‘God’s Little Artist’

Gwen John arrived in Paris in 1904, becoming a model for and lover of Auguste Rodin, then the most famous sculptor in the world with grand studios in central Paris. His home was located on the city’s southwestern outskirts, in the village of Meudon. At Rodin’s studio she also met the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who worked for a time as his assistant, and they became friends. The art show Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris, which will run until 8 October 2023 at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, West Sussex, UK, traces her 40-year career chronologically in relation to the two cities where she chose to live and work.

In 1911 she was able to move to Meudon herself, but kept her room in central Paris, travelling to work there daily, whilst also exhibiting, meeting friends, and visiting galleries. Her new life was made possible by a patron, the American collector of modernism, John Quinn. He paid her regularly and ensured she was included in the International Exhibition of Modern Art, the 1913 Armory Show in New York.

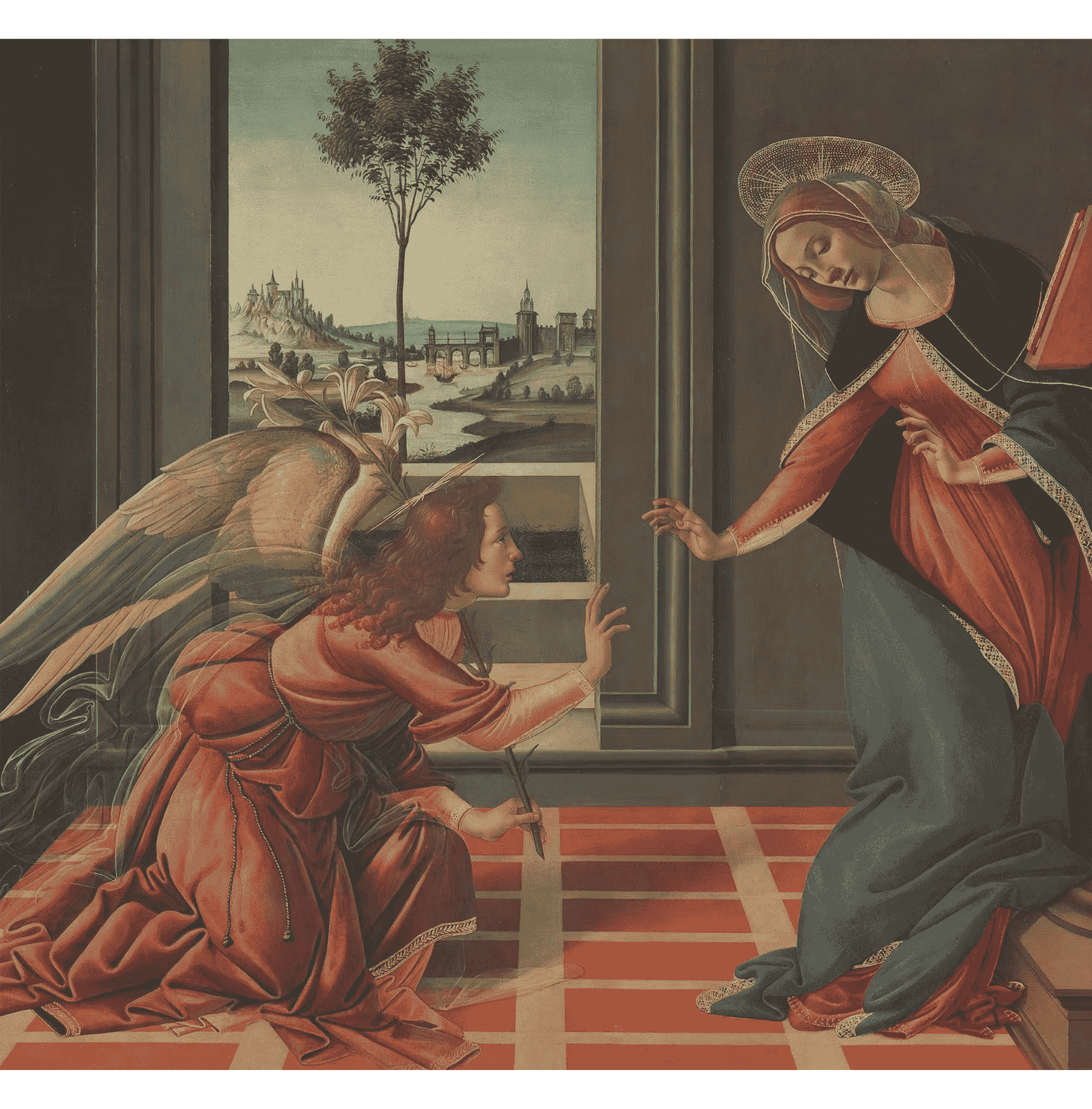

In 1913, she converted to Catholicism. The French Catholic Revival (roughly 1860 – 1960) was underway with figures such as Paul Claudel, Charles Péguy, Léon Bloy, Maurice Denis and Jacques Maritain being of influence. She admired the work of Georges Rouault, the pre-eminent Roman Catholic artist of his time, and Paul Cézanne, who sought to explore the eternal element of the Universe, the “Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus”. Maritain was a neighbour of John and she visited his home making a number of portrait drawings of Maritain and becoming enraptured by his sister-in-law, Ukrainian-born Véra Oumançoff. Her friend Rilke also remained an influence as he sought in his writings “to restore spirit to Western materialism” and encourage “a heightened awareness of how to live with the world as it is, of how to retain a sense of transcendence within a world of collapsed spiritual certainty.”

