England: St Michael and All Angels Berwick

St Michael and All Angels Berwick

by Jonathan Evens

‘Whether it be music or painting or drama, sculpture or architecture or any other form of art, there is an instinctive sympathy between all of these and the worship of God. Nor should the church be afraid to thank the artists for their help, or to offer its blessing to the works so pure and lovely in which they seek to express the Eternal Spirit. Therefore I earnestly hope that in this diocese (and in others) we may seek ways and means for a reconciliation of the Artist and the Church—learning from him as well as giving to him and considering with his help our conception alike of the character of Christian worship and of the forms in which the Christian teaching may be proclaimed.’

On 27th June 1929, the day he became Bishop of Chichester, George Bell famously expressed, in his enthronement address, his commitment to a much closer relationship between the Anglican Church and the arts.

Rowan Williams has argued that Bell's acceptance of Christian witness is shaped by a twofold responsibility: ‘Responsibility to the culture in which the Christian community is located and responsibility for it. On the one hand, Christians are 'answerable' to the ambient culture in the sense that they are there not to dictate but to serve; the Church is not a body that arbitrarily sets the agenda for society at large, but seeks to discern what needs it must meet. It therefore has to develop a degree of attention to the culture in which it lives, if only so that it doesn't find itself (as has often been said) answering questions that no-one is asking. On the other hand, with the Jewish prophetic tradition much in mind and the New Testament imagery of the believing community as salt, leaven and light, Christians are answerable to God for the integrity and justice of their society; they may not be setting an agenda but they are discerning what is destructive and warning against it – and the refusal to utter such a warning leaves the believer exposed to judgement. The balance is a difficult one, and very few individuals or particular churches get it right for long. Answerability to the culture can produce a lack of confidence within the Church in its own distinctive gifts, and at worst an uncritical reproduction of the culture's attitudes with a faint pious gloss. Answerability for the culture can generate obsessional confrontation, something like paranoia about cultural and moral decline and a weddedness to the luxuries of a permanent minority position which allows criticism without practical engagement.’ (http://rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org/articles.php/1348/university-of-chichester-bishop-george-bell-lecture#sthash.SEZNoRG0.dpuf)

What is impressive about Bell, Williams suggests, ‘is not only his ability to hold the tension, with an apparent lack of self-consciousness that is remarkable, but also the way in which the two concerns appear in his biography as intricately interwoven.’

Bell had been intent on re-establishing the link between the Church and the arts from his early days as dean of Canterbury (1924-9) where he had begun with religious drama, commissioning in 1928 a new play for the cathedral from John Masefield; an event which in large part led to the establishing of a series of Canterbury plays, including Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot. He went on to commission drama, music and visual art, put structures in place (e.g. the Sussex Churches Art Council and its ‘Pictures in Churches Loan Scheme’) to support a wider commissioning of artists, placed his trust in the vision of artists when they encountered opposition and he was called on to adjudicate on commissions and strongly supported the appointment of Walter Hussey as Dean of Chichester Cathedral to take forward the commissioning programme he had initiated there.

Bell viewed his drive to re-associate the Church and the Arts as being “an effective protection against barbarism, whether the barbarism was Nazism, materialism or any other threat to civilization.” Murals commissioned from Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Quentin Bell in 1941 for the Sussex Church of St Michael & All Angels Berwick represented a fulfilment of his vision to be a catalyst for promoting the relationship between the Arts and the Church. As Sir Kenneth Clarke wrote in 1941: “...with a little judicious publicity it might have the effect of encouraging other dioceses to do the same. If once such a movement got under way, it would have incalculable influence for the good on English Art.”

The commission for the murals came about in the following way: ‘Sir Kenneth Clark announced in a letter to the Times (1939) the formation of the Central Institute of Art and Design (CIAD) whose purpose was to respond to the plight of artists in wartime … It was a cause that Bell passionately identified with and almost immediately he took up the challenge of stimulating Church patronage of the Arts within his own diocese. He received enthusiastic support from Sir Kenneth Clark at the CIAD and within his diocese from Professor Charles Reilly who had a home near Brighton. The CIAD introduced Bell to the Society of Mural Painters whose membership included both Hans Feibusch, who offered to undertake commissions in the Diocese for no fee, and Duncan Grant who was also a committee member of the CIAD.

Feibusch was the first to complete murals in the Diocese and Prof. Reilly heralded his work at St Wilfrid's, Brighton in 1940 as the first ‘modern’ murals in any English church. By ‘modern’ he meant: a painting belonging to the present generation and based in its forms and colour on the revolution in the graphic arts brought about by the researches and experiments of Cezanne and Picasso.

