Images for God the Father

Images for God the Father

by Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker

God is spirit. God is a mystery. He is awe-inspiringly exalted and at the same time unimaginably loving. How can we ever comprehend Him with our small human intellects? How can we ever get to know Him and learn to live with Him?

That would not be possible without the Bible, where God reveals himself to us in stories and images. In the Bible we first of all meet God as creator and founder of heaven and earth, as the breathtakingly creative artist who invented everything that exists and called it to life. We meet him as a king full of majesty, who guides everything and holds it all in his hand. We get to know him as a caring and loving Father. God as Father is also an image for God, given to us by Jesus. God as our Father is perhaps the essence of his being, indicative of a deep longing for connection with us as his children.

The Bible offers us many more images for God, too many to enumerate. The eye is used to symbolise God’s omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence. Fire is also often employed: destructive fire, purifying fire, an illuminating column of fire or a burning bush that is aflame but not consumed. God’s presence and guidance come to expression in the pillar of cloud which led the Israelites through the desert. God is our rock, our fortress, our shepherd, potter, shadow on our right hand. We also come across feminine images for God: for example God as a mother hen, who gathers her chickens under her wings.

As human beings we need these images to make God real for us. It is therefore not surprising that the Bible leads the way in giving us images for God and also gives us space to form our own, even though an image always conveys only one aspect of God. Just as God is inexpressible in words, he is also inexpressible in images. They are and always remain limited symbolic indications of God.

The Second Commandment

When we think about making images of God in the sense of statues, we are immediately reminded of the second commandment: ‘You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them (Deuteronomy 5:8-9). It is especially important that we do not separate the two parts of this commandment, because it is not about the making of statues or sculptures in general, but about the production of idols. God does not want us to worship him via carved images. Why not? I think because a statue of a higher power that you approach with sacrifices in order to plead for its favour, will soon lead to a relationship with that deity where you will do whatever it takes to make him favourable and if possible to bend him to your will. That is totally different from the ‘I am who I am’ who God wants to be for us, a God of whom we may know that He is there for us, that He will journey with us and wants to be near us.

In view of the second commandment and its sculpture-hostile explanation, we need not be surprised that Christians through the ages have exercised caution concerning depicting God. And yet artists have dealt with this more freely than you would expect. A sarcophagus from the 4th century shows God the Father as a seated man who calls Adam and Eve into life with a speech gesture. In the Middle Ages He was especially portrayed via symbols such as the eye of God or the hand of God making a gesture of blessing from out of a cloud or halo. Or as a sun representing divine light, a circle referring to his eternity, or a sceptre or throne representing his dominion.

In the 15th century artists began to render God as a wise old greybeard, an image derived from Daniel 7:9 and Revelation 1:14. We are all familiar with this way of depicting God from the Creation of Adam by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Raphael (1483-1520) goes a step further in his painting of Ezekiel’s vision of God (Ezekiel 1). As a Renaissance artist he wanted to combine the classical and Christian traditions. His rendering of God was therefore influenced by the representations of the Roman supreme god Jupiter. In the spirit of his era and with all the means available to him Raphael here conveys the glory of Ezekiel’s magnificent vision.

We see God sitting above the clouds on his throne, supported by two cherubins and the four creatures (man, ox, lion, and eagle) that were later associated with the four evangelists. His hands are shown in a gesture of blessing. The golden-yellow sky emphasises his divinity and contrasts with earthly reality. What is so special in this painting is that God occupies the larger part of the canvas, while Ezekiel is just a tiny figure in the left corner of the work. Through a small opening in the clouds he catches a glimpse of the immensely superior God. Next he lifts his hands in worship. A work such as this can help us take in God’s majesty.

