participate in this ministry of sharing, which ensures the prospect of a great reward:

Break the bread, break the bread

share your bowl of rice

there are many hungry souls around.

Give your cup of water

to a thirsty child

and your reward will be great.

Break your bread, break your bread.

Whenever you share your bread

and part with your cup

there is always communion.

God is surely present in

that bread and the cup.

As Danzer remarks, Solomon combines two familiar incidents in the life of Jesus in this work:

The feeding of the five thousand near the start of his ministry and the institution of the Lord’s Supper towards its end. In between these two events Jesus directs every disciple to work for freedom from hunger in every sense of the word – physical, mental, and spiritual. The lateral movement in the image suggests that working for freedom from hunger, a mandate given to each individual disciple also has a group dimension. Note that one follower shoulders a large basket at the end, one of the twelve containers in Luke’s story … These symbols of God’s superabundant grace announce a time for thanksgiving.[#17][17][#17]

5) Liberation from Barriers

The fifth work, ‘We and They’ is based on Luke 13:29 which reads: “And people will come from east and west, and from north and south, and recline at table in the kingdom of God”. The Divide between the human community resulting from man-made barriers and the predicament of such discrimination is well brought out in the following lines:

Who is in, who is out

in these man-made boundaries?

Trenches that people cannot cross

Walls that nations cannot scale.

The scribe would not eat with

the so-called sinner

the Pharisee not with the publican.

Castes do not mix

colours do not blend.

Yin will keep off from the Yong.

Danzer comments that the barrier is a dynamic line that separates the ‘red-robed saints on one side and the blue individuals on the other. He further describes:

The reds, with hands folded, seem to be leading the procession to the banquet hall. The blues, on the other hand, are in sad disarray. Their eyes seem to be cast down; maybe they have been cut off from the march by a human barricade. They need to scramble to find a place at the end of the line. Jesus realizes their plight; he knows the discrimination they face. His next words comfort them, ripping out obstacles to faith and obstructions to fellowship: ‘There are those who are last who will be first’. And then, when all have their places, a mighty chorus erupts in praise and thanksgiving.[#18][18][#18]

The author laments about these manmade barriers, which keep humankind apart, and he graphically portrays this Divide through the symbol of Yin Yong. On one side are the depressed and the downhearted while on the other side we see those who rejoice. The line that divides these two must go away and all must share the joy of the Lord. And the artist anticipates that day when east shall meet with the west (across the continents) and north with the south (within the nations), and ultimately ‘saints and sinners shall share the kingdom of God’.

6) Liberation from Guilt

The sixth work, ‘More Love and More Forgiveness’ is based on Luke 7:47 which reads: “Therefore I tell you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven – for she loved much”. In a dramatic incident at a prominent Pharisee’s house, a sinful woman had done something that is forever memorable. The artist reflects on the ensuing theme of forgiveness in simple but beautiful verse by means of an immutable equation:

The more my sins

The more is my love.

The more my love

The more is the forgiveness

I receive.

The title in Telugu is loaded with strong adjectives meaning ‘Infinite Love –Incomparable Forgiveness’ (Amitamagu Prema – Atulitamagu Mannimpu). Mary here adores the feet of Jesus, which are portrayed through just the sign of His wounded foot. The perfume that ascends is a symbol of prayer that rose up from her heart. This woman of ‘ill repute’ entered the room ‘uninvited’, and her tears of remorse and repentance knew no bounds as they wet Jesus’ feet. She endeavours to dry them with her hair and in the process kissed them and anointed them with a precious perfume. Danzer aptly comments:

It was quite a scene and the artist has dramatically portrayed the fragrance of the ointment rising like incense, carrying the woman’s prayer to the heavenly throne. Simon pointed to the women’s sins, heaping on her guilt. Jesus, however, struck by her love, forgave her the many sins she had accumulated.[#19][19][#19]

The artist uses rich imagery as he explains the grand outcome of the event. Just as the snowmelts when the sun shines on the icy peaks, ‘the dirt and the dust get washed away down the hill’ when the tears of repentance flow from one’s heart. And the sinful woman became a sanctified woman, when God’s gracious forgiveness was granted in response to her genuine act of penitence. His joy and His peace filled her heart as the ‘perfume’s captivating aroma’ filled the room. Gone was the guilt, which had a heavy toll on her for long until she came to the Lord. Though she approached Jesus and entered the room ‘uninvited’ the compassionate Lord proved that no sinner who comes to Him will ever be cast away.