Prof. Reilly was credited by Bishop Bell with the idea of taking the project to a new level by proposing Duncan Grant undertake a scheme at Berwick. For the first time a modern artist of national standing would undertake a complete decorative scheme for an historic rural church. If the project was successful, they believed it would stimulate demand for commissions in churches all over the country to alleviate the plight of many artists.’ (http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/Bishop%20Bell%20Anniversary%20Leaflet%20Web%20.pdf)

‘Duncan Grant (1885-1978) was the lead artist for the murals and put forward the initial proposals. He moved with Vanessa Bell (1879 – 1961) and her husband, Clive, to Charleston Farmhouse at the foot of the Downs, three miles to the west of Berwick Church, in 1916. Vanessa was sister of Virginia Woolf.

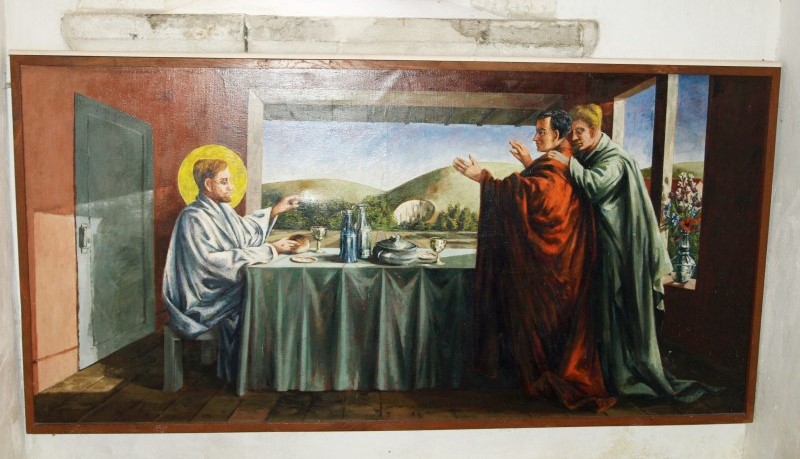

Quentin Bell (1910-1996) was the son of Vanessa and Clive Bell and undertook all the paintings within the Chancel as well as ‘The Supper at Emmaus’ at the end of the north aisle.’ They ‘had in view a ‘decorative scheme’ which, rather than simply being a series of individual paintings within frames, would create an environment with its own particular feeling and aesthetic.’ http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/the%20bloomsbury%20artists.html)

The six larger works are Christ in Glory and a crucifixion scene, The Victory of Calvary, by Duncan Grant; The Supper at Emmaus and The Wise and Foolish Virgins by Quentin Bell; and The Annunciation and The Nativity by Vanessa Bell.’ http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/Vanessa%20Bell's%20Bethlehem%20v.3%20for%20website.pdf)

Grant’s work was ‘influenced by his travels in Italy where, as an art student, he had seen the mosaics at Ravenna and copied the frescoes of Pierodella Francesca (1420-1492) at Arezzo. Then in Paris he had copied works by Chardin (1699-1779) portraying scenes from everyday life, ordinary people in work or recreation. At the same time he studied the work of the Impressionists and was later greatly influenced by the Post-Impressionists such as Cezanne, Seurat, and others …

Duncan Grant: Crucifixion

The murals at Berwick exhibit influences from all these traditions, but also something of the artists’ focus on the intimacy of the home and personal relationships and their love of the beauty and simplicity of the Downland landscape.’ (http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/the%20bloomsbury%20artists.html)

Duncan Grant: pulpit

Berwick Church was unusual in that ‘the plain leaded lights in its nave did not have figures or colour to clash with the paintings around them, and this was even more pronounced after bomb damage caused them to be replaced with completely plain glass. This gives beautiful views of the surrounding Sussex countryside, which seem to complement rather than compete with the paintings, many of which have the same countryside as their background.’ (http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/Vanessa%20Bell's%20Bethlehem%20v.3%20for%20website.pdf)

Quentin Bell: Supper at Emmaus

‘The Berwick commission required the agreement of both the local Parochial Church Council and also the Chancellor of the Diocese. He was himself advised by the Diocesan Advisory Committee (DAC) …

However, just before the Chancellor could give his authorisation, one member of the parish lodged a formal petition objecting to the murals. This triggered a 'Consistory Court' hearing at which evidence was heard from both those in favour and those opposed to the scheme. Bishop Bell along with members of the CIAD felt that much of the future of Church Patronage of the arts might rest upon this commission.

