Good Friday through Easter - Sassandra: Ecce Homo

Sassandra: Ecce Homo

See the Man Who Triumphed

by Isabelle Letienne-Olekhnovitch

When one considers any work of art, it is good to be silent at first. And this is even truer when one considers a work dealing with the death of Christ. The death of a man, the death of the Man, can leave no one indifferent.

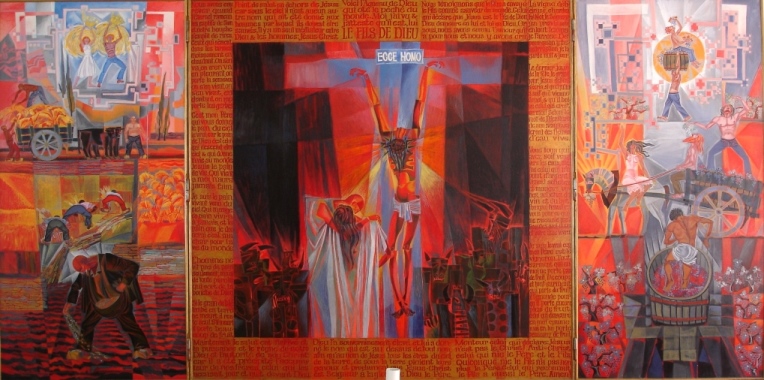

The triptych-form chosen by Sassandra is of utmost importance. First it indicates a rigorous, forceful composition. It also implies a procedure to follow for anyone who wants to understand the painting, a voyage for the eye, an itinerary from closing to opening, even to unfurling, because – once the triptych has been opened and studied – there are two other, separate panels to contemplate: the triptych is actually a polyptych.

The whole work stretches to 6.4 m. It is made up of five wooden panels on which the artist glued pieces of cut-up paper, meant to give depth to certain parts and certain details, before applying the colours.

This is the itinerary. Closed, the triptych offers us a picture of the Fall. The eye is struck by the blackness, symbol of the forces of evil. A man and a woman sit with their backs to each other: communication is broken. Adam holds his head in his hands, Eve looks at her body; she seems already to be suffering from the pain of childbirth. The man below gives himself to the labour of ploughing, to the sweat of his brow, and a child is born into a cradle of thorns. Yet in this suffering one reads the hope of redemption through the birth of a redeemer and the sun rising before the ploughman.

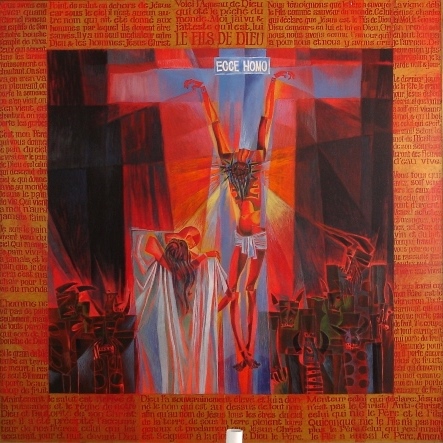

The panels open, the eye is assaulted by a flood of black and red and seeks a place of quiet, away from the bulls of Bashan (Ps. 22). In the heart of the central panel it finds it, where the sides of a double door seem to open and the sky appears bright azure. And here – a stroke of genius on the part of Sassandra – the paradox of the Christian faith is expressed: this blue is the colour of the wood of the cross, the place of suffering where Christ paid for our peace, the place of peace.

He is dead. It is finished. His head is bowed, heavily bowed down, as though dragged downwards by the weight of sin, inexorably. The weight of sin. The weight of death.

At the left of the cross stands a couple, also with bowed head. Anyone familiar with the iconography of the crucifixion, anyone who has read the Gospel of John, thinks he recognizes the apostle and Mary. But there is ambiguity. The artist points out that he rather thought of the first human couple. Here the man and the woman no longer have their backs to each other, as the death of Christ has brought about their reconciliation.

