Gauguin, Paul - by Alan wilson

Reflecting on a Gauguin Masterpiece

by Alan Wilson

I am going to reflect on one key painting by that crazy old stockbroker who became the archetypical bohemian artist of the late 19th century, Paul Gauguin. My association with his art goes back a long way into my school days and then into student days at the Glasgow school of Art. I should say that my following reflections will mainly be that of an artist engaging with the painting, rather than as a theorist. The reason for this is obvious: painting is a visual language with its own unique vocabulary. I like what Neil MacGregor said about great pictures: they “speak from the heart to the heart, articulating the deepest feelings of those who look at them.” The word “look” is vital in his insight: these deep feelings are in response to what we see, not what we theorise. On saying that, one of my prized possessions is Hans Rookmaaker’s book on Gauguin and 19th Century Art Theory which has helped me immensely over the years when teaching about Post-Impressionism. The obtaining of the book has a story behind it.

I was converted at art school when going into my final year in the early 1980’s and was given a copy of Modern Art And The Death Of A Culture by a friend: it enabled me to navigate my way through the choppy waters of Modernism, placing it within a philosophical and religious context. I then discovered that Rookmaaker had published his dissertation on Gauguin back in 1959 and so I tried to seek out a copy; but for love or money I could not find it despite being an avid prowler of second-hand bookshops. This was the era without the internet or Amazon, so finding a rare book was like a gold prospector looking for that prize nugget!

Not long after leaving the art school I discovered another Christian writer engaging in cultural debate and he was a Scotsman with my own surname, John Wilson. In one of his books I saw in his bibliography Rookmaaker’s book on Gauguin. I cannot remember the details, but I managed to track him down and begged him for a loan of the book. We met up and became good friends and because he was much older than myself, I learned a lot from him, always picking his brains about poets, playwriters and philosophers (he really knew his Dooyeweerd!). He helped secure my first one-man show in Edinburgh and wrote to me a nice letter which really amounted to a review of my exhibition. In the letter he expressed a liking for a picture in the exhibition called Love Girl and the Innocent based on my reading of a Solzhenitsyn play. I instantly grasped the opportunity and said I would do a “swap” for the Rookmaaker book on Gauguin. John agreed and so we both handed over our bargaining items and that is how I came into possession of what I still think is the best treatise written on that egotistical but gifted painter and his artistic milieu. I had found my nugget of gold and repeatedly over the years I return to enjoy it.

My first encounter with Gauguin, however, goes back to a time before I acquired the Rookmaaker book. I was still at school and studying for my Higher Art, aged seventeen. I had literally gone nuts for Impressionism, my eyes gorging on all that vigorous brushwork that looked so spontaneous and yet never careless. The technical changes from what had gone before thrilled my painterly eye, especially the improvised brushwork leaving traces of irregular strokes of pure colour all juxtaposed to achieve an impression of rippling water, swaying trees and grass and moving clouds. This was spontaneous, on the spot painting (which I loved), and so what I found strange was reading that Manet and Degas maintained that their art was not spontaneous. I really felt that hard to believe. However, I soon realised through copying pictures like The Bar at the Folies Bergère and In the Rehearsal Room that they were compositionally planned in quite sophisticated ways. This was also true of Degas’ larger portraits. Photography and Japanese art (particularly prints) were informing how their art was composed in terms of the spatial arrangement in the design. There was literally more to Impressionist painting than meets the eye. Of course, generally it was all about the eye (did not Cézanne say that Monet was “only an eye?”) and was predominantly about that give and take between the movement of hand in response to what is immediately gazed upon by the artist. And because so many Impressionist paintings were “en plein air”, the mark-making was of necessity quick and flexible in order to pin down a fleeting moment in time. It was the degree of unfinish that infuriated so many critics at the time, but it was precisely this aspect of unfinish which I loved with all its evocative sketchiness. Even Cézanne, who would become a favourite, kept a freshness to his hatched staccato brush strokes and contour lines with all their shiftiness, despite his far slower build-up of the canvas surface.

Van Gogh’s surfaces were more frenzied, but not always: when I sketched examples of his actual work exhibited in Scotland’s Galleries, I noticed the strokes were never as wild as I imagined but were in fact considered and even decorative: the popular idea that his brushwork is always convulsive is simply not true. It was on a school trip to the Edinburgh National Gallery that my eye registered this contrast in painting methods in Van Gogh. His Olive Trees displayed the trademark turmoil of impasto rhythms over every inch of the surface, but the adjacent Orchard in Blossom had none of this frenzy. Clearly something else was at work here, a different type of conception. I had a strong hunch even as a teenager that Gauguin’s influence was having an effect along with his love of all things Japanese.