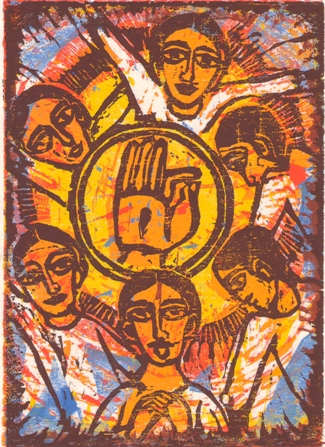

7) Liberation from Bondages

The seventh work entitled ‘The Fourfold Bondage’ is based on Luke 4:18 which reads:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.”

This picture shows Jesus reading the scroll from prophet Isaiah when he first visited the synagogue at Nazareth. This so-called Nazareth Manifesto of Jesus envisages the four-fold liberation, which symbolizes ‘the coming of the kingdom of God’. The artist reflects on this as he heralds the Good News of hope:

The poor and the hungry

the oppressed

and the downtrodden;

the casteless and the cast out

shall hear the good news

of hope.

This shall be the coming

Of the kingdom of God.

The Kingdom of God is the embodiment of the ‘goodness of hope’ - nothing less and nothing else! The four-fold liberation here is portrayed through rich symbolism. We see an eye on the right hand of the Lord, and this is a sign that the blind will see! In the upper right hand corner we see the wounded feet of Jesus, and this is a sign that the lame will walk! There is a broken chain around the head of the Lord, and it is a sign of ‘liberty to the captives’ and the oppressed! And finally we see a scroll around the shoulder of the Lord, and this is a sign of the ‘good news to the poor’! Danzer points out another significant symbolism when he says, “Our Lord has one hand raised in proclamation, the other set in blessing”. Danzer further makes a shrewd remark about the response to Jesus’ sermon:

At first the homily was well received; soon afterwards the congregation rose up in rebellion. But the old message of freedom, recovery, sight, emancipation, and grace remained timely. The shawl reminds us of the scroll from which Jesus read. His feet, nail scars and all, suggest the way of the cross.[#20][20][#20]

8) Liberation from Demonic Powers

The eighth work ‘Demons and Devils’ is based on Luke 8:33 which reads as follows: “Then the demons came out of the man and entered the pigs, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and were drowned”. In this dramatic scene, Jesus ordered a whole band of evil spirits to come out of an unfortunate man’ and delivered that demon-possessed man. Presenting the theme of ‘liberation from demonic powers from the story of the ‘Legion’, Solomon laments - ‘people in many lands still live in the fear of demons’ and therefore he longs for liberation for all:

We all need to be freed from demonic powers

from demons that bother us today –

demons, may be,

of a different kind.

In the Telugu version of this book, the different kinds of demons we find prevalent are hinted: the demon of drunkenness, the demon of discord and strife, the demon of lust for money, and the demon of corruption. We can still think about other demons such as racism, terrorism, gender discrimination, molest, domestic violence and so on, which plague our society today. Danzer points out how Solomon pictures the scene in three parts:

First there is the authoritative hand of the Christ at the upper left. The unfortunate man’s body, jolted by the exit of the demon host, dominates the picture, almost propelling the character off the page. Meanwhile the herd of pigs, ill-fated, plunges into the waters at the bottom of the panel. Our liberation from our own demons came at a great price, the suffering and death of our Lord. [#21][21][#21]

9) Liberation from Too Many Cares

The ninth work with the title ‘Needle in the Haystack’ is based on Luke 10:41-42, which reads as follows: “But the Lord answered her, ‘Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, but one thing is necessary. Mary has chosen the good portion, which will not be taken away from her.” Though the title is not a biblical phrase, it very well describes ‘the many cares that seem to pile up in our lives, reaching haystack proportions’. The search for the only one thing needed, as Jesus tells, suggests ‘looking for a needle in our haystack’. The artist remarks that in the good olden days, things like family, children and wealth to enjoy were considered ideals. But as things change, he points out, the world became more complex.

As a result,

Goals and values shift

desires and ambitions keep expanding

and in the haystack of too many cares

humanity lost the needle

of life’s compass.

Danzer comments as follows, extolling the blessed house, ‘where Jesus Christ is all in all’:

Look as hard as we might, neither the needle nor the haystack is evident in this print. Instead, with the hint of the text, we see the story of Mary and Martha. Luke tells us that Martha (on the right) invited Jesus into her home and was busy preparing the meal. Mary meanwhile was listening to the words of our Lord. In a fit, Martha demanded that Jesus send Mary to help her, but the Lord pointed to the one thing needful, the one that Martha had misplaced in her haystack of worries.[#22][22][#22]

Mary with folded hands is a sign of devotion and Martha tightly clutching her jar is a sign of anxiety and worry. The bird above on the branch is a reminder of God’s Word.

