Büttner, Andrea - VM - Aniko Ouweneel-Tóth

Andrea Büttner: Beggars

Attention for Arts and Crafts

by Aniko Ouweneel-Tóth

“God has given me gifts so that I can serve others with them. They are not mine; I received them and share them with others. The others have received different gifts and I, in turn, receive from the others. That is what ‘littleness’ means for me.” This is how a Little Sister of Jesus describes the credo of her convent order in the film Little Sisters: Lunapark Ostia, produced by the German artist Andrea Büttner (b. 1972). Ostia is near Rome, where the sisters live in a fairground and produce their little handicrafts.

‘Littleness’ is one of the pivotal points around which the art of Büttner turns. It does not mean inferiority and certainly not inferior value. ‘Littleness’ stands for a sober, dignified, and serviceable attitude. Büttner uses this notion to approach artistic talent and art.

In an interview she says that working with your hands is a productive way of thinking. In her video What is so terrible about craft? / Die Produkte der Menschlichen Hand (2019, double-channel video) she wonders how manual work can be employed to ‘heal the wounds of modernity.’ How traditional crafts live on and at the same time are changed by modernity, has to do, for example, with political movements, a national narrative, or with religious identity.

Büttner puts her finger on a number of tension-laden problems in contemporary art. Why is craft so often associated with ‘inferior’ art? Why are some forms of art such as woodcuts valued much less than, for example, paintings? How do we relate to a(A)rt? Why are works about poverty not bon ton in the art trade? Why is it almost impossible in the high turn-over popular part of the art market to discuss what else might be of interest? And why do people disdain the use or borrowing of other people’s materials in the visual arts, while learning by heart and declaiming a poem or executing a piece of music composed by others is considered to be true art?

Büttner pleads for a contemporary form of ‘arte povera.’ Hence she does not like to use words like ‘theory,’ ‘practice,’ ‘methodology’ or ‘project.’ According to her, her projects are the same as those of all of us: life itself. Like everybody she collects objects, images, possible subjects and reads and writes about what she considers important, often related to social problems. In order to translate this into works of art, she looks for everything that is valued less in contemporary art: ‘inferior’ materials such as plywood, painting on stones, or the themes of poverty and homelessness.

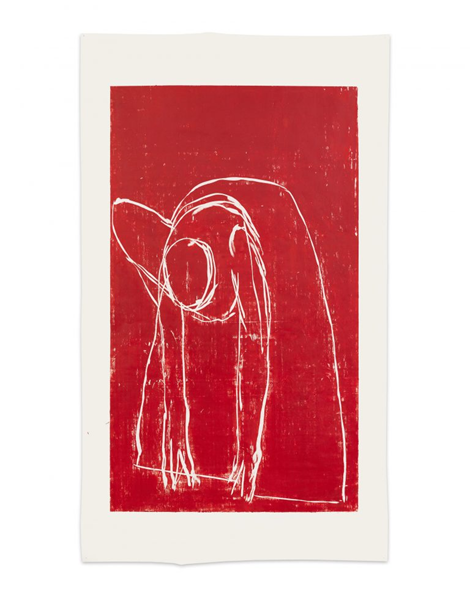

When she started with her wood engravings (metres high!) it was a very old-fashioned medium that was closely associated with the Middle Ages, male artists, and a mediocre hobby-like artistic expression. In this medium she creates fields of colour and rhythm, light and direct. ‘Humility’ receives a positive sound in her work, also because she places it in a Christian context. It is amazing how little has been written in art history about the theme of begging, poverty, or homelessness. In St Francis she found an example of how poverty can be highly appreciated. She also sought to connect with the iconography of the poor shepherds and the rich kings, which she researched in her work Kings and Shepherds.

In her eye-catching series about beggars she also pictures shame by covering their faces. In our culture poverty is shameful. In one of the interviews she tells how making art and being judged by it is also shameful. Laypeople often think that an artist is free to make whatever she desires. Büttner emphasizes how many restrictions she feels and sees and how many moments of self-censure, self-restraint, confusion, and shyness she experiences.

Büttner sees the use of images by others as shopping: choosing and selecting. This practice of appropriation has to do with appreciation and respect, with repetition and learning. She works with what really pleases her. She films subjects that she really loves. This positive attitude is her starting point for detailed analysis and research. Thus the notion of ‘littleness,’ borrowed from the Little Sisters of Jesus, has become an important part of her oeuvre. And lo and behold: receiving a talent as a gift and passing it on, working competently from the heart for others with simple materials, also in the ‘lower’ artistic spheres, turns out to be a gap in the history of art.

In contrast to mass production, digitalisation and the hyped artistic economy of big money, this artist wants to emphasize the power of simplicity and craft. In this way she works towards an about-turn of the hierarchy in the art economy.

*******

1. Photo of the exhibition Andrea Büttner: Gesamtzusammenhang Kunst Halle St Gallen, 2017; Source: https://hollybushgardens.co.uk/artists/andrea-buttner/

2. Woodcut by Andrea Büttner from the exhibition The Displacement Effect Berlin 2021; Source: https://hollybushgardens.co.uk/artists/andrea-buttner/

3. Beggars, 2016, woodcut on paper, various dimensions, installation view, Beggars and I-Phones, Kunsthalle Vienna, Austria, 2016; Source: https://hollybushgardens.co.uk/artists/andrea-buttner/

The most important source for this meditation is this interview with Andrea Büttner: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOnA5mO0qaI

Of interest: Liber Vagatorum (1528, Anonymous, Martin Luther, Editor), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46287/46287-h/46287-h.htm

Andrea Büttner (b. 1972) is a German artist. She works in various media, including woodcuts, reverse glass paintings, sculpture, video and performance. Büttner studied visual arts at the Berlin University of the Arts. From 2003 to 2004 she studied at the Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen and at the Humboldt University in Berlin, where she completed two Master degrees, in Art History and in Philosophy. From 2005 to 2008 she moved to the Royal College of Art in London and completed a doctorate with a dissertation about shame as an aesthetic emotion. Religion is a recurring theme in her work. In 2010 Büttner received the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, presented by the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in collaboration with the Max Mara fashion house. The prize was combined with a scholarship of six months in Italy, which Büttner used to research the artistic practice of Arte Povera (Poor Art). In 2012 Büttner was appointed as professor of drawing at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz. Since 2017 she has been professor of contemporary art at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. In 2017 Büttner was nominated for the Turner Prize. Büttner has written several books, including Shame (König Books, 2020). Büttner lives and works in Berlin. https://www.andreabuettner.com/

Anikó Ouweneel-Tóth is a Dutch/Hungarian author and curator. More info: www.visiodivina.eu

ArtWay Visual Meditation January 23, 2022