Joseph Beuys: A Spiritual German Artist

JOSEPH BEUYS: A SPIRITUAL GERMAN ARTIST

AN IMPRESSION

by Wessel Stoker

Last year (2021) was the centenary of the birth of Joseph Beuys (1921-1986). He was commemorated in many places. He was especially known for his performances, display cases and installations, but also for his teaching as professor at the Academy of the Arts in Düsseldorf, as well as his speeches and interviews. But what kind of artist is he? About that opinions vary. Is he first and foremost the German artist who put German art on the map again after World War II? Is he the artist who made political art to benefit a green, liveable earth? Is he the German artist whose work is also the processing of mourning for the Holocaust? Is he the spiritual artist who was inspired by the person of Christ, thanks especially to Rudolf Steiner? He is all of that. It becomes even more complex when you look at his (auto)biographical details. He hesitated about studying natural sciences[1] but in the end chose art and registered in 1947 as student at the Academy of the Arts of Düsseldorf. What role did his rescue by Tartar tribesmen play in his art after his plane was brought down in 1944 by the Russians in the Crimea? Is there a thread that connects the multifaceted work of this artist? My hypothesis is that Beuys’ spirituality is what drives his diverse work.

A German Artist after Nazism

How can there be art after Auschwitz? This question can be understood in different ways. Factually: how can art be produced again in Germany after the anti-modern art campaign of Nazism? Or as regards content, with reference to the well-known saying by Adorno, ‘After Auschwitz it is barbaric to write a poem’: is art made with the memory of Auschwitz even possible? About the first, briefly, after the war there was a need for a trailblazer, a theoretically grounded artist who would be able to put German art back on the map. Could that be Beuys? According to Pamela Kort, he seems to hint at that in his Lebenslauf/Werklauf (Life Course/Work Course). By1946 (one year before he began his study at the Academy of the Arts) he wrote: ‘Kleve Künstlerbund “Profil Nachfolger”’ (Kleve Artist Association “Profile of a Successor”). He repeated that in 1950 and by 1955 he stated: ‘Ende von Künstlerbund “Profil Nachfolger”’ (The End of the Artist Association “Profile of a Successor”).[2] For him this was a time of deep depression. He probably no longer saw himself as ‘successor’ during his crisis of those years. However that may be, from 1961 Beuys did get his forum through his professorship at the Art Academy. As Kort wrote: ‘The way was now open for him to become the long-awaited successor who could revive culture in Germany and lead a younger generation of artists to distinction.’[3] Towards the end of 1979, Beuys was the first German to have an exhibition in the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

A Political Artist

As an artist Beuys chose sculpture rather than painting, which he thought to be too illusory. Sculpture, with its three-dimensionality, is realistic and spatial. But he added something to that. He preferred to speak about his work as Plastik, as the activity of shaping something, derived from the Greek word plastikos (able to be shaped; plassein: to shape, to knead). He interpreted that broadly. In his Lehmbruckrede (1986) he spoke approvingly about the German sculptor Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919): ‘… in ihm wird die Plastik nicht mehr nur das rein Räumliche, das Raumausgreifende, der Organismus des “Mass gegen Mass”’. (In him Plastik is no longer purely spatial, that which takes up space, the organism of “mass against mass”).[4] His sculptures also express something internal, that is to say, ‘seine Skulpturen sind eigentlich gar nicht visuell zu erfassen.’ (His sculptures cannot really be comprehended visually at all). He continues: ‘Als ich an ein plastisches Gestalten dachte, das nicht nur physisches Material ergreift, sondern auch seelisches Material ergreifen kann, wurde ich zu der Idee der sozialen Plastik regelrecht getrieben.’ (When I thought of a sculptural shape that doesn’t just consist of physical material, but can also consist of spiritual material, I was driven directly to the idea of social sculpture). His own art as sociale Plastik involves therefore much more than giving shape to natural materials. According to his ‘extended concept of art’ (der erweiterte Kunstbegriff) ‘every person is an artist.’ Beuys already calls a thought arising out of creativity a work of art, a sculpture. Art as social Plastik aims to transform society. Each person as artist must participate in the transformation of society.[5]

For his theory of art as sociale Plastik he made use of Rudolph Steiner’s theory of society, his concept of a threefold social organism. In light of this Beuys strove towards liberty in the sphere of culture, equality before the law, and solidarity in economy.[6] He saw human society interwoven with the natural world. Inspired by Steiner’s lectures Über die Bienen (About the Bees) dating from 1923, he saw an analogy between a colony of bees and human society.[7] The world consists of mutual coherences, humans and nature are interwoven. There is also a force of moral-spiritual growth thanks to the impulse of Christ. I will return to this.

