Ervin Bossanyi: A vision for unity and harmony

Ervin Bossanyi: A vision for unity and harmony

by Jonathan Evens

Ervin Bossanyi (1891-1975) wrote of belonging in spirit to a “universal church” as he recognised the “profound inspiration” of all the great religions, possessed a “reverence for life,” and longed for a “new cosmopolitan world order, in which ideological, racist, and cultural differences no longer mattered.” In his life and art, he fused influences from Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism and Sufism to create a vision of harmonious, unified human societies that were at one with the natural world. This is a profound and profoundly moving vision of life based both on his experience of peasant life in Hungary and the influence of the art of non-European civilisations. It was a vision forged in a time of great conflict and division which had significant personal impact for Bossanyi and his Jewish family. It is a vision that we desperately need to regain in our time, where similar divides and conflicts have re-emerged and where the kind of forced migration that so impacted Bossanyi, his family and career, affects huge numbers of those that are among the poorest and most disadvantaged within our world.

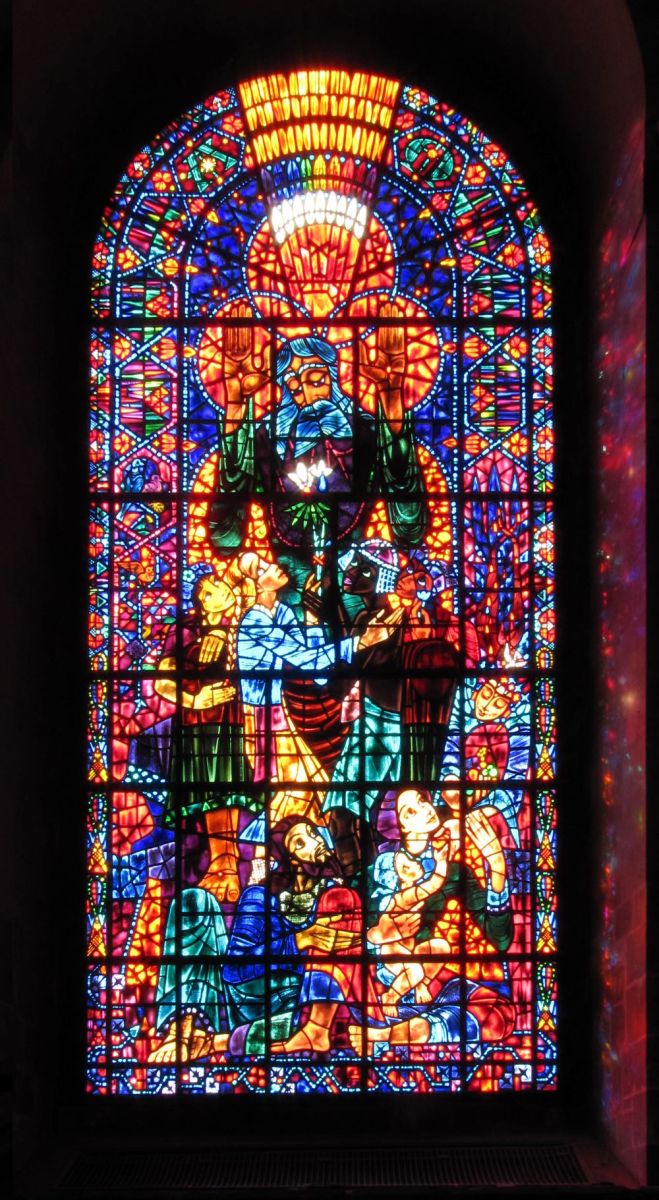

Ervin Bossanyi: Peace and Freedom window for Canterbury Cathedral, 1956, detail

In this article I briefly map out the context within which Bossanyi’s work and vision can best be understood and appreciated, by showing the extent to which aspects of his approaches were shared with others in his day and time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were several examples of Arts and Crafts colonies or movements within Europe which had strong stylistic and philosophical affinities to the work of William Morris, John Ruskin, and their followers in Britain. The Gödöllo artists’ colony in Hungary founded by Aladár Körösfoi-Kriesch and his brother-in-law Sándor Nagy in 1901 was one such. Jo Bossanyi and Sarah Brown have noted that this group gained “semi-official status in the pre-1914 period as the foremost representatives of Hungary’s new national style;” one “based traditions handed down from past ages” including folk art and a wide variety of applied arts.

At the School of Applied Arts in Budapest, Bossanyi gained a solid grounding in the skills required for his own versatile career which covered ceramic painting, murals, painting, sculpture, and stained glass. Work by “the Gödöllo artists and craftworkers would certainly have been known to Bossanyi, furnishing a potential exemplar to the young student of applied art.” The group were profoundly influenced by Magyar folk art but also drew on “motifs derived from Indian and other non-European cultures.” The Gödöllõ artists also painted symbolic religious frescoes for churches in Hungary.