In the small flint schoolhouse, just down the lane from the church on 1st October 1941, the court heard evidence from Sir Kenneth Clark, Bertram Nicholls and Frederick Etchells in support of the scheme. The sincerity of the artists was emphasised along with their generosity in asking for only a fraction of what the work would normally cost. Despite the objections, the Chancellor authorised the commission to go ahead.’ (http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/Bishop%20Bell%20Anniversary%20Leaflet%20Web%20.pdf)

Duncan Grant: Autumn (one of the Four Seasons series)

It is difficult to measure the impact that Bishop Bell, and the Berwick murals in particular, have had on Church patronage of ‘modern art’. Grant was only to receive one other church commission – frescoes painted in 1959 for Lincoln Cathedral’s Russell Chantry – and the catalytic effect for which Bell had hoped did not materialise in any dramatic way. However, much commissioning did take place in the post-war years particularly where reconstruction to damaged churches was needed. The murals themselves looked back in terms of style to the grand ‘tradition of ecclesiastical art’ while their content was nostalgic for a past picture of rural England which was rapidly being lost. Both factors meant that the scheme at Berwick could not serve as a model for Church patronage of modern art as Bell had hoped. To visit Berwick today in the context of my wider sabbatical art pilgrimage makes clear that it is no more than a beautiful siding or cul-de-sac in the history of the revival of sacred art in the twentieth century.

Two exhibitions indicate the extent and the constraints of the approach pioneered by Bell and Hussey (which has significant synchronicity with that of Couturier and Régamy in France). Commission, at the Wallspace Gallery, demonstrated that an upsurge of commissioning from the church had seen many significant contemporary artists creating art for church spaces. As a result, it suggested that we are witnessing something of a renaissance of commissioned art for churches and cathedrals in the UK; a renaissance which began as a result of Bell and Hussey’s example and inspiration.

British Design 1948 - 2012 at the V&A began with work by artists such as Henry Moore, John Piper and Graham Sutherland who were key figures commissioned for major post-war projects such as the Festival of Britain, Harlow New Town and Coventry Cathedral. After this beginning where a close relationship between Church and art was demonstrated the only other significant reference to Christianity in the exhibition came with Damien Hirst’s Pharmacy wallpaper. Here prescription drugs are given Biblical labels suggesting that healthcare has become our contemporary religion. The use Hirst makes of Christian references in this work suggests that Christianity has been superceded, an impression also given by the absence of Christian references in the counter-cultural movements showcased in the exhibition later sections; from 1960s ‘Swinging London’, through to the 1970s punk scene to the emergence of ‘Cool Britannia’ in the 1990s. The exhibition implies that the Churchwas unable to engage in any significant manner with these subversive strands of work.

In this way, some limitations of the Bell/Hussey, Couturier/Regamy approach become apparent as the mainstream art movements of the day may not share a natural affinity with the Church (particularly when the Church is seen as a part of what is to be subverted) and, if the focus of the Church is on engaging key mainstream artists, then less attention may be paid to supporting emerging artists with a Christian faith able to engage effectively with the mainstream art world.

The artists at Berwick were considered ‘avant garde’ in their day but they actually produced a scheme for the church which drew heavily on the ‘tradition of ecclesiastical art. They paid ‘homage to the high points of the artistic heritage of a European Civilization’ which was, at that time, in turmoil. Though they were modern artists they expressed a respect for both the history and tradition of art and the simplicity of the setting and community for whom they were painting.’

.jpg)

Duncan Grant: Christ in Glory and Vanessa Bell: Annunciation

The murals are, like those of Stanley Spencer in the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere, ‘a unique example of war art’: ‘They record the landscape, the people, and the way of life that was under threat. Christ in Glory depicting, amongst the three servicemen shown, Douglas Hemming who was killed at Caen, takes on a war memorial role. Their religious content reflects the belief of their patron that Christianity was the central pillar of a European civilization that was under threat from the despotic forces of evil.’ As with Spencer’s murals, the artist’s love for and use of ‘local people and the local landscape showed how the divine was a part of the everyday’ enabling them to ‘sense the closeness of God to their own lives.’ As Bell put it in his dedication sermon: ‘The pictures will bring home to you the real truth of the Bible story ...help the pages of the New Testament to speak to you - not as sacred personages living in a far-off land and time, but as human beings ...with the same kind of human troubles, and faults, and goodness, and dangers, that we know in Sussex today.’ (http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/Bishop%20Bell%20Anniversary%20Leaflet%20Web%20.pdf)

***

St Michael and All Angels, Berwick: Berwick Village, BN26 6SR. Web: http://www.berwickchurch.org.uk/index.html.

Jonathan Evens is Associate Vicar for HeartEdge at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London. Through HeartEdge, a network of churches, he encourages congregations to engage with culture, compassion and commerce. He is co-author of ‘The Secret Chord,’ an impassioned study of the role of music in cultural life written through the prism of Christian belief. He writes regularly on the arts for a range of publications and blogs at https://joninbetween.blogspot.com/.