Maundy Thursday: The Last Supper L. by da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci: The Last Supper

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci

A Tragicomedy

by Wessel Stoker

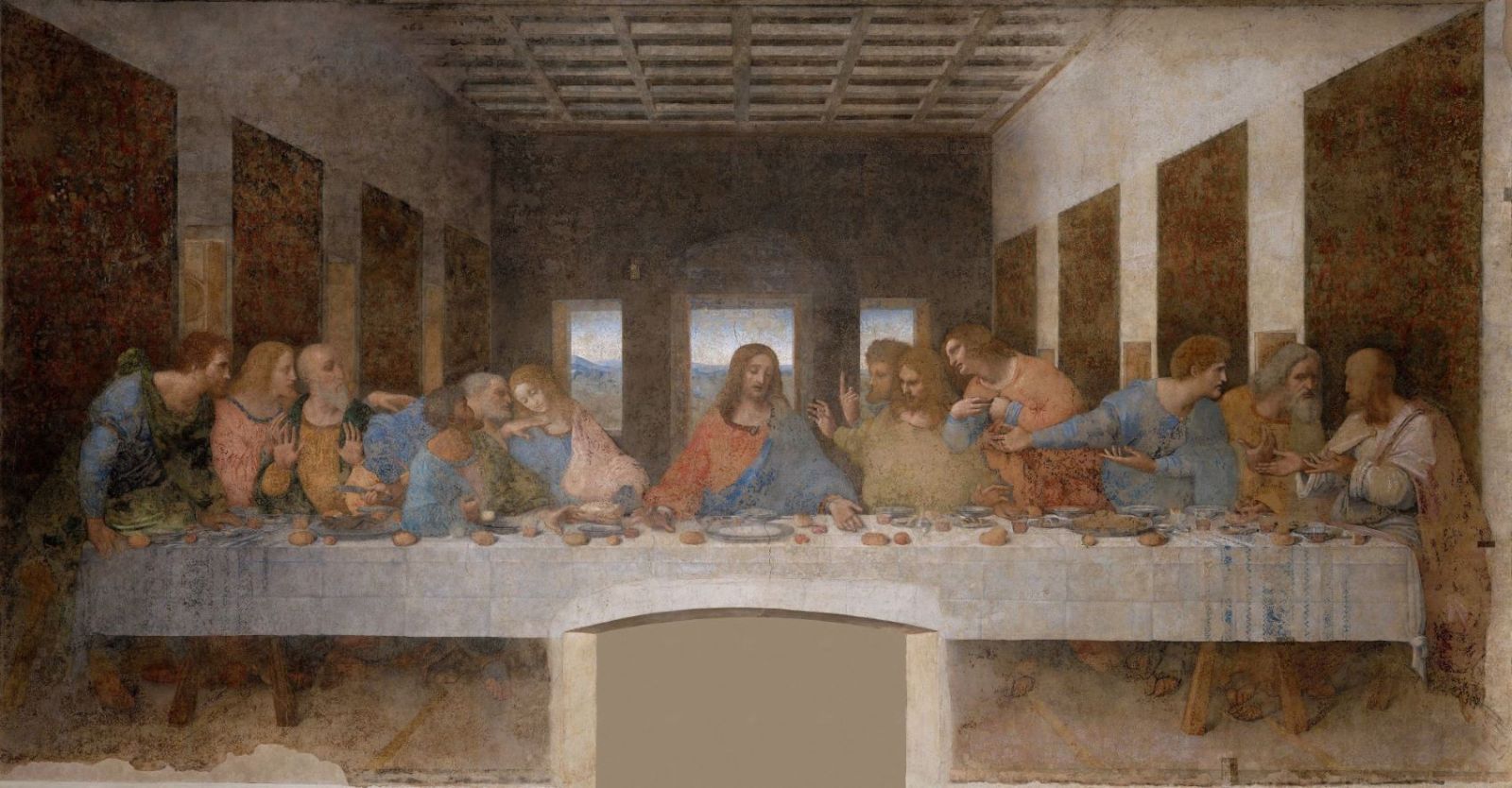

Jesus sits in the middle and radiates a contemplative peace in the expectation of what is to come. His disciples sit on either side of him, gesticulating busily. What did Jesus’ words at the Passover stir up in them that they react so full of emotion?

That evening, Matthew tells, Jesus said to them: ‘Truly I tell you, one of you will betray me’ (26:21). Without a doubt that was a shock. Peter, the second to the right of Jesus (for us the left), motions to John (sitting next to Jesus) with his index finger and says, ‘Ask him which one he means’ (John 13:23-24). Andrew, the fourth to the right of Jesus, lifts both hands half-way up as if to say: ‘Surely, that is not going to happen?’