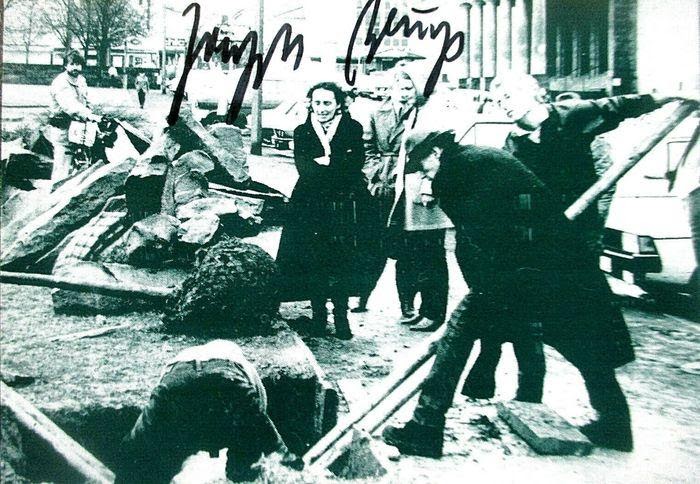

With his political views Beuys stood at the cradle of the origin of the Green Party. He did not speak about his activities as politics. ‘I only know art,’ which he however conceived of in line with his extended concept of art, which aims to determine our being and acting primarily by art in the sense of the liberation of all creative powers.[8] For example, he raised the ecological question of the interwovenness of humanity and the natural world in his ‘Aktion’ of the 7000 oak trees on Documenta VII in Kassel (1982).

He placed an oak together with a stone of 1.20 m. The tree, in contrast with a stone, knows growth and movement. The stone represents the status quo and the tree represents the desired creative process. Beuys showed how people blocked a green future with their technology, materialism, production processes and political strategy. The 7000 oaks represent the start of a process of correction and revitalisation, not only of nature, but also of society, the social organism. The 7000 trees are planted in Kassel, although they did not all turn out to be oaks. This ecological art (Plastik) is an impressive testimony of Beuys’ broad concept of sculpture as soziale Plastik.

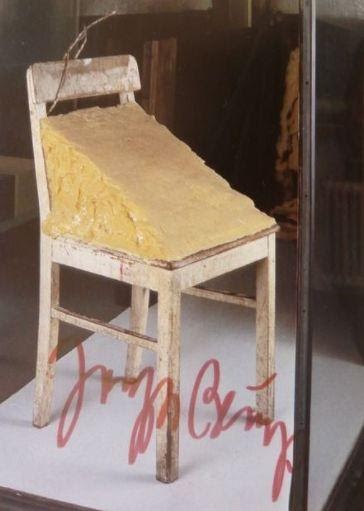

Art of the Mourning of the Holocaust

It is well-known that Beuys often worked with felt and fat. You can see him on Youtube in his Aktion I like America and America likes Me (1974) dressed in a felt coat with a coyote locked in a cage in a gallery in New York. The coyote is a sacred animal for the native population of America but became a prey for the Westerner. Was Beuys – who had been a great friend of animals since his youth – going to be successful in restoring the relationship with the animal? This use of felt goes back to the story of his rescue by the Tartars who, he claimed, saved his life when he was seriously wounded after his plane had crashed, by wrapping him in felt and salving his wounds with animal fat.[9] He also often used fat, as for example in Stuhl mit Fett (1963), a kitchen chair liberally stacked with fat and a steel thread. In the version of 1985 the steel thread is missing, and a thermometer is stuck in the fat. In his explanation Beuys points to the malleability of fat, dependent on the temperature. With this art object Beuys wants to initiate a discussion about creativity.[10] After all, fat is a carrier of energy that in a cold environment is malleable and becomes liquid in warmth, thereby dissolving the shapes.

