Historical Models for Crosses and Crucifixes Today

One Symbol – Plural Forms. Historical Models when Making Cross and Crucifix Forms Today

by Grete Refsum

Brief Abstract

Familiarity with historical material culture is in certain cases vital for innovation in art and

design production. In this paper, the cross or crucifix symbol exemplifies the statement.

All crosses and crucifixes symbolise joy and salvation. But formally there are two different

types: the victorious crucifix that depicts Christ alive standing on the cross, and the suffering

crucifix that shows the tortured, dead man hanging on the cross.

The crucifix that is regarded traditional in our time stems from the 16th century and is of the

suffering type that presupposes onlookers who know the Gospel story. Visually it

communicates the opposite of its intended happy meaning. Today, when the Christian

narrative is no longer commonly shared and understood, theologians and contemporary cross

or crucifix makers are challenged.

The paper accounts for the present historical understanding of Roman crucifixion; gives a

brief review of the development of the cross and crucifix as symbols of Christian faith;

presents basic varieties within cross and crucifix iconography; and exemplifies by a work of

the author, how knowledge about the historical material heritage can induce innovation.

Introduction

Familiarity with historical material culture is in certain cases vital for innovation in art and

design production. In this paper, the cross or crucifix symbol exemplifies the statement.

When dealing with ecclesial art or design tasks, reference to the Christian material heritage is

expected. Any period may be formally just as relevant as another. Still, the Roman Catholic

Church normatively asks for genuine Christian art from our own times, which means

contemporary interpretations of the Christian message that have significance for people today

(Refsum 2000), and Pope John Paul II frequently encourages artists and designers to work for

the Church (John Paul II 1999). The outcome of ecclesial art and design production in our

time, however, often falls into one of two categories: being either too traditional or too

inventive, neither of which represent the ecclesial wish. By knowing the ecclesial tradition

better, these pitfalls could be avoided.

Crosses and crucifixes in Christian contexts refer to the historical event that the Jew Jesus

from Galilee was crucified around the year 30 AD. Both symbolise the same meaning of

Christ’s redeeming offer of being killed and his triumphant resurrection from death that

became regarded as the salvation for humankind. Formally, crucifixes fall into two principal

categories: the victorious type that depicts Christ alive, and the suffering type that shows the

dead man hanging on the cross. The crucifix that we regard as the prototype today, with an

athletic man hanging dead on a Latin cross, is an interpretation of the suffering type that stems

from the 16th century. This crucifix type visually communicates the opposite of its intended

happy meaning; it presupposes that the Gospel story is known. Today, this may not be the

case. Here lies a challenge for contemporary cross or crucifix makers.

First, the paper accounts for the present historical understanding of Roman crucifixion.

Second, it gives a brief review of the development of the cross and the crucifix as symbols of

Christian faith. Third, it presents basic varieties within cross and crucifix iconography. And

forth, the author’s personal work exemplifies how historical models can induce innovation.

Historical realities concerning crucifixion

Crucifixion was used as a death penalty for enemies of the Roman state; its practice is

documented by contemporary Roman historians. Variations of methods were the rule;

probably the T-form was the most commonly used cross type (EB mic. vol. III: 266). The

crucifixion of Jesus is accounted for in the gospels only. These narratives offer little

information about formal aspects like cross form, crucifixion details and bodily posture.

Besides, the gospel stories are catechetical in ambition. According to the Irish American

biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan the detailed passion accounts are “not history

remembered, but prophesy historicized” (Crossan 1994: 145).

Although thousands of victims have been crucified, archaeological material of crucifixion is

almost non-existing because part of the crucifixion punishment was to obliterate the victim.

The corpses either were left on the crosses to be consumed by birds, or thrown into open

ditches to be prayed upon by animals (Crossan 1994: 127; Zias 1998: last page). The first and

only known remains of a crucified person were found in 1968, in a funeral chest in Jerusalem

at Giv’at ha-Mivtar. From this material evidence several positions of the crucified have been

reconstructed (Kuhn 1979: 315). Combining the favoured suggestion of crucifixion with the

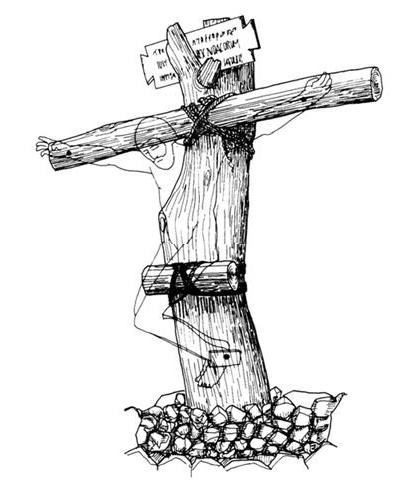

cross in the historical park of Jerusalem, a crucifixion scene can be reconstructed, figure 1.

Figure 1 Reconstruction of crucifixion (drawing: Jørgen Jensenius 2000) (Refsum 2000: 218).

Crucifixion was a method of torture intended to torment the victim slowly, it could be days. In

order to hasten death, the calf bones might be broken so that the victim fell down unable to

move upwards and breathe. It is supposed that Jesus died quickly because of his haemorrhage

caused by extensive whipping. The death cause may have been a combination of shock and

suffocation (Edwards et al. 1986: 1461).