When they continued to eat, Jesus gave thanks for the food, he broke the bread, and gave it to his disciples, saying: ‘Take, eat, this is my body.’ Likewise, he then took the cup, saying: ‘Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.’ The disciples would have wondered about these words. To the left of Jesus at the end of the table it looks like Matthew, Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot are discussing this with one another. Philip, third to the left of Jesus, points with both hands to himself. Does he mean to say: allow me to make that sacrifice? It is a meal full of drama.

Leonardo’s work is not a fresco. He used a different technique and different paint for his wall painting in the refectory of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery in Milan. If it had been a fresco, then it would have had to be made in a very short period of time. However, according to eyewitnesses, Leonardo worked on it from morning to night. He often left the work for some time and returned to it a few days later to resume working on it. Sometimes he looked at it for one or two hours and then changed something.

Judas’ betrayal is closely connected with Jesus’ words about his body and blood of which his disciples may partake. They are two sides of one story. The evangelists tell their account in words, whereby both events are told one after the other. The visual language provides something extra here. Da Vinci weaves both events into one picture, as if it is one event with two aspects. His wall painting gives an additional layer of meaning to the biblical story.

Look at Jesus’ arms and hands. Matthew relates: ‘The one who has dipped his hand into the bowl with me will betray me’ (26:23). The third to the right of Jesus is Judas. He holds the money bag with his right hand, his left hand reaches for the bread, while Jesus’ right hand also reaches for it. On the wall painting this happens at the same time as that other moment. With his opened left hand Jesus points invitingly to the bread, as if saying: ‘Take, eat, this is my body.’

However, Leonardo brings yet another, deeper layer to his Last Supper. It is possible that he does that because of what he had read in John’s Gospel, where Jesus speaks about his death: ‘When he [Judas] was gone, Jesus said, “Now the Son of Man is glorified, and God is glorified in him”’ (John 13:31). In this way John puts this event in a divine light. Leonardo depicts this aspect by bringing out Jesus’ divinity. It is a Christophany: an appearance of Christ as Son of God. It is in three ways that Leonardo brings this out.

Jesus is rendered larger than his disciples and we see him full in the face, whereas we only see the disciples in profile. I see Jesus’ posture, with his shoulders and arms down a bit, as an expression of surrender to what will happen to him. His upper torso is presented as a triangle. I interpret that as an allusion to the Trinity: Father, Son, and Spirit. Furthermore, the number three is present in the way the disciples are grouped in threes to the left and right of Jesus.

In addition Jesus is separated from his disciples, even from John, ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’ (John 13:23). In contrast to how John’s Gospel tells it, we do not see John leaning against the bosom of Jesus. In other representations this is how it is portrayed, for example in this print by Albrecht Dürer.

In Leonardo’s work, at this moment when all the attention is on the divinity of Jesus, there is a distance between Jesus and his disciples. The moment of epiphany requires Jesus to sit apart. Something else is notable. The room in which the event takes place has a sacred character. Leonardo da Vinci, who also was a mathematician, plays with perspective in his painting. The whole manner of staging the room is intended to bring the table with Jesus to the front. The two side walls are shortened, so that the room looks smaller. This means that the attention of the viewer is completely directed towards the table with Jesus and his disciples. Moreover, you can see that both side walls run parallel with both of Jesus’ arms. The room is sanctified, as it were, by the event.

Leonardo da Vinci presents the event of the Last Supper in a very intense manner. He has an eye for the human and tragic aspect, the betrayal of Judas, but also for the divinity of Jesus: ‘Now the Son of Man is glorified, and God is glorified in him.’ It is a tragicomedy: an event that initially occurs as a tragedy but has a good ending. Leonardo shows us impressively the tragicomedy of him who made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And that is why God has highly exalted him.

*******

Leonardo da Vinci: The Last Supper, 1495–1498, distemper, gesso, mastic, pitch, 4.6 x 8.8 m. Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan., Italy.

Albrecht Dürer: The Last Supper, 1511, print, 39.4 x 28.3 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was architect, inventor, engineer, philosopher, physicist, chemist, anatomist, sculptor, author, and painter in the Florentine Republic during the Italian Renaissance. He is regarded as the textbook example of the Renaissance ideal of the homo universalis.

Wessel Stoker is emeritus professor in theological aesthetics, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Literature:

D. Arasse, Leonardo da Vinci, Cologne: Dumont 1999.

L. Steinberg, Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper, New York: Zone Books 2001.

M. Kemp, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 2 April 2023