Christmas - Kate Rose: Nativity in Perelandra

Kate Rose: Nativity in Perelandra

A Winter’s Tale

by Michael Sadgrove

Kate Rose’s Nativity paintings offer a beautiful accompaniment to our celebration of Christmas.

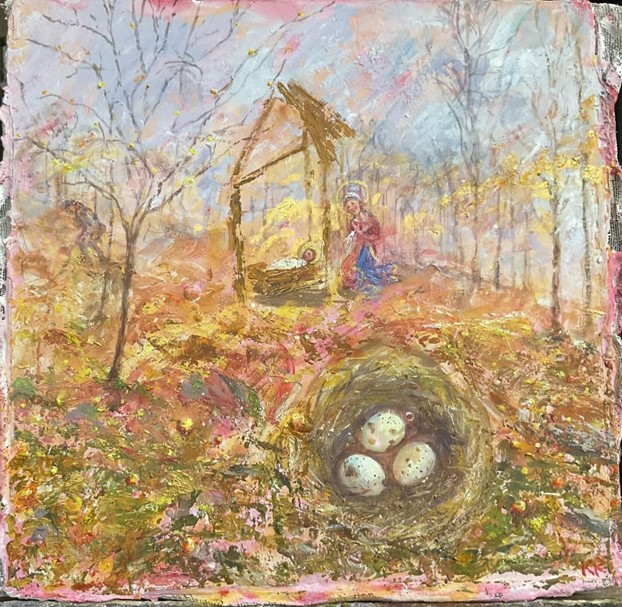

These scenes constitute a winter’s tale. The trees are bare: just a few pink and gold leaves cling on to the branches. The old year, the old world is dying. You sense the exposure in this upland forest, the thinness of the soil, the skeletal rocks beneath your feet, the fierce winds that funnel across these bleak hills.

The forest is an eloquent image of human life. In C. S. Lewis’ Narnia there is a comforting lamp post among the snowy trees, though famously, it’s ‘always winter, never Christmas’. At the opening of Dante’s Divine Comedy, it’s where you are lost ‘in the middle of life’, a dark wood in which you search for direction. In Rose’s forest there are no paths, nothing to signpost us and lead us through this confusing landscape.

Nothing, that is, except the drama that is happening in the midst of it. It begins with Annunciation in which Mary receives the news that she will bear a child. The central panel is entitled Nativity in Perelandra, while the third painting shows The Magi being warned by an Angel in a dream.

In Annunciation (see above) a woman peers out of a tower which, it seems, is her prison. The anchorite cell in which medieval women such as Mother Julian chose to be enclosed for life was an ancient symbol of virginity. Like Tennyson’s Lady of Shalott, she watches what is happening outside. But whereas that unhappy lady was awaiting a curse, this lady, Our Lady, is destined for blessing. It comes in the dove flying down to her, the symbol of the Holy Spirit. What do we read in Mary’s face? Bemusement? Perplexity? “How can this be, since I am a virgin?” (Luke 1:34) Yet an openness too, a willingness to welcome this Visitor and embrace God’s strange work. “Let it be done to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38).

This first panel introduces the motif of the bird’s nest that occurs in all three paintings. Three eggs representing the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. They symbolise birth of course – that of God’s Son who comes amongst us, and the new birth of creation that will follow. And I see them foreshadowing the Easter eggs that stand for the death and resurrection that are the Child’s destiny. The trees are almost stripped bare, but the promise of springtime is already here.

The three eggs are foregrounded again in the Nativity painting. This time they seem to have been joined by a wedding ring. You could so easily miss this tiny detail to the upper right of the top egg. Yet it’s a clue to the entire triptych, for the Incarnation is a cosmic marriage between God and creation, divine and human, “heaven and earth in little space”. The nest leads the eye into the centre of the canvas where Mary kneels by the Infant, as if on the axis around which the world and its history turn. The landscape seems to glow, as if nature is casting its own halo around this sacred drama.

Yet out on the left, a shadowy figure has turned its back on the Nativity and is walking away. It reminds me of Graham Sutherland’s tapestry of Christ in Glory in Coventry Cathedral where the defeated Satan is bundled out of heaven by the Archangel Michael. In C.S. Lewis’ Perelandra of the painting’s title, the Un-man is the negation of the good and the true. But the Incarnation has unmade the Un-man, emptied it of the capacity to do harm. In this landscape of redemption, a new day has already dawned.

The final painting depicts the aftermath of the Epiphany. The Magi have found the Holy Child and paid him homage. Now it is time to return to their own country. The gospel story says that an angel warns them in a dream to travel by a different route, because of King Herod’s vengeful threats.

The painting quotes a beautiful Romanesque sculpture at Autun Cathedral in France. Gislebertus, the 12th-century sculptor, shows the Magi asleep underneath a blanket. (Kate charmingly adds a chamber pot.) The angel hovers above, one hand on the arm of one of the Magi to alert him, the other pointing to the star that will lead them safely home.

The Nativity sheds an afterglow here, particularly in the golden bowl that holds the nest like a crib. Why just a single egg here? Epiphany means manifestation or disclosure. What has been revealed is the mystery of the God who comes among us in Jesus. From now on, the focus of the gospel story will be on him. Like the Magi, we too need to be awakened so that we may go on our way, following the light that has shone into our darkness, the One whom faith recognises as the Light of the World, full of grace and truth.

*******

Kate Rose: Annunciation, 2022, 18 x 27 cm, gesso and acrylic on paper.

Kate Rose: Nativity in Perelandra, 2022, 28 x 28 cm, gesso and acrylic on panel.

Kate Rose: The Magi warned by an Angel in a Dream, 2022, 28 x 28 cm, gesso and acrylic on panel.

Kate Rose (b. 1948) is an British artist who lives and works in Sheffield, UK, with her husband Martin who is also an artist. She trained at Birmingham College of Art where she received a BA in painting and then went on to gain an MA in printmaking from the Royal College of Art in London. Kate has exhibited widely and has work in private and public collections including Sheffield Art Galleries, Sheffield Cathedral, Chelmsford Cathedral, and The Arts Council of Great Britain.

Michael Sadgrove is a retired Church of England priest and a former Dean of Sheffield and Durham. He is a theological educator and writer who describes himself as pilgrim, priest and ponderer.

ArtWay Visual Meditation Christmas 2023