Artists

Giacometti, Alberto - VM - Rondall Reynoso

Alberto Giacometti: The Square I

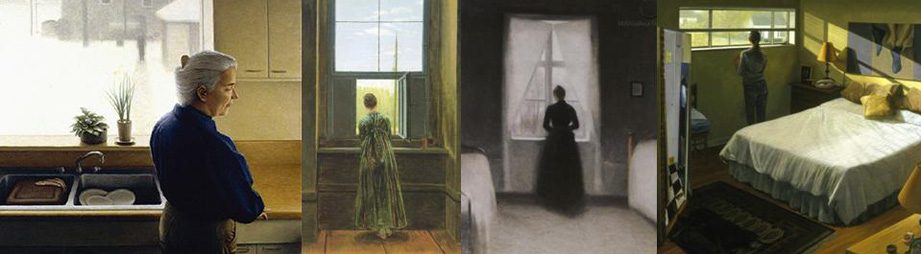

The beauty and loneliness of modern art

By Rondall Reynoso

Despite growing up in a Christian home and studying art in college, I had never read anything about art written by a Christian. Just before graduate school, a friend gave me a copy of Art and the Bible by Francis Schaeffer, the cover of which at that time featured a sculpture of elongated human figures by Alberto Giacometti.

Giacometti might not be a household name, but he’s one of the 20th century’s most important artists. He spent his 20s and early 30s, the years between world wars, embracing Surrealism, but then started feeling disconnected from reality and began returning to depictions of the human figure. By 1935, Giacometti had split with the Surrealists and spent the next few years in intense study of the human head.

During World War II, he took refuge in his homeland, Switzerland. Working from memory, he created sculptures that were typically less than 2½ inches tall. After returning to Paris at the war’s end, Giacometti developed the trademark elongated style that showed up on Schaeffer’s cover.

Art and the Bible profoundly impacted me because Schaeffer provided a Scriptural justification for my interest in art. At the same time, I struggled with his dismissal of much of abstract art. Giacometti’s figures retained some semblance of representational art, so Schaeffer believed they retained their communicative power, but he found a disheartening alienation in these elongated sculptures. “There is a communication between Giacometti and me, a titanic communication. I can understand what he is saying and I cry,” says Schaeffer.

Schaeffer’s reading of Giacometti’s work is not unique. Giacometti’s friend, the French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, said the sculptures reflected France’s post-war spirit of isolation and despair. Influential Christian art historian Hans Rookmaaker saw modern art and life as “tainted” and characterized by “alienation, despair, loneliness, in short, dehumanization.”

Schaeffer, Rookmaaker, Sartre, and many others saw the long, unnatural bodies cast in cold bronze as isolated and isolating—a reflection of our sterile modern existence. Even when grouped, the walking and pointing figures hint at a futile yearning for interaction. In stark white-walled museum galleries, they immortalize eternal loneliness. I can understand why Schaeffer cried.

But when we see these sculptures situated in a sterile context, do we see them as Giacometti saw them? These sculptures were birthed in the artist’s small, cluttered, notoriously dirty studio. Before casting them in bronze, he crafted his images in clay or plaster, obsessing for hours, weeks, and months. Rather than cold, impenetrable metal, these were fragile and earthy.

Giacometti followed the creation of the figures Schaeffer saw as referencing the existential alienation of modern life with 15 years of meticulously studying the heads of a few close friends and family, crafting busts in search of each person’s unique spark.

The unrefined nature of Giacometti’s sculptures is not a failure of skill; rather, the rough textures are integral to what he hoped to communicate. He was exploring the relationship between existence and memory. Perhaps, the bronzes we associate with him are little more than a vague memory, a cold echo of his love for the process of study and creation.

Giacometti’s elongated sculptures are hauntingly beautiful and sad, but they have never made me cry. Instead, I find them strangely comforting. I am under no illusion that he was seeking to make a Christian or even theistic statement with his artwork, but his sculptures reflect the same desperate longing we see in the Book of Job. A longing to make sense of a world that sometimes makes no sense apart from God.

*******

Alberto Giacometti, The Square I, 1960, Bronze, 71,57 x 10,74 x 37,67 in. Image by Stijn Nieuwendijk. Source: Flickr

Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) Alberto Giacometti was born in Borgonovo, Switzerland, and grew up in the nearby town of Stampa. His father, Giovanni, was a Post-Impressionist painter. Alberto’s remarkable career traces the shifting enthusiasms of European art before and after the Second World War. As a Surrealist in the 1930s, he devised innovative sculptural forms, sometimes reminiscent of toys and games. And as an Existentialist after the war, he led the way in creating a style that summed up the philosophy's interests in perception, alienation and anxiety. Although his output extends into painting and drawing, the Swiss-born and Paris-based artist is most famous for his sculpture. And he is perhaps best remembered for his figurative work, which helped make the motif of the suffering human figure a popular symbol of post-war trauma. Source

Rondall Reynoso is an American artist, scholar, and speaker and founder of faithonview.com. He is currently an Assistant Professor at Lee University in Cleveland, TN. He holds an MFA in Painting and an MS in Art History from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY and is completing a Ph.D. in Art History and Aesthetics from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, CA, USA.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 19 January 2025