Development of the Cross as Symbol of Christian Faith

The cross is found in both pre-Christian and non-Christian cultures where it has largely a

cosmic or natural signification. Two crossed lines of equal length signify the four directions of

the universe, and the swastika cross symbolizes the whirling sun, the source of light and power

(NCE vol. 4: 378). In the Old Testament, the Hebrew letter tau shaped like a T or an X, is used

as a sign that saves; the citizens of Jerusalem who marked their foreheads with this sign,

Yahweh would not exterminate (Ezekiel 9.4-6; JB, OT: 1369).

The significance of Christ’s death on the cross, according to Christian understanding, can be

learned from many references throughout the New Testament. All of them can be reduced to

one single idea: God’s great love for men. For Jews a man hanging on a tree was cursed.

When Jesus chose to be crucified, this act was understood as an offer that would redeem man

from the malediction of the Jewish Law, which posed obligations on people, but was unable to

save them from Yahweh’s punishment and hell. The crucifixion is seen as a mystical event

representing the redemptive work of Christ, and the fulfilment of the Old Testament. Through

Jesus the cross became a means of reconciling the sinful mankind and God. The cross,

therefore, represent the instrument of man’s liberation; it is the symbol of the redeemed

mankind (NCE vol. 4: 378).

The earliest Christians hardly used the cross, or worse the crucifix, to symbolize their faith.

The reasons may be many. First, the historical realities concerning crucifixion are gruesome.

Second, they were Jews accustomed to the prohibition of images in the Old Testament. Third,

the faith in a crucified male being God, was intellectually difficult to defend. Fourth,

Christianity was not legally accepted within the Roman Empire and Christians had to be

careful not to expose their belief. In consequence, few traces are left of a particular Christian

material culture before the 3rd century. However, Christianity was established in opposition to

contemporary religions that worshipped material things, the Roman emperor included.

The early Christians regarded their God as spiritual and superior to other deities, and they

had little need of religious objects and art (Finney 1994).

According to the late German scholar Erich Dinkler, the first known evidence of using the

cross – in this context T (tau) – to refer to Jesus, is from a fragment of a manuscript dated to

the second half of the 2nd century (Dinkler 1992: 341 and 345). Although the Jews had used

the tau as a sign of protection, this practice has no ideological connection to the later Christian

use of the cross. When the Christians adopted the cross as a symbol of their faith, it was an

invention based on different ideas (Dinkler 1967: 23-25). In the early 4th century, Constantine

the Great (280- 337) took Christianity as his religion, and abolished the execution method of

crucifixion. He marked his helmet and banner with the Greek letter X (Ch), which is the first

letter in Christ written in Greek. The subsequent development of the symbol of the cross seems

to stem from this Greek letter X, not a torture instrument (Thomas 1971). The Greek letters XP

became the Christ monogram, symbolizing that Christ had conquered death through resurrection.

Often the monogram was set in a circle of laurel, the contemporary symbol of victory. Such

iconography is seen on 4th century sarcophaguses, along with the Latin cross form, with

elongated vertical and shorter cross arms, the totality signifying everlasting life. In 326 AD,

mother of Constantine, Empress Helena, is said to have found the true cross on Golgotha.

This finding was at the time, regarded as empirical proof of resurrection. Its relics were

venerated and a new cross erected on the spot (Borgehammar 1991; Drijvers, 1992).

From then on, the interest in the cross started to grow.

According to Dinkler, the story of the cross as a symbol of Christianity seems to begin after

350 AD in the times of Emperor Theodosius the Great (379-395) and in Byzantium (Dinkler

1967: 74). And only long after, when most memories of Roman torture were forgotten, did the

crucifix become a symbol of Christian faith. The earliest known representation of Christ

crucified is a blasphemous graffiti from the 2nd century showing Christ as a donkey

(NCE vol. 4: 81). Proper crucifixes – a cross on which there is an image of Christ crucified

– appear next in the 5th century, integrated in the narrative of the life of Christ.

From the 6th century and three centuries on, the crucifix gradually separated from its narrative

context and became a symbol in itself, and in the 10th century, its basic iconographic forms

were established.

Cross and Crucifix Iconography

First comes the XP monogram, then the naked cross with variations and embellishments.

Then a symbol is included in the middle of the cross arms: the lamb, the bust of Christ,

and finally the complete figure of Christ, living with eyes open. On the first examples Christ

wears a loincloth, later he appears clothed in a sleeveless Roman tunic of honour. In the 8-9th

centuries, his eyes start to close, signalling death, and in the 10th century, the robe is replaced

by a loincloth. From then on, the representations of Christ on the cross oscillate between the

victorious type depicting Christ alive, standing on the cross with eyes open, and the suffering

type showing him hanging on the cross, tortured, dying or dead. During late medieval times the

latter type became European standard, increasingly more blood-dripping until crucifix iconography

culminated in the 16th century, in the moderated expression that still is regarded the prototype of

a crucifix: a handsome, athletic man nicely draped with a loincloth, hanging more or less dead on

a Latin cross (Lexicon der christlichen Iconographie 1970; Schiller 1968).1

The naked cross, the victorious and the suffering crucifix symbolise the same Christian

message, but with different theological accents (figures 2-4).