Gene Ray is of the opinion that his use of felt and fat in some of his works can also have a different meaning and can refer to the Holocaust. The project sociale Plastik was directed at the future. But how does he process the past, the wartime when he served with the German air force, in his art? Beuys was twelve years old when Hitler came to power and became a member of the Hitlerjugend and later served in the German air force. It is difficult to say when he came to know about the Holocaust, in any case after the war. He must have known about the human fat of the victims that was released during the burning and was saved for use in the extermination ovens to make them burn more efficiently; just like the use of the victims’ hair, which the Nazis used to make felt and processed into slippers or socks.

Reading Beuys’ biography by Stachelhaus I deduce that he did not subscribe to the Nazi-ideology. When he was interviewed by the brothers Van der Grinten in 1961 about his most important war-time memories, he only talked about the many places in Europe where he had been as a soldier but said nothing about National-Socialism.[11] Beuys repeatedly escaped from life-threatening situations during his service in the German air force and came out of the war a bodily wreck. Surely, he cannot keep quiet in his art about this German past? Gene Ray wants to look at the works of art themselves, apart from the artist’s explanation. That is certainly hermeneutically legitimate. In this way some of the works can be explained as ‘a mourning process’.

A clear allusion to the Holocaust is for example his submissions for a design of an Auschwitz monument, Wettbewerbsentwürf für Mahnmal in Auschwitz (1957).[12] The objects in the display case Auschwitz Demonstration (1950-1964) refer to life in the camp, such as the last meal in the concentration camp (KZ=Essen 1, KZ=Essen 2, 1963). Ray also points to Beuys’ Aktion Kukei, akopee, Nein! … a performance on July 20, 1964 in Aachen. The Aktion begins with the rhetorical question from Joseph Goebbels’ speech of 1943 in the sport palace in Berlin: ‘Do you want the total war?’ In this ritual Beuys showed a number of objects, such as a portable cooker with two burners with which he imitated the heat of fire. He melted several pieces of fat and warmed a zinc chest for fat. He acted this performance on the twentieth anniversary of the failed assassination attempt on Hitler, and seems to refer, according to Ray, to the crematoria of the Holocaust, where during the burning the fat from the corpses was released and re-used during the next burning. Fat and felt, which according to his Crimea-story are essential for life, acquire here a totally different and gruesome meaning.[13]

Is it possible to make art in memory of Auschwitz? Beuys does that in his works of grieving and in his sociale Plastik project. He renders what is inconceivable by way of a ‘negative presentation’. He only shows the personal traces of the victims: the victims are remembered in their absence, just as Boltanski often does in his memorial art. The fat on the seat of the Stuhl mit Fett conjures up, according to Ray, an absent figure like a ghostly afterimage.[14]

A Spiritual Artist

Beuys is the artist who put German art on the international map after the World War II. He replaces the traditional concept of art with his ‘extended concept of art,’ the sociale Plastik directed towards the future of a transformed society. He also looks back to the German past and offers memorial art. What is the connecting link in this diversity? Central is the giving shape (gestalten) in a material and spiritual sense. I point to the quotation cited above from his Lehmbruckrede: ‘Als ich an ein plastisches Gestalten dachte, das nicht nur physisches Material ergreift, sondern auch seelisches Material ergreifen kann, wurde ich zu der Idee der sozialen Plastik regelrecht getrieben.’ (When I thought of a sculptural shape that doesn’t just consist of physical material, but can also consist of spiritual material, I was driven directly to the idea of sociale Plastik). With that, his vision of art is aptly expressed as giving shape to both the externality of society as well as the inner self of the human being. But what motivates him in his sociale Plastik?

At Beuys’ exhibition Menschenbild-Christusbild in 1984 in the St. Mark’s Church in Nied, Frankfurt am Main, journalist Elisabeth Pfister asked him what he thought of Rev. Friedhelm Mennekes placing his work in the Christian tradition. His answer was that it did not disturb him at all: ‘The idea of the individual is inseparably fused with that of Christ. In that respect, you cannot think of people without Christ’ (81).[15] In the period of 1947-1960 he used Christian symbolism in his art. His Sonnenkreuz (1947/8) is a beautiful example of this symbolism.

