Evergood, Philip - VM - Victoria Emily Jones

Philip Evergood: The New Lazarus

Waking Up from Apathy

by Victoria Emily Jones

An American social realist painter active during the Great Depression, World War II, and the postwar era, Philip Evergood was a firm believer in art’s ability to bring about social change. He spent most of his career as an unabashed “protest artist,” condemning war, racism, xenophobia, economic inequality, and labor exploitation, and advocating for a better way.

Among his papers in the Archives of American Art (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC) is a hand-copied quote by Canadian Norman Bethune, a battlefield surgeon during the Spanish Civil War and an amateur artist: “The function of the artist is to disturb. His duty is to arouse the sleepers, to shake the complacent pillars of the world. He reminds the world of its dark ancestry, shows the world its present, and points the way to its new birth.” [1]

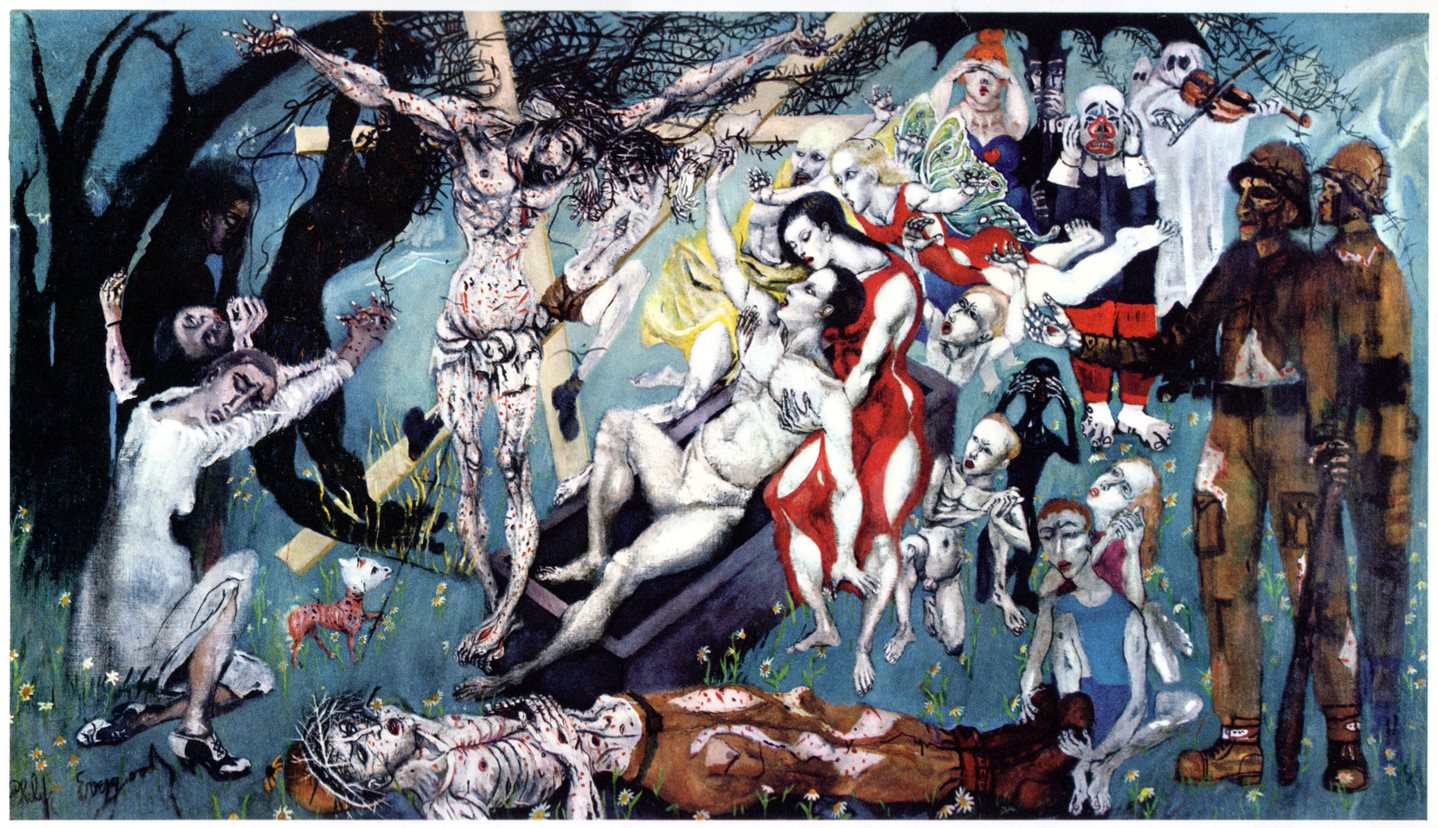

Evergood’s The New Lazarus demonstrates this aim. What started out in 1927 as a straightforward interpretation of the John 11 narrative of Jesus raising a dead man to life evolved over the course of three decades—Evergood completed the painting in 1954—into an elaborate allegory of humanity rising into action against the modern forces of evil.