.jpg)

Figure 2 Early Irish cross, Kilmalkedar, county Kerry

Figure 3 Cross from Gloppen, height 2,13 m, 10-11th century (Birkeli 1973: 201),

(photo: Nordfjordeid museum)

Figure 4 Crucifix from Leikanger, figure 75,5 cm, 12th century (Blindheim 1980: 45),

(photo: Bergen museum)

The naked cross shows that Christ is risen; the victorious crucifix communicates the same,

stressing that Christ is God; while the suffering crucifix highlights the redeeming offer given

by the Son of God who was truly human (Hellemo 1996).

A Contemporary Crucifix Interpretation

Cross and crucifix makers have through the centuries added to the given iconography and

themselves become part of the tradition. Since the late 19th and throughout the 20th century,

countless artists have given their share to new interpretations (Landsberg 2001; Mennekes and

Røhrig 1994; Rombold and Schwebel 1983). Modernist crucifix interpretations basically

imply formal variations, changing materials and style, and most of them focus on the suffering

aspect. The artists often seem to identify their personal misery, the social situation or world affairs

with the crucifixion horror. Thus, the crucifix has become a metaphor of depicting injustice and evil.

Such interpretations may be artistically interesting, but from the ecclesial perspective, they may not

be satisfying in transmitting the joyful meaning of the crucifix. In consequence, the neo-classicist

varieties, often kitschy, have kept their position as ecclesial models. Regardless of 500 years of

theological thinking, Christianity today is branded with a kitschy version of a late medieval symbol

– no strange its adherents are declining! Resuming ecclesial practice and raising my children within

the Church, I felt the need to provide an alternative crucifix solution for catechetical reasons.

To vitalize or even redesign a traditional object, calls for actions beyond changing formal

aspects. One has to explore the origins of the object, why it came into use and what functions

it was to serve. By understanding the roots of the cross and the crucifix, its symbolic meaning,

significance, use and iconography, as outlined in this article, I came to see that these symbols

are not holy in themselves as objects; they are contemporary expressions intended to point

towards the Christian mystery as understood in it’s own times. Federico Borromeo’s teaching

on ecclesial art from the 17th century, was particularly influential on my thinking. He wished

artists to consider present understanding of sacred history and archaeological information in

order to demonstrate a rational attitude and guarantee historical authenticity, which he thought

would assert the authority of faith (Refsum 2000: 66-67; Jones 1993: 210). According to the

new, official and conservative Catholic Catechism, tradition written with a small letter t,

relates to that which is customary and manmade, through which the great Tradition, or faith,

is expressed. The particular forms of tradition, adapted to different places and times, can be

retained, modified or even abandoned (CCC A. 83; 25). Combining the gathered information

with the teachings of the Second Vatican Council’s on art from 1963, Sacrosanctum

concilium, chapter VII, (Vatican II 1981: 34-36), I felt free to experiment with form in my art

process as long as I was respectful towards faith and the Church.

The logic in my working process on the cross and crucifix that after nearly ten years, ended in

Divided Crucifix went as follows. Since little is known for certain concerning Christ’s

crucifixion, I abandoned realism and figuration. The Norwegian medieval triumphant

crucifixes nurtured my interest in the victorious aspect. The Irish Christian material heritage

and the cross from Gloppen inspired abstractions and geometric solutions (Refsum 2003). I

decided to abstract the crucifix figure, or the Godly aspect of Christ, into a ball. These threads

mingled together in Risen Cross that I regard as an abstract victorious crucifix, figure 5.

Figure 5 Figure Risen Cross 1991, height 165 cm

But Risen Cross lacks the suffering aspect. I realised that to contemplate grief and to proclaim

the glad tidings, existential darkness is needed as a contrast. But how can the joyful and the

sorrowful aspect be communicated equally in one symbol? My conclusion became that this is

impossible to express in one object.

Starting in the symbolic meaning, taking theology as point of departure, I got the idea to split

the cross or crucifix into separate parts, and let each part represent one aspect of the gospel

story. With four cross arms and one middle part that represent the Christ figure, I got five

pieces. In Divided Crucifix each part represents one liturgical event in which Christ plays a

specific role:

Palm Sunday – Christ is king

Maundy Thursday – the Eucharist is instituted

Gethsemane Garden – Christ suffers mentally

Good Friday – Christ suffers physically

Easter Morning – Christ is risen

The cross parts themselves are formed as abstractions of a male, height 180 cm. The gospel

narrative is visually communicated by the gradual twisting of the main form, and the changes

of the ball in the middle of the form, being present, moved, absent and returned, figure 6 and

7.

.jpg)

Figure 6 Drawn overview of Divided Crucifix

Figure 7 Divided Crucifix, St. Nikolai Church, Norway

Divided Crucifix tells a story of transformation from strength and gifts, through extreme pain,

mental and physical. It formally associates female experience and psychological thinking, to

being born and giving birth. Divided Cross is a catechetical work, intended to be used

liturgically, puzzled together from Lent to Easter Morning when it will be completed.

My aim was to provide a crucifix that visualized the complete Gospel story and ended in a

convincing resurrection. Divided Crucifix is not a variety of the Stations of the Cross, since

the Stations deal with Good Friday only. It is a suffering and a victorious crucifix combined.

