Art and the Church -> Materials for Use in Churches

Good Friday - The Crucifixion by Grünewald 2

The Isenheim Altarpiece

From Darkness to Light

by Laurel Gasque

The Isenheim Altarpiece (between 1510-1515) is one of the most famous and also one of the most enigmatic works of art of all time. Even the artist who painted it is really a mystery to us. He is known conveniently as Matthias Grünewald, although this certainly was not his name; he was even confused at times with Albrecht Dürer. Whoever this artist was, possibly Mathis Gothart or Neithardt (c. 1470 –1528), he was filled with exceptional spiritual vision and insight and extraordinary visual expressive power.

The late medieval Isenheim Altar originally stood in the Monastery of St. Anthony at Isenheim. Today, it stands in the Unterlinden Museum (a former Dominican convent) in the town of Colmar (near Isenheim), close to Strasbourg in Alsace in France, not far from the borders of both Germany and Switzerland.

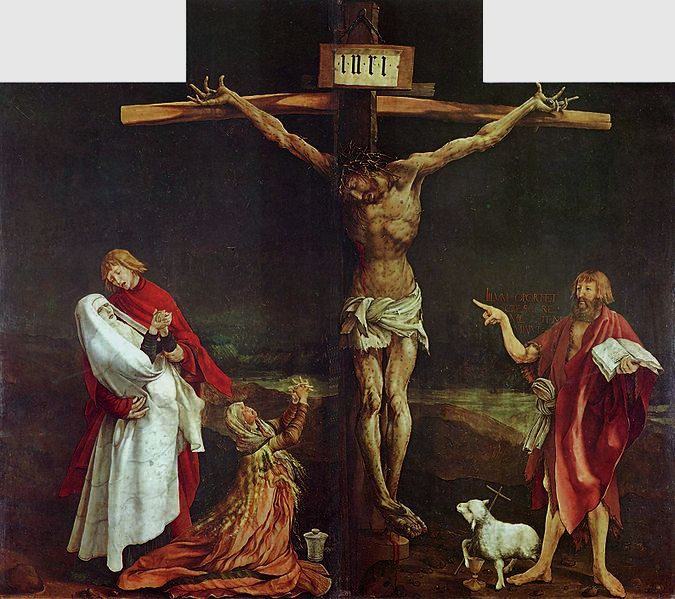

The famous Crucifixion panel is the most remembered and reproduced ‘detail’ of the Isenheim Altar just as the Creation of Adam is of the paintings by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Unless one has been to Colmar or investigated further, most people who see this Crucifixion think it stands alone as a work of art rather than part of a complex altarpiece of many sections and much significance.

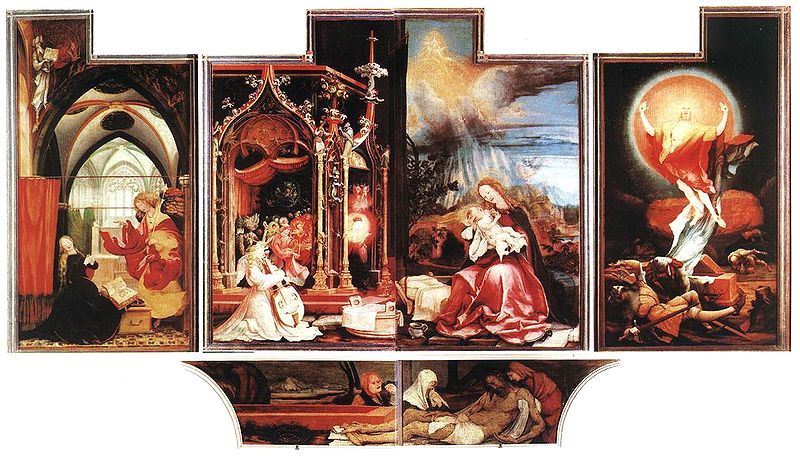

What cannot be shown from this one portion of the whole work is the monumental mingling in it of suffering, sorrow and grief with the glorious hope in and through the resurrected Jesus Christ. The representation of the Crucifixion is in fact two wooden panels that split and swing open to reveal a suite of paintings that are virtually its antithesis. From the black night and doom of the Crucifixion, doors to light are thrust open to reveal the whole sweep of Christ’s life from his birth to his death and resurrection, expressed through a shimmering rainbow-inspired palette of iridescent colours.

