Rembrandt - VM - Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker 2

Rembrandt: The Risen Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene

The Gardener and his Garden

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

Rembrandt situates Mary Magdalene and Jesus near the opening of the tomb, in close reference to John’s account of the events on this morning of mornings. Mary Magdalene has stayed behind alone at the grave after Peter and John have gone back to Jerusalem. She thinks that the body of Jesus must have been moved to some other place, but which one? She bends over to look inside the tomb and sees two angels sitting there. ‘Why are you weeping?’ they ask her. ‘They have taken away my Lord and I do not know where they have laid him.’ Then she looks around and sees a man standing there, whom she assumes is the gardener.

This is the moment that is depicted in the painting. Mary Magdalene looks up with a glance that is turned inwards. ‘Kyrie,’ ‘Sir,’ she says in Greek, ‘if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him.’ Then Jesus calls her by her name: ‘Mary!’ On her face we see recognition break through, mixed with ‘No, but this can’t be true!’ She recognizes his voice and says ‘Rabboni!,’ ‘Master/teacher,’ in her own familiar Aramaic language. She calls him ‘master,’ as she is indeed one of his disciples, one of the women who went with Jesus and ministered to him and the disciples with their money and care. Then Jesus asks her not to touch him and tells her to go and tell the disciples that he will ascend to the Father. This is why the church fathers gave Mary Magdalene the title of honour of ‘apostle to the apostles.’ She was the first to preach the good news of the resurrection. She was also the first to behold the risen Lord. A woman!

|

|

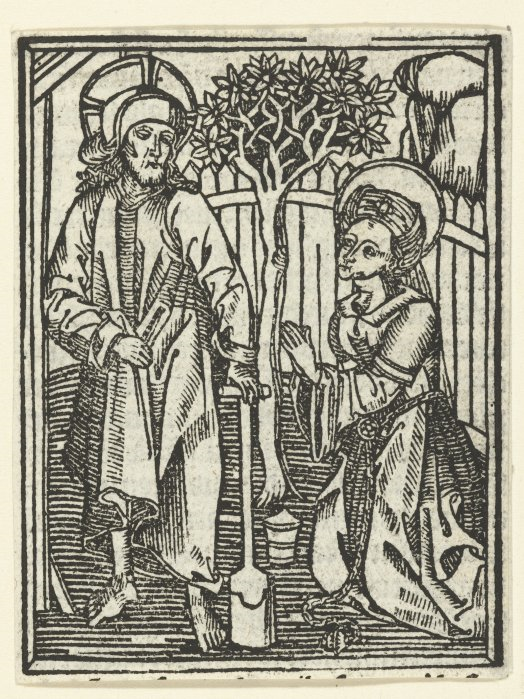

In art history the theme portrayed here is often called Noli me tangere, ‘Do not touch me.’ In works with this theme we therefore see Jesus, depicted as the glorified risen Lord, often recoiling, while Mary Magdalene reaches for him. Here he rather looks at her quietly and attentively, afraid to give her too much of a fright. A beautiful light falls on her face. It does not originate in Jesus, as light from the left falls also on him. It is the light of the rising sun, the vigorous light of a new morning.

Jesus is placed exactly in the middle of Rembrandt’s composition. He is portrayed not as the glorified Lord, but as a sturdy gardener with a large sunhat and a shovel in his hand. Behind Jesus and Mary Magdalene stands a tree. In the foreground we see a garden with a neatly trimmed hedge. In the distance we see Jerusalem in all its glory. Many of these elements are not new or unique to Rembrandt’s rendering of this theme, but are present since the early 15th century when this theme started to develop. Do they remind us of something? Is there a deeper layer of meaning?

To find this out we must first of all return to John 20. This chapter opens as follows: ‘Early on the first day of the week.’ That brings to mind that other first day, that of the creation. Here it is the first day of the recreation. John moreover is the only evangelist who includes the gardener’s incident in his narrative as a subtle allusion to Genesis. In this way Jesus becomes the caretaker and custodian of the garden, the second Adam.

Rembrandt (and the theologians and artists who went before him in this) further elaborate this link with Genesis. The tree behind Jesus and Mary Magdalene refers to the tree which we see behind Adam and Eve in images of the Fall, making them into a new Adam and Eve. The tree becomes the tree of life, the garden of Arimathea the new Garden of Eden. Just as the first Adam was given dominion over the earth, so now the second Adam tends to the earthly garden.

Unique to Rembrandt is the central position of the gardener in this painting, in an active pose, his shovel at the ready. He stands there as the cosmic gardener. In this way Rembrandt puts all the emphasis on Christ as the one who sees to it that his garden flourishes as an earthly paradise, as a place where life is good. Special are the two people on the bottom at the left who stroll along peacefully. This concerns, however, not only the earth here and now, but also the new heaven and earth. In the background we see the new Jerusalem bathe in the light of a new dawn. It is the heavenly garden that Christ is preparing for us.

*******

Rembrandt: The Risen Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene, 1638, oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm. Royal Collection, BuckinghamPalace,London, England.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) was a prolific painter, draftsman and etcher and is regarded as the greatest artist of Holland's Golden Age. He worked first in his native Leiden and, from 1632 onward, in Amsterdam. A crucial aspect of Rembrandt's development was his intense study of people, objects and their surroundings “from life.” Despite the constant evolution of his style, Rembrandt's compelling descriptions of light, space, atmosphere and human situations may be traced back even from his late works to the foundations of his Leiden years. In Amsterdam Rembrandt became a prominent portraitist. The artist became highly successful in the 1630s, when he had several pupils and assistants, started his own art collection and lived the life of a cultivated gentleman, especially in the impressive residence he purchased in 1639 (now the Rembrandt House Museum). In the 1640s Rembrandt's frequently theatrical style of the previous decade gave way to a more contemplative manner. The great group portrait known as The Night Watch, dated 1642 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), could be said to mark the end of Rembrandt's most successful years, but the legend that customer dissatisfaction ruined his reputation is refuted by later commissions from such prominent patrons as Jan Six and the Amsterdam city government.

Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker is Editor-in-Chief of ArtWay.

ArtWay Visual Meditation Easter 2014