Without studying the historical material culture, I hardly would have had the courage to

deconstruct the crucifix and suggest an innovation, and I would certainly not have had the

arguments to defend the result.

Abbreviations

A = article

CCC = Catechism of the Catholic Church

EB = The New Encyclopædia Britannica

JB = Jerusalem Bible

NCE = The New Catholic Encyclopedia

OT = Old Testament

Notes

1 One of the reasons for this iconographic standard is the Council of Trent (1545-1563) that lay down regulations on art. The Archbishop of Milan, Carlo Borromeo (1538-84), was the only writer who tried to work out the implications of them. In his Instruction, chapter VII, Sacred Images and Pictures, published in Milan 1577, is said: “First of all, no sacred image that contains any false teaching should be painted […] nor any that suggests an occasion of dangerous error to the uneducated; nor, again, any that is contradictory to Sacred Scripture and church tradition. Only such as conform to scriptural truth, traditions, ecclesiastical histories, custom and usage of our mother Church may be painted” (Voelker 1977: 228). Carlo Borromeo specifies further: “nothing false ought to be introduced […] anything that is uncertain, apocryphal, and superstitious; […] only that which is in agreement with custom” (Voelker 1977: 229). He continues: “whatever is profane, base or obscene, dishonest or provocative, whatever is merely curious and does not incite to piety, or that which can offend the minds and eyes of the faithful should be avoided” (Voelker 1977: 229).

In the early 17th century Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564-1631) founded the religious centre Ambrosiana with the purpose of reforming ecclesial scholarship and the figurative arts. In his book on sacred images, De Pictura Sacra, from 1624, Federico emphasized clarity and scriptural and iconographical accuracy in religious art. He recognized three interdependent roles of sacred art: the devotional, the didactic, and the documentary. Above all, ecclesial art should express the entire breadth of metaphysical reality, and appeal to all aspects of man: senses, emotions, intellect, and heart. Federico Borromeo wanted ecclesial art to make use of the research method and findings of sacred history in order to give images added potency. This indicated an adoption of certain approved portrait likenesses, iconographic details, and archaeological information, which should guarantee authenticity. He wished historical scenes to be recorded in an accurate manner in order to demonstrate a rational attitude, which he thought would assert the authority of faith see Jones 1993; Refsum 2000: 67).

Literature

Birkeli, Fridtjov. 1973. Norske steinkors i tidlig middelalder. Et bidrag til belysning av

overgangen fra norrøn religion til kristendom. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Borgehammar, Stephan. 1991. How the Holy Cross was Found. From Event to Medieval

Legend. Stockholm: Almquist &Wiksell International.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. 1995. London: Geoffrey Chapman.

Crossan, John Dominic. 1994. Jesus; A Revolutionary Biography. New York: Harper

SanFrancisco.

Dinkler, Erich. 1992. Im Zeichen des Kreuzes. Edited by E. Grässer. Vol. 61, Beihefte zur

Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche.

Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter.

———. 1967. Signum Crucis. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck).

Drijvers, Jan Willem. 1992. Helena Augusta. The Mother of Constantine the Great and the

Legend of Her Finding of the True cross. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Edwards, et al. 1986. On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ. JAMA March 21, Vol. 255 (No.

11):1455-1463.

Finney, Paul Corby. 1994. The Invisible God; The Earliest Christians on Art. New York,

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hellemo, Geir. 1996. Kristus lukker øynene. Noen synspunkt på tolkningen av middelalderske

krusifikstyper. In Studier i kilder til vikingtid og nordisk middelalder, edited by M.

Rindal. Oslo: Norges forskningsråd.

Jones, Pamela M. 1993. Federico Borromeo and the Ambrosiana. Art Patronage and Reform

in the Seventeenth-Century Milan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

John Paul II, Pope. To Artists. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/letters/1999/documents/hf_jp-ii_let_23041999_artists.html

Kuhn, Heinz-Wolfgang. 1979. Der Gekreutzigte von Giv'at ha-Mivtar. In Theologica Crucis-

Signum Crucis, edited by Carl Andresen and Günther Klein. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr

(Paul Siebeck).

Lexicon der christlichen Iconographie. Band II. 1970. Freiburg: Herder.

Mennekes, Friedhelm and Johannes Röhrig. 1994. Crucifixus: Das Kreuz in der Kunst unserer

Zeit. Freiburg: Herder.

Nordhagen, Per Jonas. 1981. Senmiddelalderens billedkunst 1350-1537. In Norges

kunsthistorie. Bind 2 Høymiddelalder og Hansa-tid, edited by K. Berg. Oslo:

Gyldendal norsk forlag.

Refsum, Grete. 2000. Genuine Christian Modern Art. Present Roman Catholic Directives on

Visual Art Seen from an Artist's Persepective. Dr. ing., Oslo School of Architecture,

Oslo.

Refsum, Grete. 2003. Historical Studies in Practice Based Art and Design Research. In

(theorising) History in Architecture, edited by E. Tostrup and C. Hermansen. Oslo:

Oslo School of Architecture.

Rombold, Günther and Schwebel, Horst. 1983. Christus in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts.