John wrote of herself as being “God's little artist” and of entering “into art as one enters into religion”. She wrote of God as “a God of quietness” and viewed every moment as holy and not to be soiled. This sense was expressed in the attention that she paid both to the subjects of her slowly evolving oil paintings, which have a stillness that is harmonious and ordered, and in the rapid sketches she made of local people in church. These seem, for her, to have been equated with prayer. She viewed herself as a sensual creature unable to pray for any length of time but inspired by the 'Little Way' of Saint Therese of Lisieux, which outlines how the smallest thing can be done in the name of God. John wrote that she must be a saint in her work. What she could express in her work, she wrote, was the “desire for a more interior life”. Accordingly, her art meditates quietly on the beauty of everyday existence in ways that set her work alongside that of artists such as Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin, Giorgio Morandi and Vilhelm Hammershøi.

Influenced by Cézanne, she painted multiple series of the same image with minute differences affecting the tone and atmosphere created. Despite the disapproval of the Meudon priest, she made a series of small gouache and watercolour drawings of worshippers. These are reminiscent of the work of Maurice Denis, with simplified dark lines filled with flat areas of colour. Works from this period also have a patchy appearance of the surface, influenced by what Denis termed ‘the mystique of the unfinished’ in Cézanne’s work and flat heavy outlines, perhaps in emulation of the work of Georges Rouault.

The local Meudon order of Dominican nuns, who prepared John for conversion, commissioned her to paint their founder Mère Marie Poussepin. John only had a small black and white prayer card of 1911 as source material, but transformed this small, printed monochrome image into a series of portraits with radiant presence, full of life and power. She felt that these portraits were a breakthrough in her art, perhaps because she had relied on her imagination and hard-won technique rather than the presence of a sitter. The art historian and later Tate director, John Rothenstein, believed these to be the very best of her paintings. One of them was bought from the convent by Quinn, who described it as “a beautiful jewel”. He compared his version positively to the paintings by Picasso he had just bought. In 1922, Quinn’s Mère Poussepin was shown in the exhibition ‘Seven English Modernists’ at The Sculptor’s Gallery in New York.

