Balkenhol, Stephan - VM - Beat Rink

Stephan Balkenhol: Man in Tower

A Firm Foundation?

by Beat Rink

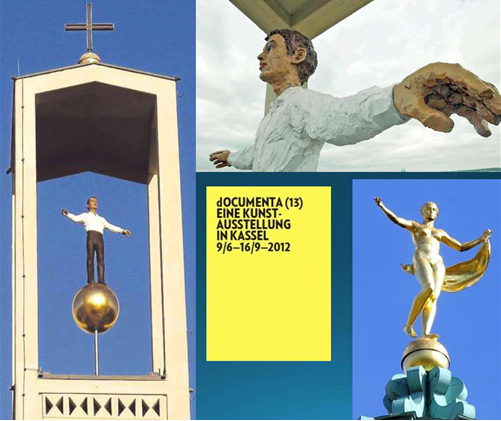

On the occasion of the dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) in Kassel, Germany, the ‘Mecca’ of the modern art scene, the Catholic Church commissioned artist Stephan Balkenhol to create an artistic installation in the St. Elisabeth’s Church. The church is located opposite the exhibition grounds. Balkenhol created large sculptures for the church interior: mainly people in everyday clothing.

In the tower he set up a golden sphere and on it a man with his arms open wide. With this he sparked a huge response. Not only did people call the fire brigade and tell them that someone wanted to jump from the church tower – at which the fire brigade did in fact go into action – but much worse: the management of dOCUMENTA demanded the immediate removal of the figure.

Their main argument: the figure apparently clashed with the concept of the exhibition. dOCUMENTA 13 deliberately wanted to oppose ‘anthropocentrism’, they said. According to the curator, Carolyn Christa-Bakargiev, ‘An attempt is being made not to place human thinking hierarchically over the abilities of other species and things.’ In other words: humans have no special place in the cosmos, but stand on the same level as a dog or a strawberry. The organisers of dOCUMENTA 13 therefore went on to demand democratic structures for strawberries and dogs. Although this sounds humorous, it was meant quite seriously. And for the same reason the protest against the ‘anthropocentrism’ of the church installation was also meant very seriously. But the church did not give way.

But what then is Balkenhol’s message? The artist has made no statement about this. The work deliberately leaves a lot of freedom for interpretation. How can we interpret Balkenhol’s work? Here are a few suggestions:

The man is standing on a sphere. It is like the globe of the world on which Fortuna, the goddess of luck, is often portrayed. Luck is fragile, and so the man is at risk of falling at any moment. But the man appears much more uncertain than the goddess Fortuna, who seems to be saying: ‘Come, try your luck.” The man seems to be saying: ‘How on earth did I get here? I must take care not to fall.’

The sphere and the position of the arms reflect what can be seen on the spire of the church tower: the globe of the world with a cross. The man is imitating the shape of the cross. In 1 Corinthians 11:1 we read: ‘Let us follow the example of Christ!’ The man is doing this somewhat faint-heartedly, but is nevertheless showing courage.

The man (in contrast to Fortuna) is not alone. The church tower and the church (the fellowship of Christians) protect him. And he is under the protection of the cross which is enthroned on the globe of the world. Is this ‘anthropocentrism’? No, it is closer to ‘theocentrism’ – and thus the opposite of the direction taken by the dOCUMENTA 13. But there is one point in which both aims coincide: in calling human dominion into question. Balkenhol was well aware of the ‘God-dimension’. He refused, for example, to remove pews from the church to create more space for his exhibition.

In the wind the sphere turns in every direction. When this happens, the man’s gesture turns into one of blessing – blessing those who curse him, loving his enemies.

In this way the man becomes an imitator, a follower of Christ. The world under his feet sways and turns. He may feel uncertain and be afraid. But he knows this: above me is the cross to which I’m subordinate as well as the whole earth. Thus I stand on firm ground and I can stretch out my hands in blessing.

*******

Stefan Balkenhol: Man in Tower, 2012, Painted aluminium and epoxy, height 200 cm.

Stefan Balkenhol was born in 1957 in Fritzlar, Germany. He now lives and works in Meisenthal, France. Attending the Hamburg School of Fine Arts from 1976-1982, Balkenhol was exposed to the minimalist and conceptual trends popular at that time, with tutors including Nam June Paik and Sigmar Polke. His experience here profoundly affected his subsequent artistic practice. Sensing an absence in these two schools of thought, Balkenhol sought out the human figure and began a campaign to reintroduce it into contemporary art, declaring: ‘I must reinvent the figure to resume an interrupted tradition.’ Balkenhol is recognised not only for the technical prowess with which he carves each of his wooden sculptures, but for his continual devotion to exploring the role of the figure within contemporary art. His figures emanate timelessness: simple, plain-coloured clothing and the poses of everyday man. Balkenhol has developed a significant repertoire of public commissions with installations in front of the Blackfriars Bridge in London, at the entrance of the Hamburg Zoo, at the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, Kassel and Leipzig, Germany. He has exhibited all over the world and his works can be found in collections from Chicago to Venice.

Beat Rink was born in Basel, Switzerland. He has two Master degrees from the University of Basel in literature/history and theology and is an ordained pastor of the Swiss Reformed Church. He co-founded Crescendo (www.crescendo.org) and Arts+ (www.artsplus.ch). He works as a full-time leader of Crescendo international. He gives lectures and has written several books. To read an article by Beat Rink about Christianity and art: in English click here; in German click here.

ArtWay Visual Meditation June 11, 2017