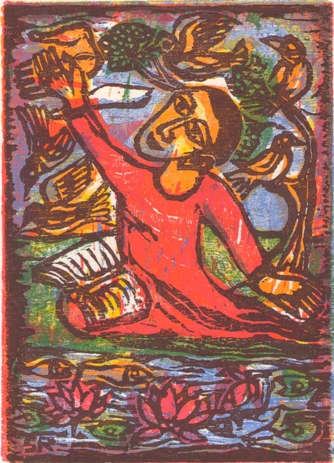

10) Liberation from Bodily Concerns

The tenth work entitled ‘Body and Soul’ is based on Luke 12:22-23 which reads as follows: “Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat, nor about your body, what you will put on. For life is more than food, and the body more than clothing.” The carefree ‘flowers of the field’ and the ‘birds of the air’ Jesus uses as a means of his didactic exercise, and through these He nails down the challenge of trusting God for all needs.

These three objects are beautifully pictured in this work – the birds above and the flowers below (which are Indianized and pictured as lotuses). The man who delights in the Law of the Lord is shown worry-free putting his hand in the hand of God. Danzer points out that this print, which focuses on bodily concerns, food and clothing, goes much further in making its point:

God cares for you, just as he attends to the

needs of birds and fish, flowers and trees.

The birds above and the fish below animate

this scene as everyman lifts up a hand

toward the heavens in praise to the

Almighty. An indistinct image (as in this

version of the prints) seems to uphold the

uplifted hand. It looks like a powerful hand

sustaining and blessing all of creation.[#23][23][#23]

Danzer further remarks that “The artist’s audience in India would immediately respond to the lotus blossoms, symbols of spiritual life and objects encouraging meditation. Freedom from worry about bodily cares emancipates the mind to tend to the soul.”[#24][24][#24]

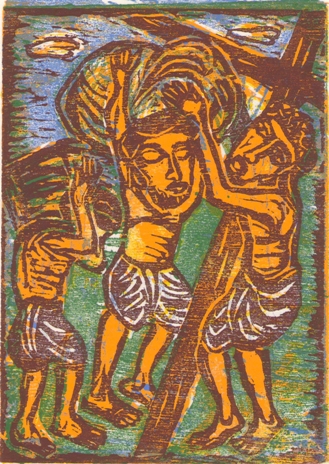

11) Liberation from Burdens

The eleventh work, ‘Burdens of this World’ is based on Luke 11:46 – “And he said, ‘Woe to you lawyers also! For you load people with burdens hard to bear, and you yourselves do not touch the burdens with one of your fingers’.” Solomon uses this text to depict the loads and burdens humans carry almost every day of their existence. He beautifully portrays the ‘Suffering Servant’ alongside humans, Who carried all the load of sin upon Himself on the cross. With much enlightenment on the philosophy of life, he conveys a fact in simple terms:

There are some things

which we know

and others

which we do not know.

We know there is suffering

in this world.

Many things, this side of heaven, we may not know; but we all invariably know ‘there is suffering in this world’. We often do not know the ‘why’ of it, in our own lives, and also in the lives of others. This ‘mysterious’ element of suffering is like a puzzle and every puzzle has its answer; it is only a matter of when we find it. With inner assurance the artist encourages: “We wait for God’s liberation from suffering, we wait for God’s answer”. The common tendency of the fallen human race is to shift loads instead of sharing burden. As a result some carry more of the burden and heavier loads than others. Danzer points this out as he comments:

The warning about not to load people with burdens they can hardly carry is one of six woes listed by Luke when summarizing one of our Lord’ stable talks. A positive command is implied in his follow-up observation about helping those who are struggling. The Apostle Paul later summarized Jesus’ message: ‘Carry one another’s burdens’.[#25][25][#25]

From his perception of the portrait, Danzer makes further enlightening comments:

The artist shows one person passing his load on to another, a person already burdened with his own baggage. And then there is a smaller fellow, maybe a youngster, crushed down by the weight of the freight he is carrying. But the compelling image in the picture is the cross, slashing across the scene, putting everything in perspective. Jesus carried our burdens, even to death on the cross. Our proper response to God’s mercy is to help free others from their burdens.[#26][26][#26]