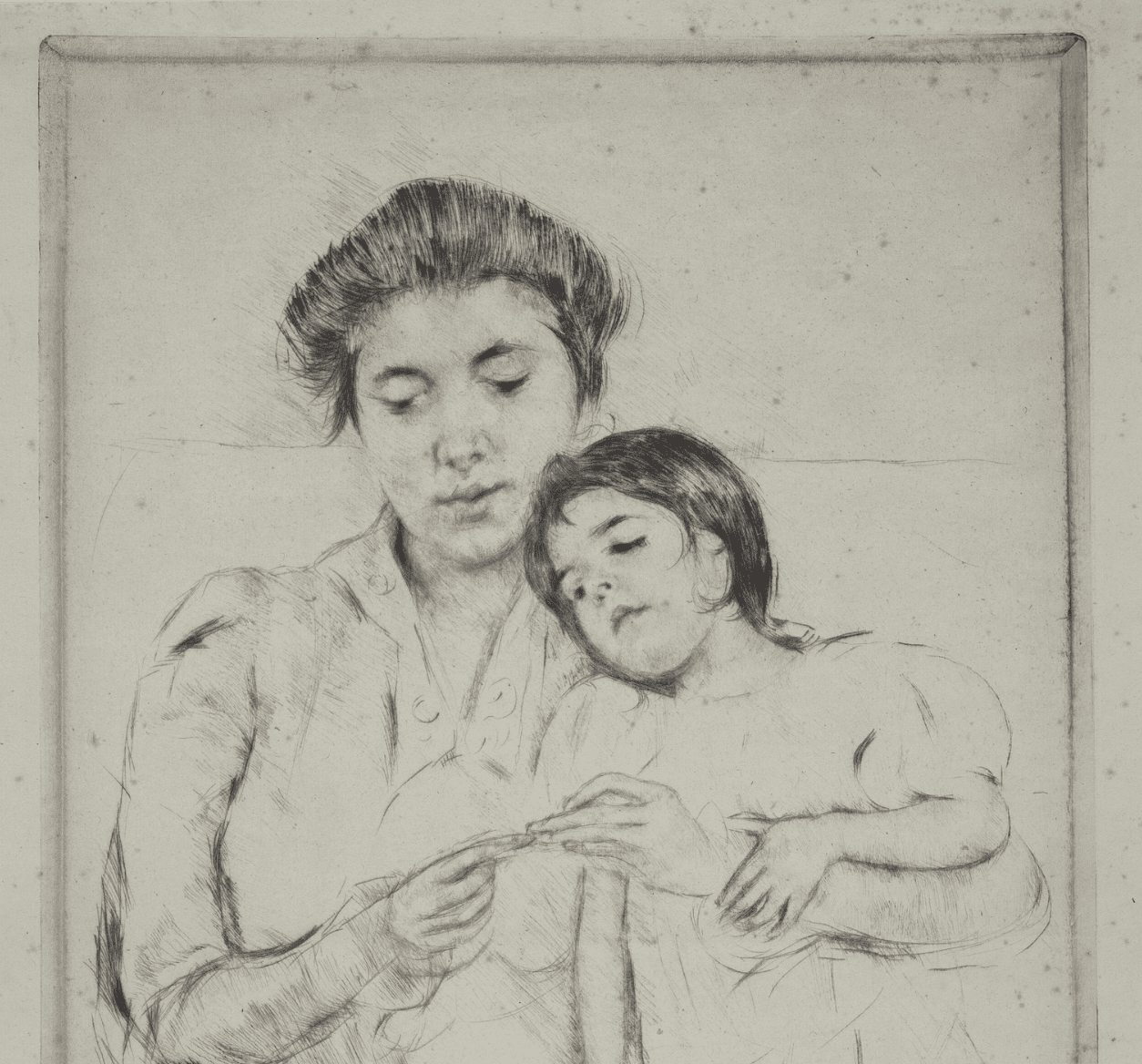

John also painted portraits of several nuns from the Convent, including a young woman (see image featured above), who may have been named Soeur (Sister) Marie-Céline. There are eight paintings of this nun, who was posed by John in the same way as Mere Poussepin appears in the prayer card. While the pose and clothing signal conformity, the attention John pays to her sitter reveals individuality and human presence.

Sir William Rothenstein, painter and printmaker, commented on these paintings, saying that John had given her “cool nuns with their quiet and beautiful hands ... the wisdom of quietude and purity.” The wisdom of quietude and purity which derives from paying prayerful attention is what we find expressed throughout John’s work and is the great gift that she offers to us.

**********

Gwen John, The Nun, c.1915-21, Oil on board. © Tate: Purchased 1940.

Gwen John, A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris, c.1907-9. Oil on canvas. © Sheffield Museums Trust.

Gwen John (1876–1939) was born in Haverfordwest, Wales. She lived and worked in the most exciting times and places in the story of European art, in London in the 1890s and in Paris in the first decade of the 20th century. Her work was sought after, and by the 1920s she was so admired in Paris that the American poet Jeanne Robert Foster wrote, “everyone knows of Miss John … and the Salon takes all she will send them.” Yet, [she] has often been misrepresented as a recluse, with little connection to the world around her. Independence, and at times, solitude, were important to her, but her archive also reveals a sociable artist, enjoying life in the art world amongst the great figures of her time. Her’s is … the story of a woman who was part of the culture of her age and was certain she would find a place within history – “I cannot imagine why my vision will have some value in the world - and yet I know it will.” (Room Guide - Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris)

Jonathan Evens is Team Rector for Wickford and Runwell in Essex, UK. Previously Associate Vicar for HeartEdge at St Martin-in-the-Fields in London, he was involved in developing HeartEdge as an international and ecumenical network of churches engaging congregations with culture, compassion and commerce. In that time, he also developed a range of arts initiatives at St Martin’s and St Stephen Walbrook, a church in the City of London where he was Priest-in-charge for three years. Jonathan is co-author of ‘The Secret Chord,’ an impassioned study of the role of music in cultural life written through the prism of Christian belief, and writes regularly on the visual arts for national arts and church media including Artlyst, ArtWay and Church Times. He also blogs regularly at https://joninbetween.blogspot.com/.

ArtWay Visual Meditation 30 July 2023

%20(1).png)