Against a golden background, all around the central scene, Sassandra has painted Bible verses in characters large enough to be read but small enough not to attack the eye. One can take a close look and receive the sacred text. The artist wanted only four words to immediately catch the eye: LE FILS DE DIEU [the Son of God]. They have been purposely placed high up, above the cross, above the inscription the artist took care to place in white letters against an azure background: ECCE HOMO – this is the man, man and God, true man and true God. This central affirmation allows us to understand the redemptive value of Christ’s sacrifice.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

In the side panels on the left and right two scenes meet our gaze, or rather two groups of scenes, for the painting displays all the stages of the work of producing wheat and wine. We might be tempted to describe these as secular, but the work of the farmer and winegrower is under God’s eye, in God’s creation. Even less can we call them secular, when we see that in both these scenes hardship is changed into joy. “Those who sow in tears will reap with songs of joy” (Ps. 126:5). The sun has risen. God’s penalty has been reversed. And do these panels not also recall the Lord’s Supper, the broken bread, the wine poured out, which Christians partake in together as a sign that they belong to the crucified One?

|

|

In the side panels on the left and right two scenes meet our gaze, or rather two groups of scenes, for the painting displays all the stages of the work of producing wheat and wine. We might be tempted to describe these as secular, but the work of the farmer and winegrower is under God’s eye, in God’s creation. Even less can we call them secular, when we see that in both these scenes hardship is changed into joy. “Those who sow in tears will reap with songs of joy” (Ps. 126:5). The sun has risen. God’s penalty has been reversed. And do these panels not also recall the Lord’s Supper, the broken bread, the wine poured out, which Christians partake in together as a sign that they belong to the crucified One?

When we take a step back, we become aware of two separate panels to the left and the right of the triptych. They make clear that Christ is not a mythical character, but that he is rooted in history, in the human family of Jesse. Three characters in this vertical gallery of Jesus’ ancestors appear: David fighting Goliath, Salomon on his throne, and Zorobabel with his architectural tools. Four circles depict the four elements, signifying God’s sovereignty over the universe, Christ’s involvement in creation.

Jesse (at the bottom of the left panel) points to the One who gives meaning to this long line of delivery: the Son of God, the son of Mary, the son of David. The artist has painted him standing calmly upon a raging sea, metaphor of the Christian life.

The crucified One is also the risen One, who is portrayed in the last panel. It is technically difficult to depict passing from darkness to light and still maintain the unity of the work. Here the darkness of death is progressively overcome as light penetrates it like an archipelago drifting toward the luminous circle radiating around Christ.

One must again keep quiet and let the painting, the colours and the forms speak. I put down my pen and look.

*******

Sassandra, Ecce Homo, 1977-1980, acrylic on paper, 200 x 640 cm. Vaux-sur-Seine, France.

Jacques Richard (“Sassandra” is his artist name) was born in 1932 to a missionary family in Sassandra, Ivory Coast, where he spent his youth. Upon returning to France, he studied graphic arts, lithography and the drawing of letters, after which he studied theology for three years. He finally decided to take the competitive examination in order to become an art teacher in Parisian public schools. Successful in this, he taught in several secondary institutions until he retired, all the while giving himself to drawing, painting and xylography and striving to deepen his thinking on art. As a favourite activity on the side he writes stories and poems. http://galeriesassandra.fr

Isabelle Letienne-Olekhnovitch was trained in classical literature and taught French, Greek and Latin for nine years in French secondary schools. She also taught Biblical Greek for many years at the Faculté Libre de Théologie Evangélique (Vaux-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris) and continues to do so by correspondence. Her writings include two historical novels on Protestantism in the area of Orléans and several devotional books. Married to Luc Olekhnovitch, ethicist and pastor of a Free Evangelical Church, she has always actively supported his ministry.

This meditation was translated by Janet Johnson.

ArtWay Visual Meditation February 19, 2017