The Orchard was painted in 1888 after Gauguin had moved into the Yellow House with Vincent’s vision of it being a “House of Friends” for painters. That date is significant. Gauguin had turned up and they painted together as artistic brothers of the brush, but as we all know within months the camaraderie had all gone horribly awry, and Vincent in a bout of madness cut off the lobe of his ear after a terrible quarrel. The olive trees would be painted in the aftermath, in 1889, and so the same frantic strokes of thick paint resemble the turbulence in his menacing Crows Flying over a Cornfield painted months later. This famous picture of a cornfield had gripped my imagination since I was a ten-year-old after my Primary school teacher had returned from Holland with a poster of it and hung it in the classroom, so I was looking forward to seeing a painting from the same period. The Olive Trees did not disappoint, but the Orchard in Blossom made me realise that the influence of Gauguin’s ideas about painting were making Vincent artistically bi-polar!

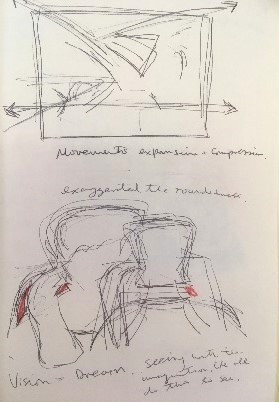

I had gone to the National Gallery that day with the full intention of feeding my Vincent and Cézanne mania. Gauguin had never really appealed to me. For one thing his drawing just seemed too clumsy and I believed real painting had to be about artistically realising “one’s sensations before nature” as Cézanne banged on about. Sure enough, when I got there I was besotted by Van Gogh’s Olive Trees, and the wonderful Degas’ portrait of Martelli was a revelation with its fascinating composition and superb draughtsmanship. Looking round that magnificent small room of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism my eye eventually landed on Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon and my first reaction was one of incredulity because it hung close to the Degas. “What a hack,” I was thinking. Standing looking at it my inner voice was saying, “This guy can’t paint, and he certainly can’t draw.” I was just about to dismiss it when my art teacher came over and told me it was one of the most significant paintings of the era and for what would follow in the twentieth century. With this as a prompt I decided to copy it, hoping it would reveal some of the secrets that merited it as a significant masterpiece of Post-Impressionism. I always copy in my sketchbook to help me understand. I had been copying paintings from art books since I was about ten because it is the only way for me to see and understand what is happening. What was happening in this Gauguin painting that my eye had initially mistrusted? What had I failed to recognise?

I started to sketch The Vision and made umpteen transcriptions (over the years with my many visits I still copy it), because I wanted to fathom the differences to the other Impressionist paintings in the room including Gauguin’s own Martinique Landscape that hung immediately beside it and which almost acted as a foil, to highlight the sudden contrast that emerged in his style. Unlike the Sermon, the Martinique Landscape simply dazzled with its mosaic-like surface of staccato chisel-head strokes, that juxtaposed reddish pinks with a myriad of greens and blues. It was not quite the systematic Neo-Impressionism of Seurat’s divisionism or the lyrical structuralism of Cézanne, but somewhere in between. What it did have in relation to these two artists was the slow patient build-up of very distinctive brush marks. Despite me seeing its stylistic relation to Cézanne, I was starting to feel that this Martinique landscape was not fully an “en plein air” construction but more of a reconstruction; an “after image” painted as much from memory in the studio as from on the spot. My guess was at the time, and so remains, that it was started directly “before” nature and then finished later on “after” the immediate experience. Did this mixture of making a painting “before” and “after” prompt a sense of conflict in Gauguin; a sense of one compromising with Impressionism? I think it did. It is important to understand this is such a huge decision especially for a landscape painter – to either work directly from nature or to work from memory and even the imagination. The process of both methods is so different, as any painter can tell you. It is as if you must commit to one or the other to produce an image of authenticity.

The Vision after the Sermon is where we see Gauguin fully commit to the latter. There will be no more compromise. This is where his philosophy of “dreaming before nature” turns his art into a more decorative and symbolic activity in what would become known as Synthetist art, where mood and content would be distilled into a distinctive abstraction. Emil Bernard was in Port-Aven at the time, sharing his art theories of a symbolic language inspired by medieval and local devotional folk art. Although I had not at that point read about such things, my sketches were nevertheless telling me that he was escaping from what he called the “shackles of verisimilitude” and aiming for what Rookmaaker described as the “iconic”. Gauguin instinctively felt that reality included more than the eye physically registers and so this painting really is a pictorial manifesto against the “abomination of naturalism” (realism and impressionism) and his own reconnection to spiritual feeling, all expressed through a shocking use of colour and simplification of form.

.jpg)

For this radical artist who was a “back to nature” and the “noble savage” proponent it is hard to tell if there was a genuine sincerity in his church attendance at the time, especially since he said so many disparaging things about the Christian faith. It is more likely he was just fascinated by the idea of faith and naïve religion as a part of reality. That type of attitude was rife during the second half of the nineteenth century and possibly found its greatest expression in the two massive volumes of The Golden Bough by James George Fraser published in 1890. We also know that Joseph Peladan was trying to create a cult of mystical esoteric religion and that Gauguin was even involved with his circle of fellow thinkers. The Enlightenment’s Romantic thinker, Johan Gottfried Herder, had a generation earlier felt civilization should find its heritage and ground itself in folk culture. In that mindset Gauguin wrote to Vincent telling him the figures in the painting were “rustic and superstitious”. This anthropological fascination with primal religious experience and his radical, primitive aesthetic are what would make the painting a milestone in art history.