Freiburg, Basel, Wien: Herder.

Schiller, Gerturd. 1968. Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst. Die Passion Jesu Christi. Vol. 2.

Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus.

The Jerusalem Bible. 1966. Standard Edition. London: Darton, Longman & Todd.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia, Second Edition. 2003. Detroit: Thomson Gale in association

with The Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

The New Encyclopædia Britannica. 1978. London: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

Thomas, Charles. 1971. The Early Christian Archaeology of North Britain. Glasgow: Glasgow

University Publications.

Vatican II. The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents. 1981. Edited by A. Flannery, O. P.

Leominster, Herefords, England: Fowler Wright Book LTD.

Voelker, Evelyn Carole. 1977. Charles Borromeo's Instructiones Fabricae et Supellectilis

Ecclesiasticae, 1577. A Translation with Commentary and Analysis. UMI Dissertation

Services: Graduate School of Syracuse University.

Zias, Joe. 2004. Crucifixion in Antiquity. The Evidence [cited 21.10.2004]. Online

http://www.religiousstudies.uncc.edu/jdtabor/crucifixion.html.

Published 2005. In Pride & Predesign; the Cultural Heritage and the Science of Design.

Proceedings of Cumulus Spring Conference, edited by E. Côrte-R, C. A. M. Duarte

and F. C. Rodrigues. Lisboa: IADE, Instituto de Artes Visuais Design e Marketing.

Grete Refsum has a broad academic and artistic background; 1977, MA Environmental Manager, University of Agriculture; 1978, Examen Philosophicum, University of Oslo; 1985, Diploma, Painting/stained glass; 1992 MA, Form, National College of Art and Design; 2000, Dr. ing., Oslo School of Architecture. Refsum is currently part time (50 %) employed in Oslo National Academy of the Arts as Senior Adviser of research and development and as Adjunct Professor. Refsum has during 20 years contributed to the development of research in art and design through her artistic development work and practice-led research, publishing and taking part in the international discourse on these issues through many conferences and publications. Artistically, Refsum has systematically explored the Western Christian heritage and tradition, interpreting central themes like: the cross/crucifix, sacraments, prayer and liturgy. For the last 10 years, she has focused on prayer/meditation. Refsum is a pioneer of using art experimentally in catechesis and ecclesial spaces. Her practice comprises: embellishments, art interventions, performances, workshops and shows of various kinds. Several of her art works are regularly being used liturgically. www.refsum.no

More:

11 July 2024 / TEARS OF GOLDJonathan Evens interviews Hannah Rose Thomas

Read more...02 May 2024 / Interview with Gert Swart

28 March 2024 / Stations of the Cross in Hornsea

Matthew Askey's most recent project is a set of ‘Stations of the Cross’ for St Nicholas Church, Hornsea. This is a site-specific commission of paintings that link each Station to a part of the town.

Read more...28 February 2024 / Book review Abundantly More

01 February 2024 / James Tughan: CONTACT

13 October 2023 / David Miller Interview

“Form welcomes the formless home”

Jonathan Evens interviews David Miller on his work and the “interrelation, symbiosis and overlap” between writing and visual art

Read more...07 August 2023 / Ethnoarts Scripture Engagement

by Scott Rayl

Ethnoarts are artistic ‘languages’ that are unique to a particular community. They can help strengthen cultural and Christian identity.

Read more...12 June 2023 / Georges Rouault and André Girard

by Jonathan Evens

Rouault and Girard: Crucifixion and Resurrection, Penitence and Life Anew

Read more...28 April 2023 / Josh Tiessen: Vanitas + Viriditas

28 April - 26 May, New York gallery Rehs Contemporary will present Josh Tiessen: Vanitas and Viriditas.

Read more...10 April 2023 / Images for God the Father

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

How can we ever comprehend God the Father with our small human intellects? How can we ever get to know Him and learn to live with Him?

Read more...16 February 2023 / Ervin Bossanyi: A vision for unity and harmony

by Jonathan Evens

Bossanyi joined the large number of émigré artists arriving in Britain after WW II, many of whom were Jewish and explored spirituality within their work.

Read more...06 January 2023 / The Creative Process

by Colin Black

Creative journeys are full of mishaps, accidents, and wrong turnings.

Read more...01 December 2022 / ArtWay newsletter 2022

Artway will be continued by the Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology from the beginning of 2024.

Read more...20 October 2022 / Kuyper, the Aesthetic Sphere, and Art

After three centuries of silence about art in Reformed theological circles in the Netherlands, suddenly there was Abraham Kuyper, whose great merit it was that he once again drew attention to art.

Read more...06 September 2022 / On the Street: The work of JR

by Betty Spackman

Through the project in Tehachapi JR wanted to "give voice to prisoners" and humanize their environment.

Read more...04 August 2022 / Joseph Beuys: A Spiritual German Artist

Is there a thread that connects the multifaceted work of this artist? My hypothesis is that Beuys’ spirituality is what drives his diverse work.

Read more...01 June 2022 / Interview with Belinda Scarlett

BELINDA SCARLETT, theatre costume and set designer and ecclesiastical textile artist

Interview by JONATHAN EVENS

Read more...21 April 2022 / Betty Spackman: A Creature Chronicle

When I consider the heavens, the moon and the stars that you have made, what are mere mortals that you are mindful of them… Psalm 8

Read more...16 March 2022 / Three artworks by Walter Hayn

by Gert Swart

These three artworks must have turned Walter Hayn inside out, being so powerfully revealing.