John Calvin

“But, because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each, lest those things which the Lord has conferred on us for his glory and our good be not polluted by perverse misuse.” (ICR I. XI. 12). This quotation from the Institutes makes clear that Calvin was not against art per se, but especially against how it was used in the devotional practices of his time. In line with the second commandment Calvin maintained that it is wrong to worship statues or to pray to God via statues. In so doing you limit the presence of God to specific statues and places, he argued, while God is always with us and we can pray to him wherever we are. That is why Calvin not only wanted to remove statues from the church, but also to lock the doors of the churches during the week.

Furthermore Calvin was against depicting God and Jesus in general. He feared that representations of God and Jesus could not do justice to their majesty and would always fall short. Calvin thought that “nothing was more unseemly than to want to reduce God, who is immeasurable and incomprehensible, to 1 metre 50.” In his wake we see Calvinist artists who held strictly to Calvin’s ideas about art as well as a movement that operated more freely. The stricter group refrained from picturing God, Christ and angels and their work was mostly limited to the Old Testament. Rembrandt belonged to the more liberal group, while he was a master in employing light in his paintings to suggest the presence of God.

The Bible as a Book of Images

Images, metaphors and an evocative way of speaking play a very large role in the Bible. The Bible is a book of images. The Bible contains very little straightforward theological explanation. The greater part of Scripture consists of stories, poetry, songs, parables and even performances, like Isaiah who was going about stark naked for three years, and Jeremiah, who carried a yoke for a long time. Or Jesus, who washed the feet of his disciples.

Why does the Bible do so? Because in this way the message of the Bible does not remain abstract but is made concrete. The stories, parables, metaphors, visions and representational actions bring the message closer to home. They literally speak to our imagination. They invite us to enter into the image and to participate in the story. We feel the emotions and identify with the people who play a role in the story. We are being addressed at a deeper level than just our intellect. When you sing Psalm 23, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’, you wonder what that exactly means and you imagine how God cares for you as a sheep. How He is concerned for you and sets off to find you. How He looks at you when He at long last finds you. Images create a space for the imagination to dwell and roam around in, to explore and investigate and discover new things, about yourself, about reality, and about God.

The Dutch Catholic art historian Frits van der Meer said: “The Word is more exalted, but the image is closer by.” The word can catch abstract truths in words, can list things and explain them, it can construct ingenious theories, but an image makes concrete, enables us to visualize things and to experience the emotional weight and meaning – in one fell swoop, in one picture. A small difference in nuance, in posture or facial expression can tell a whole story. In order to convey that in words you would indeed need 1000 or more words. Furthermore: because an image makes ideas visible and concrete and allows us to experience the emotional value of objects, it more readily addresses our heart. An image is closer by, closer to our heart. In knowing God, not only our intellect plays a role, but also our emotions, imagination and own experience.

One’s Own Images for God

In 1922 the German expressionist sculptor, Ernst Barlach, made a unique sculpture of God the Father. God hovers above the earth, keeping his eyes closed and his look averted, as if He can’t bear to look at the swarms of human life. However, his arms are reaching down as far as possible, with hands that are calling, welcoming, and desiring to draw to himself all those obstinate people in order to care for them. That is the split God is sitting in. The sculpture is so unparalleled, because here Barlach attempts to get under God’s skin and wonders how He must be feeling about a humanity that is making such a mess of life.

With the Bible and works of art as guides, we can ponder about who God is for us, because ultimately that is a personal matter. The way I experience God can be different from the way you experience God. Conversely, God deals with each one of us in a unique way that is individually attuned to us. For myself it is important that God is a rock, giving me a secure footing, that He as a Shepherd gives me both freedom and guidance and as a Father loves and cares for me. Everyone can and may make an image for God that speaks most appropriately to his life and imagination. What is your image for God?