.jpg)

From my sketches I certainly learned a lot about the change of direction from impressionistic naturalism towards an increased emphasis on the “iconic”. What was obvious to me was the self-conscious organisation of the shapes and colours to increase the flatness of the surface. These simple flat shapes were given more impact by the greater emphasis Gauguin now put on the contours. Because the contours are given emphasis, the rhythms of curves and counter curves are felt more, making the painting strangely expand and contract at the same time! The curved apple tree cuts diagonally across the composition in a dramatic way and divides the layout with two strong red negative shapes where Jacob and the angel wrestle on the right side and a cow is crudely rendered in the left. Red being the opposite of green speaks of a visionary reality as opposed to a natural one, and the fact that Gauguin contrasts it with green in the foliage and Jacob’s clothes symbolically suggests the whole idea of struggle. He deliberately orchestrates these complementary colours to achieve a decorativeness and expressiveness at the same time. Decorative would never be merely an aesthetic issue for him: it was tied to the meaning. That is what the iconic is about. Red suggests fire and the Holy Spirit, and this scene is about the reality of the spiritual. It is all an incredible balancing act. The colours wrestle to emphasise the theme (something Munch would do), but due to their flatness they also achieve a highly decorative surface not unlike a Japanese print by his contemporary Kunichika. Unlike a Japanese woodcut print however, the flatness has a coarse texture because the paint has been slowly applied with no medium upon Burlap rather than fine canvas. And when you look closely you can see a green ground beneath, which only enriches the top layer of red. It is all very rough in technique; perhaps the roughest painting he ever produced.

However, the imagery is not rough at all but symbolically carefully considered. The key image is not really Jacob and the angel but the central peasant woman who looks up and is transfixed by the battling figures. Gauguin has strategically placed her eye exactly in the middle of the canvas like a target bullseye. Being central to the layout (and because all the other women have their eyes shut in prayer) the open eye speaks of “vision” born from her devotion and so relates to the title. I feel there is an intended connection between her open gaze and the peasant woman immediately behind her whose profile is downward with her eyes closed. This humble gesture along with the care Gauguin has given to rendering her praying hands conveys the reality of genuine faith and piety. The eye of faith is being symbolised here by Gauguin, in fact admired by him, even though I very much doubt he shared that faith. As he said, it is “superstition” and yet he wants to celebrate the sincerity of devout faith as part of the human condition.

The fact that Gauguin tried to sell the painting to the church demonstrates how he must have equated what he was doing with medieval altarpieces. However, rather than wealthy patrons being included as was so often the case, he depicts only these ordinary Breton Women who are immediately identified by their peasant costume, particularly their white coiffes which dominate so much of the scene. Symbolically and literally they emphasise that these are not modern bourgeois women of Paris. I feel he has given the coiffes a very minimum amount of modulation to emphasise their whiteness which always suggests purity, and the two large coiffes have an almost dove-like suggestion to them: or white seagulls! Formally they all create a counter-curving movement to that of the tree and lead your eye up and round the left edge highlighting the kneeling women. They look as if they are still in church praying and have been cropped and montaged upon the red visionary field with its tree of life. The fact that the angel has been given golden wings makes me think the sermon alluded to the pre-incarnate Christ as the angel of God.

These are clearly women unaffected by the rationalist explaining away of the faith by Higher Critics during the 19th century. Gauguin no doubt saw their religion as primitive, but he depicts it as honest faith and that is why he shows us “their” vision taking place in their minds eye. As I have maintained, the red field symbolically tells us that Jacob and the angel are being seen spiritually and not literally, but they are nevertheless just as real to these simple believers as the cow in the field. I am sure that is why Gauguin rendered the struggling patriarch and angel in the same manner as the women and the cow. Just look at the feet. They may be simply drawn, but they are “real” feet, firmly planted on the ground. Even though he sees it as superstition, Gauguin is saying that these Christian believers are not relating to this sermon as myth but as actual reality and history. Jacob was real. The angel was real, and they did wrestle just as the scriptures proclaim. That makes it a distinctly Christian painting to me. Artists can be implicitly Christian or explicitly Christian in their work. The great irony with this visual testimony is that Gauguin never shared the faith he saw in these women, even though he makes an appearance in the bottom corner with his head down! I think H W Janson was right when he said Gauguin “could paint pictures about faith, but not from faith”, particularly the Christian faith.

**

Paul Gauguin: Vision after the Sermon, 1888, Oil on canvas, 72.2 cm × 91 cm (28.4 in × 35.8 in). Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh.

Alan Wilson studied at the Glasgow School of Art between 1979-1983. He has been the Head of Art at Hamilton College for 35 years and will retire in 2021. He has exhibited regularly, also with his friend Peter Howson, a famous Scottish artist with an international reputation. He is married to Angela and has two grown-up children and two grandchildren.