Read more...22 February 2022 / Abstract Expressionism

by Nigel Halliday

It is worth the while to remember the deep seriousness of these artists – even if their suggested answers can look sadly thin.

Read more...07 January 2022 / Artist duo Gardner & Gardner

by Elizabeth Kwant

During COP26 artist duo Gardner & Gardner installed their work I will learn to sit with you and I will learn to listen in Glasgow Cathedral.

Read more...09 December 2021 / ArtWay Newsletter and List of Books 2021

Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker intends to phase out her participation in the day to day oversight of the ArtWay website over the course of the coming new year.

Read more...03 November 2021 / The Seven Works of Mercy in Art

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

This overview will show that these artworks from different ages mirror the theological ideas and the charitable works of their times.

Read more...06 October 2021 / Disciplining our eyes with holy images

by Victoria Emily Jones

Images tend to work a subtle magic on us, especially after years of constant exposure.

Read more...24 August 2021 / On the Gifts of Street Art

by Jason Goroncy

These works represent an act of reclaiming public space for citizens rather than merely consumers.

Read more...27 July 2021 / Russia’s 1st Biennale of Christ-centered Art

An opportunity of dialogue between the church and contemporary art

by Viktor Barashkov

Read more...30 June 2021 / Jacques and Raïssa Maritain among the Artists

by David Lyle Jeffrey

About the influence of Jacques and Raïssa Maritain on Rouault, Chagall and Arcabas.

Read more...13 May 2021 / GOD IS...

Chaiya Art Awards 2021 Exhibition: “God Is . . .”

by Victoria Emily Jones

Read more...21 April 2021 / Photographing Religious Practice

by Jonathan Evens

The increasing prevalence of photographic series and books exploring aspects of religious practice gives witness to the return of religion in the arts.

Read more...23 March 2021 / Constanza López Schlichting: Via Crucis

Perhaps what may be different from other Stations of the Cross is that it responds to a totally free expression and each station is a painting in itself.

Read more...10 February 2021 / Gert Swart: Four Cruciforms

In a post-Christian era, contemporary Christian artists have to find new ways of evoking the power of the cross.

Read more...08 January 2021 / Reflecting on a Gauguin Masterpiece

by Alan Wilson

An artist's reflection on Impressionism, Cezanne, Van Gogh and especially Gauguin's Vision after the Sermon.

Read more...11 December 2020 / ArtWay Newsletter 2020

What makes the ArtWay platform so special is its worldwide scope thanks to its multilingual character. There are ArtWay visitors in all countries on this planet.

Read more...27 October 2020 / Art Pilgrimage

A Research Project on Art Stations of the Cross

by Lieke Wijnia

Read more...18 September 2020 / Interview with Peter Koenig

by Jonathan Evens

Koenig's practice demonstrates that the way to avoid blandness in religious art is immersion in Scripture.

Read more...17 August 2020 / BOOK REVIEW BY HEINRICH BALZ

How Other Cultures See the Bible

Christian Weber, Wie andere Kulturen die Bibel sehen. Ein Praxisbuch mit 70 Kunstwerken aus 33 Ländern.

Read more...17 July 2020 / The Calling Window by Sophie Hacker

by Jonathan Evens

In 2018 British artist Sophie Hacker was approached to design a window for Romsey Abbey to celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of Florence Nightingale.

Read more...12 June 2020 / A little leaven leavens the whole lump

From South Africa

Ydi Carstens reports on the group show ‘Unleavened’ which was opened in Stellenbosch shortly before the Covid-19 lock-down.

Read more...14 May 2020 / Jazz, Blues, and Spirituals

Republished:

Hans Rookmaaker, Jazz, Blues, and Spirituals. The Origins and Spirituality of Black Music in the United States.

Reviewed by Jonathan Evens

Read more...17 April 2020 / Andy Warhol: Catholicism, Work, Faith And Legacy

by Jonathan Evens

While Warhol’s engagement with faith was complex it touched something which was fundamental, not superficial.

Read more...25 March 2020 / Sacred Geometry in Christian Art

by Sophie Hacker

This blog unravels aspects of sacred geometry and how it has inspired art and architecture for millennia.

Read more...22 February 2020 / Between East and West

By Kaori Homma

Being in this limbo between day and night makes me question, “Where does the east end and the west start?”

Read more...15 February 2020 / Imagination at Play

by Marianne Lettieri

To deny ourselves time to laugh, be with family and friends, and fuel our passions, we get caught in what Cameron calls the “treadmill of virtuous production.”

Read more...07 December 2019 / ArtWay Newsletter 2019

An update by our editor-in-chief

and

the ArtWay List of Books 2019

16 November 2019 / Scottish Miracles and Parables Exhibition

Alan Wilson: "Can there be a renewal of Christian tradition in Scottish art, where ambitious artists create from a heartfelt faith, committed to their Lord and saviour as well as their craft?"

Read more...23 September 2019 / Dal Schindell Tribute

While Dal’s ads and sense of humour became the stuff of legends, it was his influence on the arts at Regent College in Vancouver, Canada that may be his biggest legacy.

