Artists

Kendall, Dinah Roe - by Marleen Hengelaar

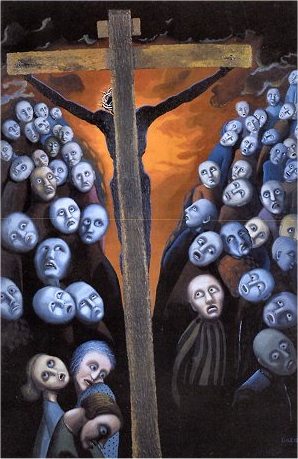

The Moment of Truth

A meditation on the painting ‘The Crucifixion’ (1998) by Dinah Roe Kendall

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

Dinah Roe Kendall: The Crucifixion, 1998

At first sight Dinah Roe Kendall’s painting ‘The Crucifixion’ will probably not appeal to many. Some may even find it repellent. Yet it will prove worthwhile not to divert our eyes away from this scene but to open ourselves for what it has to say to us.

This painting of the crucifixion is by the British artist Dinah Roe Kendall. It in no way resembles the representation of Jesus on the cross we are familiar with. Instead we see the cross from behind and the focus is not so much on the suffering Jesus himself but on the reaction of the bystanders. The picture does not offer us a snapshot of how Golgotha might have looked, but by means of her very own composition and especially by accentuating the faces of the onlookers the artist communicates something to us about the cross. She wields form, colour and contour as a language – a visual language – to articulate her insights in the scene portrayed. We could call this the attainment of twentieth-century art in general: We are no longer bound to a naturalistic representation of the world around us but we can transform reality, abstract it or change its colour in order to all the more clearly convey its meaning. Therefore it is all the more remarkable that the Christian world is often still stuck in naturalistic portrayals for its visual materials, their meaninglessness poorly disguised by a sentimental coating. The pastel coloured blandness pervades your senses when you enter churches and Christian gatherings. But what does a blue-eyed, sweetly smiling Jesus have to do with reality? It makes for a Christian faith that is alienated and other worldly. No wonder many turn away.

Contemporary

In the preface of her book Allegories of Heaven that brings together her paintings about the life of Jesus, the artist writes: ‘I try to remove them from “religious unreality” and endeavour to convey the sense that it could happen at any moment amongst us today!’ She does this not only by distancing herself from unrealistic sentiment, but also by giving the story a contemporary setting. Her ‘Entry into Jerusalem’ for example is situated in the playground of the Porter Croft School in Sheffield (where the painting now hangs) and the baptism of Jesus in a swimming pool.

When we give Dinah Roe Kendall’s biblical images a chance to sink in, it becomes clear that these are powerful representations of the gospel – the product of a faithful heart. She is able to bring the gospels to life because they give her life. We see well thought out and original compositions that compellingly disclose the meaning of the various events. It is particularly striking that all these paintings are full of people. Central to each is how Jesus relates to people and what He means to them. Time and again it is the dramatic gestures and the expressive faces of Jesus and these people, the bright colours and expressionistic style, that tell the story. The artist especially shows great skill in rendering the love of Jesus and the joyful excitement of the people at his presence in a way that remains truthful and therefore all the more convincing. This may well be her greatest merit.

Horror

Because Kendall’s paintings are so human, they are accessible even though she uses a visual language that may not be so familiar to us. Let’s take a closer look at the painting of the crucifixion. What do we see? We see the back of the cross on which Jesus hangs. On either side of the cross stands a multitude of people, their faces accentuated, many of them deathly pale. At the centre of the masses a crimson chasm appears merging into black clouds at the top.

In order to grasp the exact moment that is portrayed here, it helps to take a look at the Bible story. It tells of a great mass of people going along with Jesus to the place of the crucifixion. As soon as Jesus has been nailed to the cross, the bystanders start to mock him: The high priests, the soldiers, even one of the criminals hanging on a cross next to him. They are full of their own self-righteousness. But then all at once, in broad daylight, it becomes dark. The darkness remains for three hours until Jesus dies. Then the earth begins to shake and cracks appear in the rocks. Elsewhere in the city the veil of the temple is torn apart and the dead rise from their graves. That is the instant that is portrayed here – the moment of truth, the very point in time at which people realise that what Jesus said about Himself really was true. In her own comments about this work Kendall says: ‘I wanted to convey the shock and horror at the results of what they had done to him – that is was out of control now, and irreversible. It appeared to them to be a total tragedy and a hopeless loss.’

But let’s read on. The centurion and his soldiers cry out: ‘Truly this was a Son of God.’ And the masses full of sorrow beat their breast as they walk away. But what happens to all these people later on? How many of them ultimately believed in Jesus? Was the number of followers he had in Jerusalem not actually very small? Even some of the disciples had their doubts. And the high priests had ordered soldiers to be stationed by the grave so that the disciples could not remove Jesus’ body. But once Jesus had left the grave these priests paid the soldiers to say that the disciples had stolen his body. They knew the truth but rather preferred to create their own truth! And don’t we find ourselves often doing exactly the same? The devil is not for nothing referred to as the father of lies. We may even witness the crucifixion with our own eyes and seeing not see, unless we open our hearts to the truth. Thus the cross requires us to make a choice. Is this the reason why the cross in this painting creates a division between one half of the mass and the other, forging a deep chasm in humankind as a double-edged sword planted in their midst?

World-shattering

It may do us good to have a painting such as this strategically positioned in our house so that we would walk past it from time to time. Not in the living room because then it may lose its impact as we grow too accustomed to it, just as the powerful reality of grace easily eludes us as a result of its prominent place in doctrine. But it would be good to be occasionally confronted by this painting, to read again the awe and horror in the appalled eyes of the masses near the cross and in so-doing wake ourselves up and recognise once again the immensity of Jesus’ work.

Because what happened here was more preposterous than anything that could ever happen on earth: Jesus is goodness and God personified, but we get rid of him as if he were a murderer. And what happened here had cosmic dimensions that reached further than the effects of any other world-shattering event. The cross after all stands at the very core of history, as it was here that evil was conquered and the way cleared for the redemption and renewal of our world. What happened here was also a greater and more beautiful gift than any I could ever receive. Because thanks to the cross the way is now open for me to live in communion with God and in so doing become a new person. And when I recall all this, the realisation can gradually grow in me that Christ is not just hanging on the cross here with painfully outstretched arms, but that above all he extends them in victory and in blessing.

The painting can be found in the book entitled Allegories of Heaven, Piquant – Carlisle UK, ISBN 1-903689-12-0 / IVP – Downers Grove, Il. USA , ISBN 0-8308-2306-9, 2002. Each painting is supplied with the corresponding Bible passage taken from The Message as well as notes by the artist.

This article appeared in Mel Ahlborn and Ken Arnold (ed.): Visio Divina. A Reader in Faith and Visual Arts, LeaderResources – Leeds, MA, 2009.