The bronze sculpture is a crucifix, a cross without crossbeams. Christ’s arms – or is it a human being in general? – stretch upwards in the shape of a V with a radiant sun that seems to turn between his arms above his head. The head is crowned with a wreath of vine leaves. It makes you think of Jesus’ words about the vine and the branches (John 15:5), but it could also refer to a representation of Dionysius, who was the Greek god of fertility, ecstasy, and life. The Sonnenkreuz expresses a contrast between life and death, between the sun and the hanging corpse. Death and resurrection are pictured here in one. The sun above the cross can point to Beuys’ cosmological Christology, his striving for a connection of Christ with the powers of nature (204).[16]

Beuys made a wide range of variations on the cross and, although he did not explicitly use Christian symbolism after 1960, the cross as part of culture remains present in his art (84). He sees Christ as the model of humanity: the cross and resurrection play a part in every human life. It is through the resurrection that Beuys looks at Christ’s suffering and cross: ‘And the tone [of Jesus] in which he speaks and the healings as they are carried out signify this tone of certainty of the end or the beginning; for the end of this Passion is naturally a beginning. In death there is life. That is the mystery of the Son of Man. Proper life comes only then’ (54, 56). I see Christ’s stretched out arms – or of humans in general – of the Sonnenkreuz in the shape of the ‘V’ as the well-known gesture of Churchill, the ‘V’ of Victory. Beuys is not concerned with Christ from the past, but with Christ after his resurrection as a continuing power in the world, the impulse of Christ in each person. Everybody needs to go through a process from death to resurrection:

You must first lose your faith as Christ did for a moment on the cross. That means that the individual also has to suffer the Crucifixion and the full incarnation in the material world by working right through materialism. He must die and he must be completely abandoned by God as Christ was left by his Father in this mystery. Only when nothing is left, does one discover the Christian substance through self-realisation and accept it as true (32, 34).

Jesus’ story offers a perspective for this self-realisation because it shows that life comes forth from death, the dying kernel of wheat that produces many seeds (John 12:24). The same applies to every person according to Beuys: he lives amongst the dead, that is a lonely situation through which the person must go in order to arrive at his resurrection (56, 8). Real life comes about through death. His Christology implies self-discipline, which he admired so much in Ignatius of Loyola and his Spiritual Exercises. According to him there is no other possibility for the individual than to take on themselves the role of Christ. In this way, Christ lives in each person:

For I start with the assumption that a higher form of man has come into existence … that this came to be so tangible, then also included in this message that Christ lives on in every human being. Whether I wish it to be so or not, the essence of Christ exists within me as in every other person. So one can also say, each human activity is accompanied by this higher I, in which Christ dwells (86).

In his own way Beuys, inspired by Steiner, used Paul’s insights such as his word: ‘If we have been united with him in his death, we will certainly also be united with him in his resurrection’ (Romans 6:5) and ‘I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me’ (Galatians 2:20). In his rejection of a doctrinal church, art is for him the way to spiritual life as sketched here. That is why the young Beuys chose to attend the art academy and developed his concept of art as sociale Plastik, thanks to which not only the individual but also the German population can conquer their ‘schrecklichen Sünden, nicht zu beschreibenden schwarzen Male.’ (terrible sins, indescribable black marks).[17]

Beuys’ concept of art and his opinion of Christ come together in the concept of creativity, already discussed. According to his extended concept of art, everybody is an artist. That does not mean that everybody has to become a painter. Creativity means that a person has general abilities (64), creativity means having a part of the divine in oneself (110, 40, 42). Christ in this respect represents humanity. Beuys considers suffering, death, and resurrection as the basis for everyone’s life. Beuys in his interview with Mennekes summarises it thus:

This time Resurrection must instead be experienced by each person himself. One somehow must come to terms with one’s God. …. One somehow must come to terms with his God One must meet certain conditions, make certain efforts in order to come into contact with himself. And that is the true scientific sense of the word ‘creativity’. … It is only when a person creates this relationship that he can speak of his creative power … And this being has become free through his own development, primarily through the incarnation of the being of Christ amidst physical conditions of the earth (40, 42).