Read more...04 September 2019 / The Aesthetics of John Calvin

Calvin stated that 'the faithful see sparks of God's glory, as it were, glittering in every created thing. The world was no doubt made, that it might be the theater of divine glory.'

Read more...31 July 2019 / The Legend of the Artist

by Beat Rink

The image of the 'divine' artist becomes so dominant that artists take their orientation from it and lead their lives accordingly.

Read more...02 July 2019 / Quotes by Tim Keller

Many “Christian art” productions are in reality just ways of pulling artists out of the world and into the Christian subculture.

Read more...08 June 2019 / The Chaiya Art Awards

by Jonathan Evens

The Chaiya Art Awards 2018 proved hugely popular, with over 450 entries and more than 2,700 exhibition visitors.

Read more...29 May 2019 / Art Stations of the Cross: Reflections

by Lieke Wynia

In its engagement with both Biblical and contemporary forms of suffering, the exhibition addressed complex topical issues without losing a sense of hope out of sight.

Read more...03 May 2019 / Marianne Lettieri: Relics Reborn

Items that show the patina of time and reveal the wear and tear of human interaction are carriers of personal and collective history.

Read more...27 April 2019 / Franciscan and Dominican Arts of Devotion

by John Skillen

This manner of prayer stirs up devotion, the soul stirring the body, and the body stirring the soul.

Read more...13 March 2019 / Makoto Fujimura and the Culture Care Movement

by Victoria Emily Jones

Culture care is a generative approach to culture that brings bouquets of flowers into a culture bereft of beauty.

Read more...08 January 2019 / Building a Portfolio of People

by Marianne Lettieri

Besides hard work in the studio, networking may be the single most important skill for a sustainable art practice.

Read more...01 December 2018 / ArtWay Newsletter December 2018

ArtWay has Special Plans for 2019!

After London, Washington D.C. and New York the city of Amsterdam in the Netherlands is now the anticipated location for a prominent art exhibition with the title Art Stations of the Cross.

Read more...11 October 2018 / The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe

Book Review by Jonathan Evens

The significance and spirituality of the work is made clear in ways which counteract the stereotype of mass production of a static style.

Read more...13 September 2018 / A Visit to the Studio of Georges Rouault

by Jim Alimena

Everything we saw and learned reinforced my picture of a great man of faith and a great artist.

Read more...09 August 2018 / With Opened Eyes: Representational Art

by Ydi Coetsee

How do we respond to the ‘lost innocence’ of representational art?

Read more...13 July 2018 / True Spirituality in the Arts

by Edith Reitsema

Living in Christ should lead us away from living with a segregated view of life, having a sacred-secular split.

Read more...17 May 2018 / Beholding Christ in African American Art

Book review by Victoria Emily Jones

One of the hallmarks of Beholding Christ is the diversity of styles, media, and denominational affiliations represented.

Read more...23 April 2018 / Short Introduction to Hans Rookmaaker

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

On the occasion of the establishment of the Rookmaaker Jazz Scholarship at Covenant College, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 12 March 2018

Read more...04 April 2018 / International Art Residency in India

Art for Change, a New Delhi based arts organization with a vision to see art shape society with beauty and truth, will be running its 6th annual International Artist Residency in November 2018.

Read more...15 March 2018 / The Stations of the Cross at Blackburn Cathedral

by Penny Warden

Perhaps the central challenge for the artist in imaging the body of Christ is the problem of representing the dual natures of the doctrine of the incarnation.

Read more...23 February 2018 / Between the Shadow and the Light

By Rachel Hostetter Smith

In June 2013 a group of twenty North American and African artists from six African countries met for two weeks of intensive engagement with South Africa.

Read more...30 January 2018 / Sacred Geometry in Christian Art

by Sophie Hacker

This blog unravels aspects of sacred geometry and how it has inspired art and architecture for millennia.

Read more...01 January 2018 / Jonathan Evens writes about Central Saint Martins

Why would Central Saint Martins, a world-famous arts and design college and part of University of the Arts London, choose to show work by its graduates in a church?

Read more...06 December 2017 / ArtWay Newsletter December, 2017

ArtWay's Chairman Wim Eikelboom: "The visual arts cultivate a fresh and renewed view of deeply entrenched values. That is why ArtWay is happy to provide an online platform for art old and new."

Read more...14 November 2017 / The Moral Imagination: Art and Peacebuilding

In the context of conflict transformation the key purpose of creative expression is to provide a venue for people to tell their stories, and for their stories to be heard.

Read more...24 October 2017 / Bruce Herman: Ut pictura poesis?

For the last couple hundred of years the arts have largely been in "experimentation mode"—moving away from the humble business of craft and service toward ideas, issues, and theory.

Read more...04 October 2017 / David Jeffrey: Art and Understanding Scripture

The purpose of In the Beauty of Holiness: Art and the Bible in Western Culture is to help deepen the reader’s understanding of the magnificence of the Bible as a source for European art.

Read more...08 September 2017 / David Taylor: The Aesthetics of John Calvin

Calvin stated that 'the faithful see sparks of God's glory, as it were, glittering in every created thing. The world was no doubt made, that it might be the theater of divine glory.'

