Blake, William - VM - Bill Cross

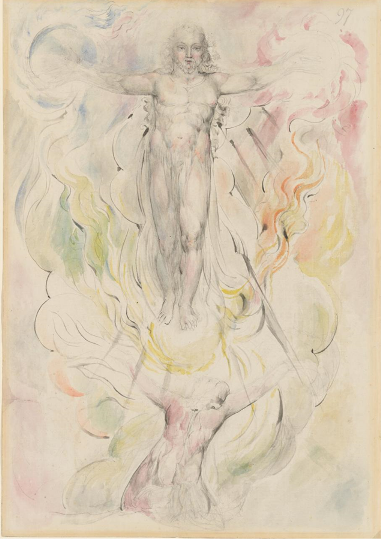

William Blake: Dante Adoring Christ

Beholding the Redeemer

by William R. Cross

The English Romantic painter, printmaker, poet and mystic William Blake (1757-1827) conceived and executed this remarkable drawing-watercolor at the end of his life. It is one of 102 drawings which survive as preparatory studies for a series of engravings he intended to illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy.

The watercolor depicts Dante himself, kneeling at bottom, at a climactic moment in the Paradiso, itself the climax to the Divine Comedy. The poet swoons in adoration before the risen Lord, who stands vibrantly alive, surrounded by clouds, flame and lightning bolts, yet in the cruciform posture of his death.

Here is the text which inspired the painter (Canto XIV, lines 97-111, John Ciardi translation, 1977):

“As, pole to pole, the arch of the Milky Way

so glows, pricked out by greater and lesser stars,

that sages stare, not knowing what to say---

so constellated, deep within that Sphere,

the two rays formed into the holy sign

a circle’s quadrant lines describe. And here

memory outruns my powers. How shall I write

that from that cross there glowed a vision of Christ?

What metaphor is worthy of that sight?

But whoso takes his cross and follows Christ

will pardon me what I leave here unsaid

when he sees that great dawn that rays forth Christ.

From arm to arm, from root to crown of that tree,

bright lamps were moving, crossing and rejoining.

And when they met they glowed more brilliantly.”

Dante seeks to convey a vision of God deeper and broader than the human mind can comprehend, based on the geometry of the cross, encircled and composed of light. In his own ecstatic vision Blake omits the cross (except by inference) and focuses on the person of Christ – the radiant majesty of the ruler of heaven and earth. The painter’s attention is not so much on the celestial landscape as it is on the relationship between the two figures.

Blake is also strikingly emphatic about the face-to-face nature of this encounter. Dante has reached this point on his journey accompanied by Beatrice, who personifies the Church. But Beatrice is not to be seen here; there are no mediators or ecclesiastical intermediaries. Blake places Dante – and by inference the painter himself, and each of us – alone with Christ, awestruck before him, bathed at last in the reflected glory of this singular and unique Lord. And he places Jesus in contrapposto posture, moving with grace towards the writer, and towards the viewer. This Christ is a figure of action, shaped by purpose. What is that purpose? Nothing less than the redemption of all mankind – of Dante, yes, and of me and of you.

And so both men – Blake and Dante – invite us into contemplation of this figure, that we, too, may behold, trust and adore. And just how might that happen? Blake and Dante each believed that the book of nature – the world created by God – provided countless gateways for such meditation. Blake’s famous Augeries of Innocence begins “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour . . .” As the Paradiso continues Dante makes a dramatic shift of scale and focus, finding inspiration in the ordinary and the infinitesimally small. Upon the sight of “bright particles of matter ranging / up, down, aslant, darting or eddying; / longer and shorter; but forever changing,” he breaks into a song of praise to Christ, in joy and exultation. He invites us, indeed all of creation, to speak and to sing of the truth and beauty of its maker, our Savior.

*******

William Blake: Dante Adoring Christ, 1825-1827, pen and ink and watercolor over black chalk, with touches of gum, 52.7 x 37.2 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, Felton Bequest, 1920.

William Blake (1757-1827) was a uniquely multifaceted figure distinguished most of all by the originality of his imagination. He was complex, and would agree heartily with the 1841 statement of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882): “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do.” From the age of four he spoke of powerful, sometimes terrifying, visions. His wife recalled that God “put his head to the window and set [Blake] ascreaming.” By ten he knew that he wanted to be a painter and he began writing poetry at twelve. A five-year apprenticeship with the engraver James Basire taught him the central importance of line. Basire sent him often to draw in evocative settings such as the tombs of Westminster Abbey, which deepened Blake’s appreciation of England’s medieval past, in contrast to the then overwhelming cultural preference for Palladian and other classical precedents. He also developed a profound appreciation for the Bible, primarily as a work of poetry, albeit containing profound truth. He did not take kindly to authority of any sort, including Scriptural authority. So his written, printed and painted works comprise a broad spectrum of penetrating insights into the Biblical narrative, and clouds of confusion.

The death of his younger brother Robert in 1787 was a massive blow to Blake. Nevertheless, the artist found inspiration in the midst of this loss, claiming that in a dream Robert unveiled to him the secrets allowing him to draw directly on copper plates, rather than rely on engravers replicating drawn designs. This technique, relief-etched printing of raised lines on incised plates, was both an artistic and commercial breakthrough, enabling Blake’s integrated control of the entire process. His Songs of Innocence (1789, with 27 plates) and Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794, with 54 plates) put this new “illuminated” technique into practice.

Despite his prodigious creative gifts, his recognized productivity and his wide-ranging friends and patrons, Blake never found a way to make much of a living from his art or his poetry. As he worked with ardor on the Dante watercolors and engravings in his cramped, dark London quarters, Blake succumbed to a noxious mix of Irritable Bowel Disease and two other related illnesses, likely caused or exacerbated by his exposure to the fumes which nitric acid produced as he applied it to his copper plates. Blake was reported to spend one of his last shillings on a new pencil so that he could keep working on his Dante drawings. The day of his death, he laid down his pencil only to sketch his wife, then sing hymns in peaceful readiness to meet the Lord whose glorious face he had spent so many hours imagining and seeking to express in word and image.

For more, see http://www.blakearchive.org.

William R. Cross writes a weekly column on art and the Gospel for his fellow parishioners at Christ Church, Hamilton, Massachusetts, USA.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 11 October, 2015