Bossanyi lived in Paris at points between 1910 and 1914, generally with his friend Imre Szobotka and his compatriot József Csáky. While there, he came under the influence of the Sufi philosopher, poet and musician Hazrat Inayat Khan for whom he created illustrations to his poems. These are now lost to us and a similar fate befell a later interfaith project with Eastern origins, the Shivaji project for Aundh in India.

Bossanyi’s time in Paris coincided with the period in which Cubism was first developed, a time and place from which artists such as Marc Chagall, Albert Gleizes, and Gino Severini would develop spiritual uses for cubist discoveries.

Bossanyi, with Szobotka, drew these innovations into his own spiritual work in the watercolours created while they were interned in France during the First World War. These were inspired by the Catholic spirituality of Paul Claudel’s four-act play L'Annonce faite à Marie.

Following the First World War, Bossanyi settled in Germany where Expressionism completed the main influences on his personal vision and approaches. In Lübeck he received support from the art historian Carl George Heise, who promoted the work of Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, Ernst Barlach, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, among others. In 1921 Heise organised a retrospective of Nolde’s religious paintings at the Katherinekirche, a museum church. Through these and other artists including Bossanyi, Hiese sought a “spiritual revolution” providing “meaning and direction in the politically fragmented post-war epoch.”

It was not just in Germany that such a spiritual revolution was being sought. The French Catholic Revival saw artists such as Maurice Denis and Georges Rouault develop international reputations, with Denis influencing artists in Belgium, Italy, Russia and Switzerland as well as France. In Britain Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill were among those revolutionising sculpture and doing so by exploring religious themes. As the Second World War approached and then in the reconstruction following, there was a significant focus on Christ’s crucifixion as a means of depicting the horror of war and genocide – Francis Bacon, Romare Bearden, Abraham Rattner, F.N. Souza, Graham Sutherland – with the Church then offering many new commissions as existing churches were repaired and new churches built.

Ervin Bossanyi: Peace and Freedom window for Canterbury Cathedral, 1956

Bossanyi’s church commissions were slightly later in arriving, but he had sought support at an earlier stage from those involved in encouraging such commissions, including George Bell, Bishop of Chichester.

Bossanyi left Germany for Britain prior to the Second World War, aware that both his family and work would be under threat had he stayed. He therefore joined the large number of émigré artists arriving in Britain, many of whom were Jewish, many of whom explored spirituality within their work, and many of whom would, like Bossanyi, receive church commissions in the post-War period. Among his peers in some of these respects were the muralist Hans Feibusch, mosaicist Georg Mayer-Marten, sculptor Ernst Müller-Blensdorf, ceramicist Adam Kossowski, and painter Marian Bohusz-Szyszko.

Ernst Blensdorf: Annunciation, 1957

In 1940 Blensdorf wrote of an “ever-increasing number of people who are determined that out of this war permanent peace shall come for all mankind.” Declared a degenerate artist by the Nazis, who ordered all his work to be destroyed, he migrated first to Norway. Deeply moved by the human suffering he had witnessed he conceived the idea of an “International Nansen Monument” to promote peace and encourage human rights. But as work on the project was about to begin, Norway was invaded and Blensdorf fled to Britain. Once settled here, he set about reworking the project but eventually was forced to drop the project and use his experiences of sacrifice and resurrection to inform the sculptures Abraham’s Sacrifice and Resurrection Christ. These were Blensdorf’s equivalents to Bossanyi’s Peace and Freedom windows for Canterbury Cathedral.

Many of those creating work for churches in this period were Jewish. While this reflected economic necessity, it also demonstrated a concern within the Church for those who had suffered and, on the part of Jewish artists, “a way of building bridges, of forging links, of creating dialogue between Jews and Christians.” This seemed to many more necessary than ever in the wake of the war. Like Bossanyi, who recognised the “profound inspiration” of all the great religions, Marc Chagall was to create the first of many commissions for a Christian church “In the name of the liberty of all religions.”

This, then, is the context in which Bossanyi’s work and vision needs to be placed in order to be understood and appreciated as a unique contribution to the spiritual and religious art created in this period and one having synergies with the work of his peers. In Europe and the United States this was a time of a modernist preoccupation with religion and spirituality to which Bossanyi and other émigré artists made an immense contribution, despite the challenges they faced through enforced migration and the loss of work. Bossanyi contributed a vision for unity and harmony embracing all peoples and all faiths whilst being based on the fundamental interactions of human life. As Rowan LeCompte wrote in his obituary appreciation, Bossanyi possessed a “poetic sensibility” that was combined with “tender dreams” and set them both “into that unlikely place, church windows – which is where they truly belong, but in our embarrassed and commercial age hardly ever are found.”