In the dark Crucifixion panel, we see Jesus’ identification with our weakness and suffering and his bearing of our sins. The vile eruptions shown on his body are the marks of a disease prevalent in this part of Europe in the late Middle Ages. It was caused by contaminated rye grain that resulted in a wasting of the body and gangrene of the hands and feet. This work originally stood in a hospital ward, as many important altarpieces did at the time, to instruct and encourage the sick and dying. It is not surprising that today an enormous number of AIDS patients take great comfort in this powerful rendering of the crucifixion.

After the Crucifixion section is opened, four scenes appear. Moving from left to right we see: (1) The Annunciation; (2) a scene of an angelic orchestra playing in a beautiful, delicately structured pavilion that transitions to (3) a golden shower from on high, flowing toward Mary with the baby Jesus clutched to her breast swaddled in rags; and then (4) one of the most powerful representations of the risen Christ in all of Western art – the glorious Victor, hands raised, rising above the grave and surrounded by a luminous circular aura with tumbling soldiers beneath him.

Beneath the third panel with Mary holding the infant Jesus we see a horizontal scene in the predella of a blending of the Lamentation and Entombment of Jesus. Three figures from the dark Crucifixion panel, namely the disciple John, the Mother of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, surround the afflicted dead body with anguish and infinite tenderness. Above the lively child lying on a tattered cloth intimates below the Saviour who dies for the sins of the world and who is wrapped in a grave cloth.

The sequence of these scenes succinctly discloses a rich and unique visual expression of the biblical understanding of Jesus Christ’s mission to and for humanity. The four panels depict these events in refreshing ways, from the Annunciation to the Resurrection, unusual for the time in their combination and composition, details and very expressive rendering. The angelic second section, between a diminutive Mary’s encounter with a mighty Archangel (Gabriel) and a more monumental Mary with Jesus clasped close to her bosom (intimating a pietà), encapsulates this unique quality of the altarpiece and remains the most mysterious segment of all.

What does this celestial orchestra mean? One might suggest that the creator of the Isenheim altar was attempting what few artists have probably ever ventured to convey of the sublime virginal conception of Jesus Christ. A conception spoken by the divine Word of the Father, announced throughout the universe by the throbbing dynamic Music of the Spheres by angels orchestrated by the Holy Spirit, to a mere mortal woman, allowing her to bear the Son of God and accordingly enhancing her own lowly stature. Few artists, not to mention theologians, have tried to do this.

Interestingly, Protestant theologians from Philipp Melanchton to Karl Barth have found inspiration from this work because of its profound and inexhaustible biblical and theological meaning.

The Isenheim Altarpiece bears never-ending reflection. Those who live in or visit Europe should definitely make a visit to Colmar or take a group to see it. No reproduction can compare with this extraordinary creation. Embrace this work with your eyes, heart and mind. From the darkest to the brightest of days, this work of art is an incomparable spiritual companion for our consolation and encouragement!

******

Matthias Grünewald (Mathis Gothart or Neithardt): The Isenheim Altarpiece, between 1510-1515, the central part measures 269 x 307 cm; the two side panels are both 232 cm in height and 75 cm in width; the predella is 76 cm in height and 340 cm in width.

Laurel Gasque, associate editor of ArtWay, is author of Art and the Christian Mind: The Life and Work of H.R. Rookmaaker, and Sessional Lecturer in Theology and the Arts at Regent College, Vancouver, B.C. and in Art History at Trinity Western University in Langley, B.C., Canada.

ArtWay Visual Meditation August 29, 2010