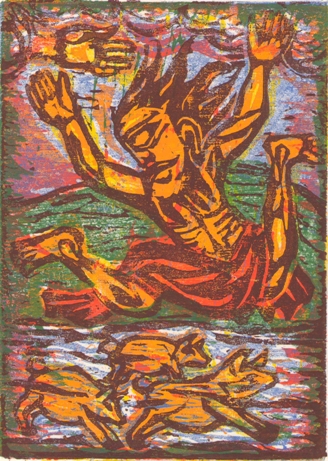

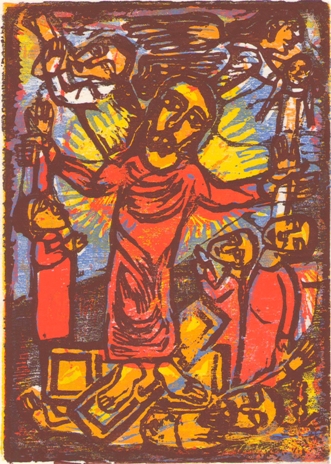

12) Liberation from Fear of Death

The last work, ‘Gentle Brother Death’ is based on Luke 24:1-2 which depicts the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The ‘imaginative title’ the Solomon gives to this portrait is ‘Gentle Brother Death’. This is obviously the description he borrowed from St. Francis of Assisi, who called Death as ‘Gentle Brother’. The artist in the accompanying verse addresses the many philosophical questions and perplexities about what happens after death:

At the time of death

where does the soul make its journey?

To the land of the fathers,

or the land of Gods?

Into the night or into the day?

Into the cloud or into the lightening?

Into the full moon or the new moon?

Into the dark fortnight

or the bright fortnight?

In the midst of these questions and perplexities, Solomon comes up with a certainty that has its scriptural foundations in abundance:

But we surely believe

that death is the doorway

to a new life

more glorious and more wonderful.

As Danzer comments, this last image in the series “pictures Christ the Liberator lifting people out of their coffins and giving them new life”. When Christ had conquered Death, the doors of death were broken, and Death was bound captive with chains at the feet of Christ. (The chains are clearly shown in the original version of the late 1980’s.) We see couple of angels above – one blowing a trumpet, which is a sign of resurrection; and the other carrying a child, which is a sign for the angels taking spirits to heaven. Danzer rightly sums up the message:

The Christ figure assumes the shape of

a dynamic cross, energy bursting forth

from the center. Jesus elevates a

young person with his right hand and

another – it looks like a woman – with

his left, giving them new life. In

response, the skies are filled with

jubilation and the redeemed seem

ready to burst into a song: ‘Our souls

are waking. Our bonds are breaking …

Now and forever. Alleluia’.[#27][27][#27]

Conclusion

Using the technique of wood block printing, and mining a great theme from twelve different quarries in the Luke’s Gospel, Solomon has presented the world a great message of all times – the message of Liberation! This is the need of all times, this side of heaven, and for all diverse people groups of the universe. In depicting the Liberation the Lord gives, Solomon combined his twin instruments of the paintbrush and the pen, and brought out the message in simple but sharp terms. This series of twelve pictures in large original prints are on permanent display in many places in Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, England and the U.S.A. Wood block printing is an ancient art form in Japan, but was popular in Germany also from the time before the invention of the printing press. And as an art form it is now well known and widely practiced all over the world. Solomon explained a brief procedure of this art form in this book. The artist, apart from enjoying his art with his own reflections, longed that “those who look at these pictures will bring out their own reflections in response to these pictures”.[#28][28][#28] His longing has been fulfilled from time to time, as many people in places reflected on different works of this Series. It is a happy surprise when it was fulfilled in plenitude as The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca, Illinois celebrated their centennial with Gerald Danzer’s ‘Meditations for the Twelve Days of Christmas’ through these liberations prints of Solomon Raj, published in 2008.Solomon’s message of liberation will ever remain with us! This study is hoped to refresh many who have seen his art and verse, and for the new generations, who are new to this great contribution, that it would help communicate the richness and beauty of his message, and challenge them to herald this message for those who need liberation in our times.