Like many twentieth-century artists, Evergood uses the Crucifixion as a symbol of human suffering and depravity—we both feel deep pain and inflict it on others. “I use the Christ symbol, the image of Christ crucified and thorn-pierced as did Grünewald who inspired me, to say that man is inhuman to man and why can’t he change?” [2] The New Lazarus shares with the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516) a grotesque, battered corpus, but Evergood replaces the closed eyes of Matthias Grünewald’s Jesus with a confrontational gaze directed straight at the viewer, as if Christ is saying, “Look what you’ve done.” The flayed lamb with a flaming cross at Jesus’s feet also references Grünewald, a disturbing twist on the Agnus Dei.

Flanking Jesus are not the two guilty thieves mentioned in the Gospels but rather two other innocents, also crucified and crowned with a nest of thorns and barbed wire. At Jesus’s right a lynched black man hangs from a tree, mourned by his mother, while across the way a white-hooded Ku Klux Klansman plays the fiddle as part of the entertainment.

At Jesus’s left a young soldier is splayed out on his own cross, sacrificed by his country’s war machine. One of the soldier’s compatriots lies dead in the foreground, bearing stigmata, his two younger siblings crying out at his booted feet. Zombie-like, two soldiers with cavernous eyes approach from the right, one of them gesturing toward the wider scene with wounded hand, beckoning us to behold the horrors.

In the background a trio of “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” figures symbolize the willful ignorance and lack of moral responsibility of those in power. The umbrella evokes Neville Chamberlain, a former British prime minister known for his failed policy of appeasement in dealing with Hitler. After he signed the Munich Agreement in 1938, his trademark accessory came to symbolize, in cartoons and protests, political weakness. The well-dressed man and woman under the umbrella, who cover their mouth and eyes, may also be an indictment of the uneven distribution of wealth—notice the two naked, starving children cowering at the corner of Lazarus’s coffin.

Also under the umbrella is a clown who plugs his ears. This comic group recalls the prophetic passages of scripture where God condemns his people as “foolish and senseless . . . , who have eyes, but see not, who have ears, but hear not” (Jer. 5:21; cf. Ezek. 12:1–2), as well as Jesus’ words in Matthew 13:15: “This people’s heart has grown dull, and with their ears they can barely hear, and their eyes they have closed . . .”

Amid the sin and chaos, a centrally located Lazarus rises from his grave, supported by a woman who may be his sister Mary. His gaping mouth registers shock at the miseries that surround him—or perhaps he is stunned by a vision of a bright future that exists somewhere outside the frame. Blossoming flowers suggest hope.

Evergood was a humanist. He believed good and evil forces fight each other in the universe and inside every individual, and that humans are the deciding factor in this cosmic battle; we must redirect our energies toward the good and only then achieve a better world. Christ was decentered in Evergood’s philosophy, as in this painting, and Lazarus takes his place as the means of redemption. For Evergood, Lazarus represents the new person of courage dedicated to peace and justice. The New Lazarus is a wake-up call.

As a Christian I believe in the necessity of the Holy Spirit’s regenerative work. But that doesn’t diminish anyone’s responsibility for helping to build a world where all can flourish. My gaze turns again to meet Christ’s, and I wonder if he’s issuing not so much an accusation as a challenge: Will you be reborn into a radical love of God and neighbor? His tearful appeal at Bethany echoes down through the ages into the tombs of our own making: “Lazarus, come forth.”

*******

Philip Evergood: The New Lazarus, 1927–54, oil and enamel on canvas, mounted on wood, 58 1/4 × 93 3/8 in. (148 × 237.2 cm), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, USA. https://whitney.org/collection/works/686

Philip Evergood (1901–1973) was born in New York City to a father of Polish Jewish descent and a Cornish Irish mother. He attended boarding schools in England and was a student at Eton during the German air raids of 1914–1918. During the 1920s he studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and traveled in Europe, returning to America for good in 1931 to study with George Luks of the Ashcan School, an art movement that sought to depict the daily realities of urban life in New York City. Evergood participated in and used his art to document the struggles of workers, minorities, and the poor, and he was an active member of progressive artists’ organizations, such as the Artists Union, while working in federally sponsored artists’ relief programs. He was deeply inspired by the socially engaged art of the Mexican muralists and completed several mural projects of his own. Many of his paintings weave together sensuousness, symbolism, fantasy, humor, satire, and social comment, using garish colors and expressionist distortion of form, with stylistic influences including El Greco, Bosch, Bruegel, Goya, Daumier, and Toulouse-Lautrec. He was also a printmaker and a sculptor.

Victoria Emily Jones lives in the Baltimore area of the United States, where she works as an editorial freelancer and blogs at ArtandTheology.org. Her educational background is in journalism, English literature, and music, and her current research focuses on ways in which the arts can stimulate renewed theological engagement with the Bible. She serves on the board of the Eliot Society, a faith-based arts nonprofit, and is a contributor to the Visual Commentary on Scripture, an initiative of King’s College London, UK.

NOTES

1. Evergood Papers, roll 1354, frames 1175–76; quoted in Patricia Hills, “Art and Politics in the Popular Front: The Union Work and Social Realism of Philip Evergood,” in The Social and the Real: Political Art of the 1930s in the Western Hemisphere, ed. Alejandro Anreus, Diana Linden, and Jonathan Weinberg (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2006), 181.

2. Philip Evergood, from a letter written in 1966; quoted in Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1987), 167.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 30 August 2020