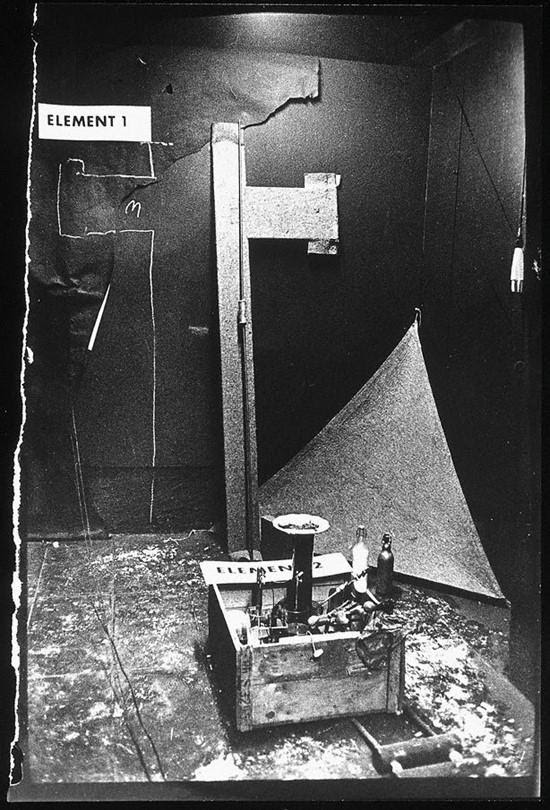

Beuys elaborated on this process of renewal in the Fluxus-demonstration Manresa on December 15, 1966 in a gallery in Düsseldorf. The question of the conditions for renewal of a human being and for the transformation of society was central. The Spanish place Manresa reminds us of the conversion of Ignatius of Loyola, with whom Beuys felt connected.

The Aktion consists of three elements. Element 1 is a half cross that is standing against the wall wrapped in felt; the other half is drawn with chalk on the wall. A copper staff is leaning against it. The two halves point to two worlds that have been separated, the one of mythical thinking directed towards synthesis and the one of analytical thinking in contrasts (or the one of intuition and the one of rational thinking. Element 2 is a wooden chest with electrical appliances, a plate with a cross and other objects standing opposite element 1. The same ‘substance,’ the same power reigns in both elements, although scattered and smashed in element 2. Beuys performs several actions between the two half crosses and the objects on the chest. On a sound recording you hear the question: ‘Where is element 3?’ With such a performance, too briefly sketched here, Beuys wants to raise awareness in the public mind about how the earthly and spiritual have drifted apart and calls for a renewed awareness and a renewed world (125-159).

A Cosmological Christology

The apostle Paul connects Christ with the creation: ‘For by him all things were created …. All things were created by him and for him’ (Colossians 1:16). Beuys does that in his way, as Rudolph Steiner had already done on the basis of an evolution of the world. Steiner had posited the primacy of the spiritual-divine and the spiritual in the world, out of which the cosmos develops in a differentiated way. Thus writes Steiner:

Thus the physical planet Earth has developed from out of a spiritual world being; and everything that is linked materially with this earth planet has formed from what was once linked with it spiritually (198).

In his speculative reflection Beuys’ starting point is also a world evolution in which divergent powers are at work: the powers of nature, the planetary movements and cosmic dimensions (204, 28). These develop into a web of cohesions of power in the world, in which Christ plays a fundamental role. The word ‘power’ also applies to our view of Christ in the present time, his resurrection, the spiritual power of the human being, the power of Christ or the impulse of Christ (66-68). With this Beuys points to what endures. He calls the enduring element: ‘substance,’ a terminology borrowed from the anthroposophist physical substance teaching of Rudolf Hauschka (204). For Beuys substance is something alive that is continually moving. It is more than a physical power and also concerns a spiritual, moral-ethical and spiritual power. In the Christ-Event substance is renewed, says Beuys. Christ is not just an important historical figure, but in Him heaven and earth touch each other. In this context he refers to Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan where the Spirit of God came down as a dove (Matthew 3:16).

If the Baptism in the Jordan had not taken place, a great historical personality would have certainly remained, like Mohammed …. but he would not have been the Christ, the spiritual substance, the sacrament, the concrete that transforms the whole world right into its material basis (46).

Every person can become a shape of a living substance, as Beuys says: ‘The Christ Impulse is … a cosmic event, which has in fact altered the whole substance in such a way that human beings, taking this as their starting point, can set on the path to freedom’ (206).

Even though I cannot always grasp Beuys’ cosmological thoughts, that does not detract from the fact that he with his Christ impulse in his own way has developed a theology of the Holy Spirit in the spirit of Steiner, which reminds us of John’s Gospel according to which Christ makes place for the Spirit (John 16:7,8; 20:22) and of Paul’s words: ‘I no longer live, but Christ lives in me’ (Galatians 2:20). With the help of his speeches, interviews, performances, display cases and environments Beuys designs a future order of society as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a transformation of humanity and the world, an evocation of a realm of peace and justice. Beuys’ art is not beautiful, but it makes a deep impression on me because his art presents humanity, society, and the natural world in their cohesion based on his spiritual view of life.