Dr. David Zersen, President Emeritus of Concordia University, Austin, Texas, who was the former Pastor of The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca did a commendable job in the celebration of this art and this message, most appropriately merging it with the centennial celebration of The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca. It is fitting to note his reflections, as we conclude: The Gospel must be shared in a way that it comes to find a home in your mind and heart, and in the culture of your society. It is the task of the preacher or the poet or the singer or the painter to find the way to allow the Good News about God’s love in Christ to find a patch of ground and to blossom in our lives. When this happens profoundly, the dance or the song or the art that results from it reflects the joy of the life that experiences it.[#29][29][#29] And what an accomplishment for Solomon, as he dedicated his pen and paintbrush just for such a task as this, and what a challenge it is for our generation!

Dr. B.S. Moses Kumar is the Field Superintendent for India for IPHC Ministries, and heads the Hyderabad Bible College as its President. He is a triple graduate holding B.A., B.Ed., and B.D. He holds an M.A. in English Literature and a P.G. Certificate in Teaching of English (PGCTE) from EFL University. He did his M.Th. in Pastoral Theology from University of Wales, and did Ph.D. in English Literature from Agra University. His Doctoral Dissertation (The Religious Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Theological Perspective) was published by ISPCK, Delhi. His ‘Setting Stones: An Interpretive History of the International Pentecostal Holiness Church in India’ was published by LSR Publications, Franklin Springs, Georgia. He is currently doing Ph.D. in Theology with dissertation on ‘Incarnation of the Gospel in Indian Culture with Reference to the Art and Poetry of Pulidindi Solomon Raj’.

References:

- Now We Are Free, The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca, Illinois: 2008.

- Sam Mathew, K. : A Study of Indigenous Symbols in Selected ‘Batik Paintings’ of Pulidindi Solomon Raj as Means of Communicating the Gospel in India (Unpublished Thesis), 2009.

- SolomonRaj, P. : Liberation in Luke’s Gospel, St. Luke’s Lalit Kala Ashram, Vijayawada:1996

- SolomonRaj, P. : Luka Suvarthalo Vimochana Prasakti, St. Luke’s Lalit Kala Ashram, Vijayawada: 2008.

- Scripture Quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are from The Holy Bible: English Standard Version, Crossway Bibles: 2007.

Notes:

[#n1][1][#n1] The color wood block prints in this Paper are reproduced from the Originals made afresh by the artist in 2006 – the whole set preserved in the archives, and copies kept as permanent exhibits at Hyderabad Bible College, Hyderabad. There is a brightness in hue and a slight variation from the original prints of1980’s – but with the same unchanging message. These prints are similar to those published by The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca, Illinois in 2008.

[#n2][2][#n2] Solomon Raj, Liberation in Luke’s Gospel, Vijayawada: St. Luke’s Dalitkala [sic] Ashram, n.d., p. 8.

[#n3][3][#n3] Fr. J. Ubelmesser, S.J. “A Word about the Artist” in Liberation in Luke’s Gospel, p. 6.

[#n4][4][#n4] Now We Are Free, The Lutheran Church of St. Luke, Itasca, Illinois:2008.

[#n5][5][#n5] Sam Amirtham, “Foreword” to Liberation in Luke’s Gospel, p. 5.

[#n6][6][#n6] Ibid.

[#n7][7][#n7] Ubelmesser, op. cit., p. 7.

[#n8][8][#n8] A Study of Indigenous Symbols in Selected ‘Batik Paintings’ of Pulidindi Solomon Raj as Means of Communicating the Gospel in India (Unpublished Thesis), 2009.

[#n9][9][#n9] Luka Suvarthalo Vimochana Prasakti, Vijayawada: 2008, pp. 6-7.

[#n10][10][#n10] op.cit, p. 9.

[#n11][11][#n11] Now We are Free, op. cit., p.7.

[#n12][12][#n12] Jesus begegnet Frauen, München: 2000.

[#n13][13][#n13] Wikipedia: Tandava, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tandava p. 1.

[#n14][14][#n14] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 9.

[#n15][15][#n15] Luka Suvarthalo Vimochana Prasakti, op.cit, p. 11.

[#n16][16][#n16] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 11.

[#n17][17][#n17] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 13.

[#n18][18][#n18] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 15.

[#n19][19][#n19] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 17.

[#n20][20][#n20] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 19.

[#n21][21][#n21] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 21.

[#n22][22][#n22] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 23.

[#n23][23][#n23] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 25.

[#n24][24][#n24] ibid.

[#n25][25][#n25] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 27.

[#n26][26][#n26] ibid.

[#n27][27][#n27] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 29.

[#n28][28][#n28] Liberation in Luke’s Gospel, loc. cit.

[#n29][29][#n29] Now We are Free, op. cit., p. 33.

%20(1).png)