***

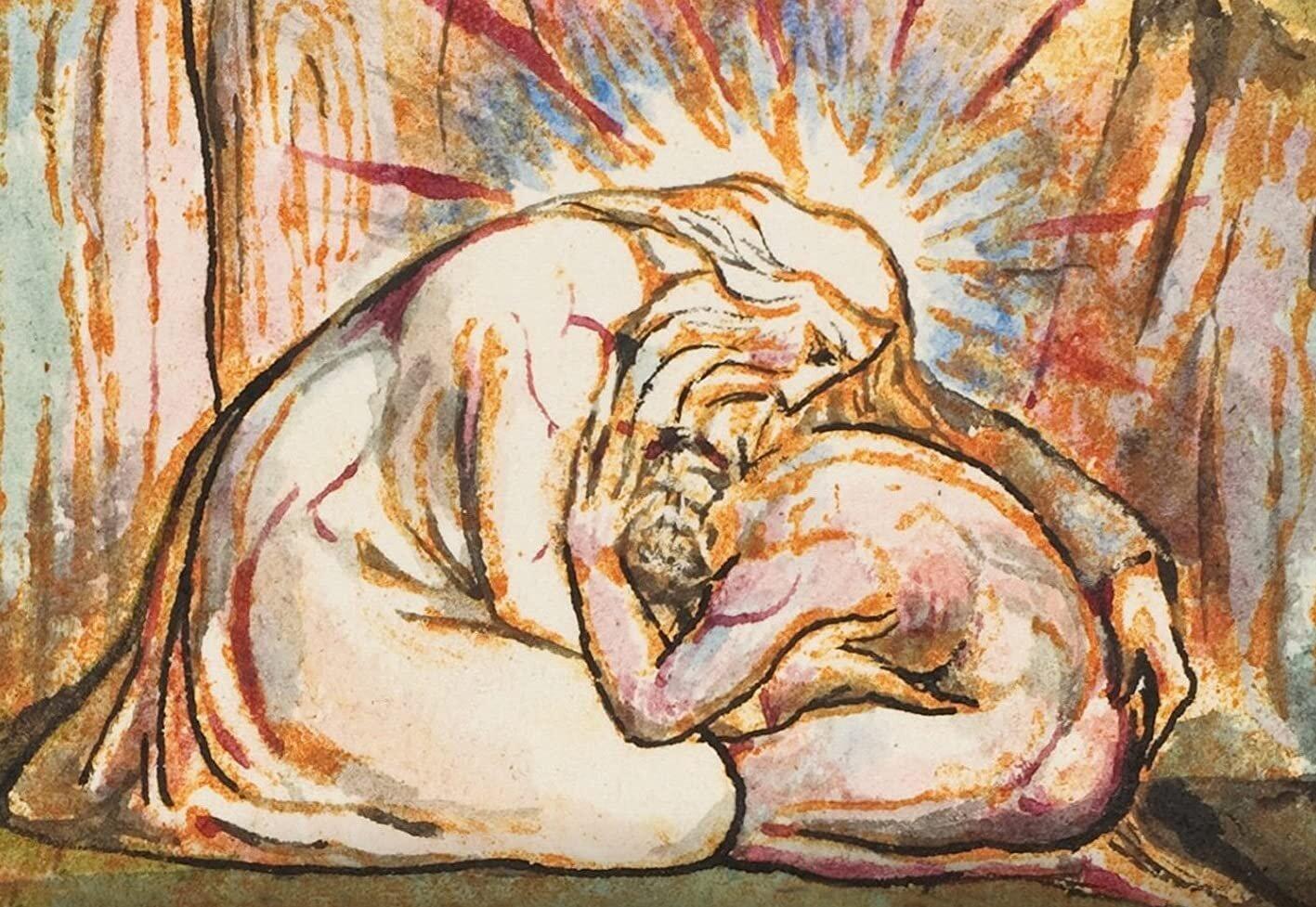

William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience: The Little Vagabond, 1825. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Raphael: Ezekiel’s Vision, c.1518. Uffizi, Florence.

Rudolf Marschall: The Good Shepherd, c. 1920. Vatican Museum, Rome.

Ernst Barlach: Schwebender Gottvater, 1922. Barlachhaus, Hamburg.