*******

Literature

G. Adriani, W. Konnertz, K. Thomas, Joseph Beuys: Leben und Werk. Köln: Dumont Buchverlag, 1986.

L. Beckmann, ‘The causes lie in the future’, 91-112, in: G. Ray (ed.), Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy. New York: D.A.P/Distributed Art Publishers, 2001, 91-111.

Joseph Beuys, Catalogue of the Centre Georges Pompidou. Paris, 1994.

J. Beuys, ‚Reden über das eigene Land: Deutschland‘, in: Joseph Beuys. Zu seinem Tode Nachrufe, Aufsätze, Reden. Bonn: Inter Nationes, 1986, 37-58.

J. Beuys, ‚Dank an Wilhelm Lehmbruck‘, in: Joseph Beuys. Zu seinem Tode Nachrufe, Aufsätze, Reden. Bonn: Inter Nationes, 1986, 61-65.

P. Kort, ‘Beuys. The Profile of a Successor’, in: G. Ray (ed.), Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy. New York: D.A.P/Distributed Art Publishers, 2001, 19-36.

F. Mennekes, Joseph Beuys: Christus Denken/Thinking Christ. Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk 1996.

P. Nisbet, ‘Crash Course: Remarks on a Beuys Story’, in: G. Ray (ed.), Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy. New York: D.A.P/Distributed Art Publishers, 2001, 5-17.

G. Ray, ‘Joseph Beuys and the after Auschwitz sublime’, in: G. Ray (ed.), Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy. New York: D.A.P/Distributed Art Publishers, 2001, 55-74.

M. Rosenthal ed., Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Houston/Tate Modern/London: Menil Collection, 2004.

H. Stachelhaus, Joseph Beuys, Berlin: Ullstein Buchverlage, 2013.

C. Tisdall, Joseph Beuys. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979.

A.van Zon, ‘Vrijheid door eenzaamheid en zelfverlossing: het kruis bij Joseph Beuys’, in: W. Stoker en O. Reitsma (red.), Kunst en religie. ’s-Hertogenbosch: Mathesis Pers, 2011, 105-121.

[1] J. Beuys, Reden über das eigene Land, 38.

[2] P. Kort, Beuys, 22.

[3] Kort, op. cit. 36.

[4] See fort his and the following quotes: J. Beuys, Danke an Wilhelm Lehmbruck, 62 en 63.

[5] J. Beuys, Reden über das eigene Land, 42; Beuys in an interview with F. Mennekes, Joseph Beuys: Christus Denken/Thinking Christ, 74,76.

[6] See for his founding of the ‘Organisation für direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (1971, 1 Juni): Adriani, Konnertz, Thomas, Joseph Beuys, 260-269.

[7] See for instance Beuys’ works SäFG–SäUG (1953/8) and Honigpumpe (1977) (Adriani, Konnertz, Thomas, Joseph Beuys, 46-53; 339-343).

[8] H. Stachelhaus, Joseph Beuys, 135; C. Tisdall, ‘Permanent conference’, in: Joseph Beuys, 265-282.

[9] See G. Jappe, ‘Interview with Beuys about key experiences September 27, 1976’ in: G. Ray (ed.), Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy, 185-198. About the role of his experience with the Tartars in his art, see P. Nisbet, Crash Course, 5-17.

[10] Joseph Beuys, Catalogue of Centre Georges Pompidou, 151.

[11] Stachelhaus, Joseph Beuys, 28-29.

[12] See G. Ray, Joseph Beuys and the after Auschwitz sublime, 59-67.

[13] In passing: Anselm Kiefer, a pupil of Beuys, repeatedly used the theme of hair, inspired by Paul Celans’ Todesfuge, in connection with the Holocaust in his art as in Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith (1981), Dein goldenes Haar, Margarete (1981), two leaden books entitled Sulamith (1990).

[14] Ray, a.w., 69.

[15] F. Mennekes, Joseph Beuys: Christus Denken/Thinking Christ.

[16] See for the cross as a constant theme with Beuys: A. van Zon, Vrijheid door eenzaamheid en zelfverlossing, 105-121.

[17] Beuys, Reden über das eigene Land, 38.