Read more...23 August 2017 / Reconstructed by Anikó Ouweneel

A much talked-about exposition in the NoordBrabants Museum in The Netherlands showed works by modern and contemporary Dutch artists inspired by traditional Catholic statues of Christ and the saints.

Read more...04 July 2017 / Pilgrimage to Venice – The Venice Biennale 2017

When I start to look at the art works, I notice a strange rift between this pleasant environment and the angst and political engagement present in the works of the artists.

Read more...24 June 2017 / Collecting as a Calling

After many years of compiling a collection of religious art, I have come to realize that collecting is a calling. I feel strongly that our collection has real value and that it is a valuable ministry.

Read more...02 June 2017 / I Believe in Contemporary Art

By Alastair Gordon

In recent years there has been a growing interest in questions of religion in contemporary art. Is it just a passing fad or signs of renewed faith in art?

Read more...04 April 2017 / Stations of the Cross - Washington, DC 2017

by Aaron Rosen

We realized that the Stations needed to speak to the acute anxiety facing so many minorities in today’s America and beyond.

Read more...07 March 2017 / Socially Engaged Art

A discussion starter by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Growing dissatisfaction with an out-of-touch, elite and market driven art world has led artists to turn to socially engaged art.

Read more...01 February 2017 / Theodore Prescott: Inside Sagrada Familia

The columns resemble the trunks of trees. Gaudi conceived of the whole interior as a forest, where the nave ceiling would invoke the image of an arboreal canopy.

Read more...03 January 2017 / Steve Scott tells about his trips to Bali

In the Balinese shadow play the puppet master pulls from a repertoire of traditional tales and retells them with an emphasis on contemporary moral and spiritual lessons.

Read more...09 December 2016 / Newsletter ArtWay December 2016

Like an imitation of a good thing past, these days of darkness surely will not last. Jesus was here and he is coming again, to lead us to the festival of friends.

Read more...01 November 2016 / LAbri for Beginners

What is the role of the Christian artist? Is it not to ‘re-transcendentalise’ the transcendent, to discern what is good in culture, and to subvert what is not with a prophetic voice?

Read more...30 September 2016 / Book Review by Jonathan Evens

Jonathan Koestlé-Cate, Art and the Church: A Fractious Embrace - Ecclesiastical Encounters with Contemporary Art, Routledge, 2016.

Read more...01 September 2016 / Review: Modern art and the life of a culture

The authors say they want to help the Christian community recognize the issues raised in modern art and to do so in ways that are charitable and irenic. But I did not find them so. Their representation of Rookmaaker seems uncharitable and at times even misleading.

Read more...29 July 2016 / Victoria Emily Jones on Disciplining our Eyes

There’s nothing inherently wrong with images—creating or consuming. In fact, we need them. But we also need to beware of the propensity they have to plant themselves firmly in our minds.

Read more...30 June 2016 / Aniko Ouweneel on What is Christian Art?

Pekka Hannula challenges the spectator to search for the source of the breath we breathe, the source of what makes life worth living, the source of our longing for the victory of redemptive harmony.

Read more...09 June 2016 / Theodore Prescott: The Sagrada Familia

Sagrada Familia is a visual encyclopedia of Christian narrative and Catholic doctrine as Gaudi sought to embody the faith through images, symbols, and expressive forms.

Read more...19 May 2016 / Edward Knippers: Do Clothes make the Man?

Since the body is the one common denominator for all of humankind, why do we fear to uncover it? Why is public nudity a shock or even a personal affront?

Read more...27 April 2016 / Alexandra Harper: Culture Care

Culture Care is an invitation to create space within the local church to invest our talents, time and tithes in works that lean into the Kingdom of God as creative agents of shalom.

Read more...06 April 2016 / Jonathan Evens on Contemporary Commissions

The issue of commissioning secular artists versus artists of faith represents false division and unnecessary debate. The reality is that both have resulted in successes and failures.

Read more...12 March 2016 / Betty Spackman: Creativity and Depression

When our whole being is wired to fly outside the box, life can become a very big challenge. To carve oneself into a square peg for the square holes of society, when you are a round peg, is painful to say the least.

Read more...24 February 2016 / Jim Watkins: Augustine and the Senses

Augustine is not saying that sensual pleasure is bad, but that it is a mixed good. As his Confessions so clearly show, Augustine is painfully aware of how easily he can take something good and turn it into something bad.

Read more...11 February 2016 / H.R. Rookmaaker: Does Art Need Justification?

Art is not a religion, nor an activity relegated to a chosen few, nor a mere worldly, superfluous affair. None of these views of art does justice to the creativity with which God has endowed man.

Read more...26 January 2016 / Ned Bustard: The Bible is Not Safe

Revealed is intended to provoke surprise, even shock. It shows that the Bible is a book about ordinary people, who are not only spiritual beings, but also greedy, needy, hateful, hopeful, selfish, and sexual.

Read more...14 January 2016 / Painting by Nanias Maira from Papua New Guinea

In 2011 Wycliffe missionary Peter Brook commissioned artist Nanias Maira, who belongs to the Kwoma people group of northwestern Papua New Guinea, to paint Bible stories in the traditional style for which he is locally known.

Read more...